By Samuel Gordon

The Rocky Mountains hold dominant in this region. A bold and jagged spine of granite and sandstone that shifts the air currents enough to collect moisture in the otherwise parched west. The mountains stretch far into the cold north, into wolf country and past the Canadian border. In the east they roll into foothills, feeding the Padre rivers, North and South, with its tributaries, before stretching and flattening into the western reaches of the great plains.

In the west, and here, in the south, the mountains do not flatten. They shift ever so gradually. A transition occurs, jagged peaks rounding and cliffs stretching on horizontally. This is the land of prickly pear; of juniper mesas and grassland valleys, of desert canyons full of sagebrush, of slick-rock, of hoodoos, and of jackrabbits, rattlesnakes, and rock-sunning lizards. Locations counted amongst the hottest, driest land on earth, nevertheless still receiving freezing temperatures and possible winter snowfall. Deeper into the vast desert a person can travel, in two directions. I was told growing up that the desert went on and on until the sand met the ocean.

My entire life has revolved around my presence in the landscape around me. My connection to nature is intertwined with my wyrd, my destiny, who I am and where I am going. My life experiences could be compared to other cultures, but everyone is on their own path. No-one controls their birth.

My entire life has revolved around my presence in the landscape around me. My connection to nature is intertwined with my wyrd, my destiny, who I am and where I am going. My life experiences could be compared to other cultures, but everyone is on their own path. No-one controls their birth.

As far as births go, I can’t complain too much about mine. I was born smiling in Santa Fe, New Mexico. This ancient city is a desert maze of adobe. My first memories in childhood are of chasing lizards. Lizards sunning in the tan, brown, red hues of rock and dirt are plentiful in every pocket of land which is uninhabited by humans, and many which are. The adobe houses themselves provide suitable habitat for some, which have indubitably adapted to live alongside these pueblo-modeled homes scattered through the southwest.

I chased and caught lizards, among other small animals, careful not to harm them because I planned to bring them home. I had been taught since I was young that the lizards, the ladybugs, and the preying mantis are important. The lizards and other predators keep the bugs away. I caught lizards in the parks, in the empty lots, and in the alleyways. My favorite places to go though, were the dry arroujous. The twisting network of dry riverbeds, weaving under bridges and in between neigborhoods, are some of the most wild places left in Santa Fe. Few come here; only the lizards, the snakes, the foxes, and the pot-smoking youth of the city.

One day, a summer when I was in elementary school, I was visiting my dad. At the time he was living with a girlfriend on the edge of Santa Fe. She sells stone carvings in the style of the Zuni pueblo. He wanted to stay home that day, to read his book, but I craved an adventure. With much pleading I convinced them to catch lizards with me in one small canyon near the house.

My dad heard the noise first, and then I felt it. Only the two of us had gone down into the bottom of the arroyo. It was a growl. A small tremble that I could feel in the air as much as in the ground. I was struggling up the hill, my dad pulled himself to a ledge next to me and threw me the rest of the way up. He scrambled behind me. It was one of those slow motion adrenaline moments as I spun around. The first thing I saw was just a flying log; but the log wasn’t flying. It was pressed forward with a wall of brown water behind it, loose stones carried in the force and turbulence. Dirt was kicked up at our feet as the flash flood rushed past us, displacing the air like a stampede or a dust devil. The water ran hard for a few hours, full of debris, before slowing to a trickle, which ended and sank back into the dry soil before the end of the next day.

I remember standing in a canyon in Utah, cut through the grainy red sandstone by a similar force of powerful water, one that flows every day of the year. I didn’t yet know that one day I would paddle and steer my way across the the wave crests in this very river…

But a man can never visit the same river twice. He is never the same man, and it is never the same river. Change is the only thing in this world that can always be counted on to happen. The mountains we live in here in Durango were carved by changing forces of nature. Standing on the top of a peak, looking down at the eternally-forged veins of Mother Earth which stretch into the land where water and glacial activity has carved swathes and channels downward, it is easy to see. Standing on some peaks, I have looked down through the clouds at the frozen glaciers melting below me, still grinding their way across the land, toward the sea, as water always has.

The earth does more than destroy. So much is created; enough for all living things to sustain themselves. As I sit here, I drink osha root tea collected in these mountains. It is one of the few stored foods which I can still enjoy with my limited time and resources at the college. Osha will only grow in the mountains at a high elevation, and has adapted to survive hibernating through the long mountain winter. In the few short growing months, the edible greens of this osha I gathered had grown three feet tall in places, sometimes more. Digging through the earth with my hands, searching for the unique roots, I found a stone which assisted me while digging.

As plentiful as the osha may grow on this slope, I still felt bad for just how large my holes were. To gather the massive medicinal roots, I had to dig many holes which were two or three feet deep to find the bottom. Some of the biggest osha roots I have ever seen were gathered that day. Standing back as the sun set, my bag full thus my task finished, I observed my impact on the land. I cringed at the collection of holes, trying to push some of the soil back before leaving.

When I gather food and medicine from the land, I try to use the entire plant and not let any go to waste. But what is waste, really? In nature, waste does not exist. Energy does not appear from nowhere, and it cannot be destroyed. In the ecological recycling processes of decomposition, through fungus, insects, bacteria, and other microbes, all energy is recycled back into a system. Humans are the only animals which really create waste. We create products in the biome of Earth that will outlive our human bodies for millions of years. Toxins. Poisonous or radioactive particulate gases. Matter and concrete sprawl across the landscape, creating areas uninhabitable by all forms of life. Even extremophile bacteria which feed from radioactivity cannot survive on many “by products” of the typical American lifestyle.

My future is connected to the land as surely as I am. After seeing the beauty of the Earth and the parasitic tendencies of the human species, I cannot live without acting against what I know to be wrong. I have dedicated my future to the purpose. I am here going to school at Fort Lewis for environmental biology in pursuit of this aim; my lifestyle is already tied to the land, and my career will be to protect it.

You can acknowledge your heritage as an animal, a creature of this earth; or you can fear the wilds, and seek to conquer and to “civilize” the landscape. But we all live on earth, our island home. This is our air, our water, and our soil. This is the only home we have. What hurts the planet and the environment hurts all of mankind. We are the gatekeepers at a turning point in the biodiversity of life, because all life on earth is affected by the actions of our species. We are the history books of the future. Do something your grandchildren can look back on and be proud of.

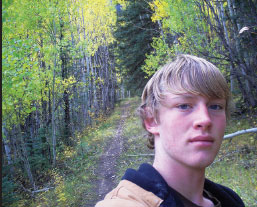

Samuel Gordon of Cortez, Colo., was a 2014 SWOS graduate, and a student at Fort Lewis College in Durango at the time of his murder during a home invasion on May 24, 2016. He was studying environmental and organismic biology. He would have graduated on April 29 of this year on the Dean’s List, having done so in only three years. His mother, Jeanette Phillips, says his friends consider him a hero. “They think he saved their lives that night, as all the residents were held at gunpoint and told not to speak or move,” she said in an email. “It was Sam who retaliated and fought back.” She is working on having some of his writings, such as this essay, published.