In the past few years, proposals for new industrial projects in Montezuma County have stirred up a storm of protests.

• In July, neighbors objected vociferously to Empire Electric’s plan to create a two-lot industrial planned unit development on 43 acres at Highway 491 and Road L. The county commissioners did grant the request for industrial zoning [Free Press, Aug. 2009].

• In June, the commissioners, voting 2-1, rejected a hugely controversial proposal for a treatment facility for energy-production wastes in the remote western part of the county. The developer has sued over the turndown. [Free Press, June 2009]

• Every proposal for permits for gravel and asphalt operations in the Mancos Valley has met with stiff resistance since 2007, when an especially odiferous hot-mix plant angered residents there.

• And a dispute over the placement of a 20,000-gallon propane-storage tank in a four-lot residential subdivision near Highway 184 in 2008 was so bitter that the county had sheriff’s deputies at a public hearing on the subject. [Free Press, January 2009] That proposal was eventually scrapped.

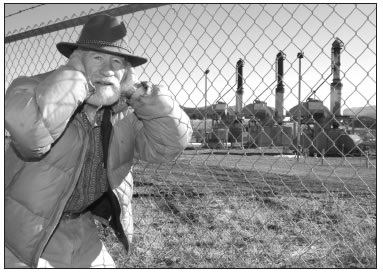

Ned Harper of Summit Ridge stands next to a natural-gas compressor station that neighbors say is obnoxiously loud. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

“It seems every time something comes along that would help the economy, we have a loud outcry,” said Commissioner Steve Chappell at a public hearing Jan. 12 for the first proposed asphalt operation in the Mancos Valley since the controversial one in 2007. “I think we have to be careful about destroying the economy and making this just somebody’s playground or retirement area.”

Chappell’s comments reflected the sentiments of many of the traditional residents in the county — that newcomers to the area (frequently wealthy retirees) complain about anything that might bring much-needed jobs and tax revenues.

But the situation is not so simple. People who have lived or are living near industrial uses tell a different story. While there are many cases where industry and homeowners can co-exist happily — and where industry even helps landowners by providing extra income to people with pipelines or gas wells on their property — industrial and residential uses are not always a good mix.

The problem, say people who have experienced some of the down side of living near major projects, is twofold: First, the most obnoxious impacts of some projects are often borne by people who see few if any of the financial benefits.

And second, when an operation does something that brings it out of compliance with rules and regulations, it can take months or years for neighbors to get their complaint heard by the appropriate agencies and to receive any relief.

The case of the asphalt plant was a perfect example.

Oh, that smell

Back in the summer of 2007, a number of Mancos Valley residents endured the impacts of a nearby industrial use when the Sky Ute Sand and Gravel Company and its sub-contractor, Kirtland, began making asphalt for a federal paving project for Mesa Verde National Park. Patricia Burk, who lives adjacent to the Noland gravel pit where the asphalt was being made, was among those affected the most.

“They would start these furnaces about 6:30 in the morning,” Burk said. “Then there would be 20 hours of this awful black stuff.”

Burk’s family has owned her property since 1949, when she and her parents first moved there. Burk left home, but moved back in 2001 with her husband. When Highway 160 was built decades ago, it split the tract in two. She now owns 10 acres on the north side of the highway and another 9 acres of the original homestead on the south side, plus more land they bought to the east.

The entrance to the Noland pit lies a few hundred yards to the east of her, with two other gravel pits (Stone and Four Corners Materials) to the east of Noland. “We have an industrial-commercial complex in these few miles along Highway 160,” Burk said.

Truck traffic, noise and dust were also concerns in 2007, but it was the smell that was intolerable, she said. The fumes were foul, by all accounts. The company was making a special type of asphalt required by the federal government for the national park. However, other operators, including officials with Ledcor CMI Inc., which plans a new asphalt project at the Noland pit next summer, have said there was no reason for the fumes to smell so bad and that the other operator was not doing the job right.

The last week in August of 2007 was the worst, according to Burk. “Our house was enveloped in asphalt fumes. You cannot believe what it looked like. Our house, our cattle, the cattle to the south of us — we were just blanketed in asphalt. We raise grass-fed cows and they don’t eat asphalt very well.”

Mary Jane Gosselin and her husband, Toma, moved to the Mancos Valley three years ago as a place to retire, purchasing seven acres on the south side of the highway. “We bought it because of the atmosphere, the cows, the views,” she said. “I was aware there was a gravel pit across the highway but you couldn’t see it.”

But they became well aware of its proximity in summer 2007. “We couldn’t open our window at night and we didn’t have any other cooling in our house,” Gosselin said. “We couldn’t plan a picnic in our yard because you never knew when the bad smells would show up. It made it very difficult to enjoy our own property.”

Seeking a remedy

Initially, neighbors tried to work things out. Gosselin was one of the first people to contact Sky Ute officials. “They said they’d be perfectly willing to work with us and they’d remedy the smells, but it didn’t happen.”

Burk agreed. “We didn’t realize if we wanted something done we had to do everything ourselves,” she said. “We had to get in touch with every agency and file complaints. That’s a very laborious thing for a citizenry to do. We learned these agencies weren’t caretaking our concerns. The EPA didn’t do anything to help us.”

Frustrated citizens finally brought the matter to the county’s attention, but relief was slow in coming. The planning department finally decided that although the Noland gravel pit had been in existence since before the land-use code was adopted, the asphalt operation was something new and therefore required a permit, which the companies had not sought.

“Weeks went by, while the companies were still spewing their crud into our world,” Burk said.

So, having found no help from federal or state agencies, the citizens pressed the county to stop a project that was being run under a contract with the federal government. And the county did shut down the asphalt operation, although by then the project was essentially over.

“Nothing happened and nobody helped us until we went to the commissioners,” Gosselin said. “They shut them down but it was three days before the project was due to end anyway. We lost that entire summer in terms of going outside and enjoying ourselves.”

The Noland family, owners of the pit, sued the county over the shutdown, claiming they did not need a high-impact permit, but the county prevailed in district court.

Making noise

Industry of a completely different type has affected a number of people living on Summit Ridge in the vicinity of a natural-gas compressor station called the Dolores Pumping Station. The compressor is run by Enterprise Products, which recently merged with Teppco Partners LP to create the largest publicly traded energy partnership in the country, according to the company’s web site.

The station is one of many compressors along a Mid-America Pipeline Company (MAPCO) pipeline that runs from Wyoming through Utah, Colorado and New Mexico. The main problem with the compressor station, neighbors say, is the noise.

“You can’t even see the place from where I live, yet it roars all night long,” said John Whitaker, who lives nearly a mile away. “We notice it mostly in the summer at night. There’s a constant roar. It sounds like a jet engine going over, all night long.”

Whitaker, who owns a company that does custom coating of metal surfaces, said he is certainly not opposed to industry. “I think we need some light industry to improve employment,” he said. “I’m all for it.”

But his own company operates from the Cortez Industrial Park and has been careful to use dust control and all appropriate mitigation, he said. So he was surprised that the pumping station’s operators were reluctant to do anything to help the neighbors. Years ago, when Whitaker lived in another house in the same area, he complained to the companies that then owned the station, Williams and Questar. “They sent out a guy, but we never got any resolution. They just said, ‘Sorry, guys. These are our residential mufflers already on it’.”

Jack Spence, a retired chemistry professor who lives about a mile away, said the noise can be loud at his place too. “It depends on the direction of the wind and on how many of their compressors are running,” he said. For people living closer, the noise intensifies exponentially. Those closest to it experience noise that is “way above what it’s supposed to be, 55 decibels at the maximum,” according to Spence’s calculations.

When another expansion of the pipeline was proposed in 2001, Spence obtained a copy of the environmental impact statement and wrote comments to the BLM, which was overseeing the project because it was on public lands. “I was appalled at the poor quality of the EIS,” Spence recalled. He said a map showed the plant as being near Dolores and stated that no one was living nearby. “It was just ridiculous. I took a topographic map and marked 10 or 15 places that were within 3,000 feet of it and sent it to them, but they never answered.”

The BLM eventually gave the goahead to the expansion, but there was an economic downturn and Williams abandoned the plan, Spence said.

He said he believes the company should either install quieter electric turbines, or do as was promised by running only at night and at a much lower volume. “But that reduces the capacity of the line and they’re interested in getting the maximum amount of gas down to Texas,” he said.

Lighting the sky

Of course, most of the people now living near the compressor station moved there after the original small station was in place, but not all of them. Dave Petillo was in his home in 1980 when the station was constructed just 200 yards away.

“At that point I was definitely the only one in this area,” he said. He knows there was a public notice and comment period, but he didn’t pay much attention. “I didn’t get involved,” Petillo said. “I knew there was going to be a pipeline, not that there was going to be a compressor station.”

But one morning he woke to the ground rumbling. “I looked out my bedroom window and there were four V-8 Caterpillars all over the hill, clearing the right of way,” he said. “That was when everything really hit me.”

When the station began operating, it was so noisy that Petillo talked to company officials. “They said it was just the start-up phase and that it was going to be quiet,” he said. But it was not quiet. And in later years the station doubled in size. Shortly after, there was such a huge flare from the station that Petillo called the fire department. “It lit up the sky,” he said. “The next day I got a call from a company official in Houston, Texas, saying if I had a problem I should call them, not the fire department.”

That is the only contact he’s had with any of the companies, he said. Meanwhile, the noise continues. “What it sounds like is a jet engine. It’s every day, but it varies in time,” he said. “It’s usually in the four-hour range per day, no more than that.”

At one point, he said, there was an even louder bellowing and red dust came out the top of the stacks. The company reportedly said “something got in the line and it destroyed one of the turbines.” In addition, there is sometimes a smell. “It hasn’t been very often, but at times you would definitely have to shut the windows and doors because it would burn your eyes.” Bright lights have also been a problem, but the company eventually adjusted the lights so they aren’t as intrusive, and Petillo keeps his blinds closed.

Petillo said he turns on a fan to mask the turbines’ sound at night, but if the wind is blowing from the south, he can’t sleep with the window open, even in summer. “It’s that irritating.”

Petillo said he recognizes that natural gas is needed, pipelines and compressor stations are needed, and jobs and tax revenues are important. But he believes he and his neighbors are being asked to shoulder too much of the burden for someone else’s profits.

“The people that own this place, they don’t want it in their backyard,” he said. “I would say within a half-mile radius you have maybe a hundred people around this thing. Why not try putting this in Cortez and see what response you would get?

“I just hope one day they run out of whatever they’re pumping out of the ground and it shuts down, because nothing seems to have deterred them.”

Feeling optimistic

Like the neighbors of the Mancos asphalt operation, neighbors of the pumping station have found it a frustrating experience trying to get the problem mitigated.

Ned Harper said he called the Colorado Oil and Gas Commission and a woman came out and measured the sound. She found that the decibel levels exceeded state rules, but said the COGCC had no jurisdiction because the pipeline originated out of state. Harper contacted the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission but said he was told that they did not have jurisdiction over liquid natural gas, only the gas itself.

The county has no authority because the station pre-dates the land-use code.

Neighbors have signed petitions, made calls, and written letters, but to no avail so far.

However, at press time Harper said he had spoken to a man with Enterprise Products in New Mexico who promised him the company would erect baffles around the working turbines to muffle the sound and would also redirect the exhaust so it points away from the nearby homes.

The Mancos Valley residents say things have improved greatly since 2007. Although more gravel operations have been approved at adjoining pits, and the county has given the go-ahead to the new hot-mix plant at the Noland pit, Burk is optimistic. She said the county commissioners have been receptive to residents’ concerns and it showed with the Ledcor proposal, which was passed with some stringent stipulations, including air-quality monitoring, county oversight of the testing, and required shutdowns for violations.

She praised the efforts of the commissioners’ attorney, Bob Slough, in working to achieve the stipulations and mitigations. “He understand; he listens,” she said. She also praised county planning director Susan Carver for being responsive and receptive.

Burk advises other citizens with problems to be persistent. “You have to stick wtih an issue. You have to be involved. It took us 2 1/2 years to get these gains.”

But there are still impacts, she said.

“After 2 1/2 years I have come to the conclusion that the noise and the dust — you can’t mitigate it no matter how you try,” she said.

Gosselin said she is also optimistic, but she still believes the concentration of industrial activities along that stretch in the valley is too much. “I can understand one gravel pit in the neighborhood, but now we’ve got three and it seems to me overkill.”

Gosselin said her father and grandfather were in the lumber industry and she knows industry is important, but it must be done right. “I really do believe in property rights and I do believe people should be able to do what they want on their own property if it’s not hurting the neighbors,” she said. “When what people do affects someone else’s property, that’s where the line should be drawn.”

So far, with two gravel operations going, “it doesn’t seem to be much of a nuisance,” Gosselin said.

But she said if she had been looking for a house during the summer of 2007, she would never have bought that tract. “If I’d been looking and that terrible smell was there, no, I wouldn’t have bought it. I just hope Ledcor will do what they say they’ll do.”