|

Related stories

|

“Ted” (not his real name) was no stranger to marijuana when he became ill several years ago. As a member of the Baby Boomer generation, he had smoked it — “of course,” he said.

“I smoked pot when I was younger for quite a few years,” he said. In fact, in the 1970s he was arrested for possession and served 2 1/2 months in a county jail; a much longer prison sentence was suspended. Eventually, however, he gave up the habit. Now a successful businessman in Montezuma County, he asked that his name be withheld because of the stigma attached to marijuana use, both medical and otherwise.

Several years ago, he began having vague but troubling physical symptoms and was ultimately diagnosed with Parkinson’s, a chronic, progressive and incurable disease of the central nervous system that causes trembling, muscle rigidity and loss of motor control. Its symptoms can be treated with several medicines, but their effectiveness is limited.

“Parkinson’s attacks one side of your body first,” Ted said. “My dominant side is my right side, which is the one that it chose. I was having real struggles writing with my hand, signing checks or making lists.”

One day he decided to smoke pot to see what effect it might have. “I was able to write normally for about three hours,” he said. “It also relaxed the rigid muscles.”

He talked to his neurologist, who said there were interesting studies being done regarding marijuana and Parkinson’s, but though the early results looked favorable, the long-term results were not in. At that time, medical-marijuana dispensaries were starting to open up in Southwest Colorado following the Obama administration’s announcement that it would not seek to prosecute people for using MMJ in states where it was legal. Ted decided to get a medical-marijuana card.

He had to pay to register with the state; a doctor at a local clinic reviewed his medical records, and he was officially an MMJ patient. (New rules passed this year mandate a stronger doctor-patient relationship for MMJ clients and require that physicians actually do physical exams of the clients.)

Now, Ted uses MMJ regularly. “Every morning after I do my exercises and drink a fruit smoothie, just before my workers arrive, I smoke about three puffs of marijuana. I don’t smoke any more the rest of the day and it seems to carry me through. It allows me to function. It alleviates a lot of my physical conditions. I’m able to work a full-time job; I have a very busy schedule.

“I probably could get along without it, but I certainly feel better with it.”

Critics have said that if marijuana is truly medicine, it should be regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, but Ted scoffs at that. “The FDA approves a lot of things that are crap – aspartame, MSG. It’s an agency that’s bought and paid for, like most everything that’s government-run.

“I think marijuana is a valid medication for a lot of people for a lot of things.”

Ted added that he believes pot should be legalized altogether — “I think victimless crimes are ridiculous.”

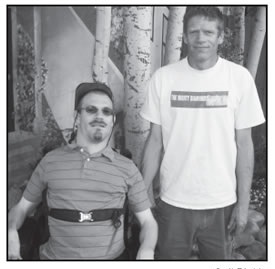

Chris Mackis (left) of Durango has seen improvement in his circulation and general health since using medical marijuana, according to his brother, Scott Mackis. Photo by Gail Binkly

Scott Mackis of Durango and his brother, Chris, agree. Both are MMJ patients — Chris for a form of cerebral palsy called spastic quadriplegia, and Scott for back pain following two serious automobile accidents.

Cerebral palsy is a type of brain damage that affects the muscles. In spastic quadriplegia, the entire body is affected. Muscles are stiff and rigid; because they cannot be relaxed normally, they may pull on bones, causing spinal curvature and other problems. Patients frequently have difficulty with speech as well.

Chris is confined to a wheelchair and has poor circulation on one side of his body. Part of his spine has been surgically fused and he has had hip-replacement surgery, Scott Mackis said, speaking for his brother.

About a year ago, because a friend with cerebral palsy was trying MMJ, the Mackis family decided to obtain a card for Chris. They visited a dispensary and purchased a topical ointment containing marijuana. At that point, Chris had been unable to open his hands for a month, Scott said.

“The muscles were so tight— it must be awful,” Scott said. “The lactic acid builds up. The first day, we got him home and put that salve on, and it was instant relief. He was able to relax his hands.”

Scott and his parents have been applying the salve to Chris’s whole body and believe it’s improving his circulation. “He used to have one cold foot. We applied it there, and it’s increased the blood flow and the warmth. It almost seems to get the electrical signals flowing to the nerves.”

They’ve continued to treat Chris with MMJ, mostly in the form of salve, though sometimes with edible products. (Chris is unable to smoke.) “I think it’s helping him in some other, subtle ways, because he’s more able to relax,” Scott said. “He’s said three or four new words since he’s been on medical marijuana. He seems to be making new neural connections.”

To Scott, who said he has had back pain for 20 years, marijuana is an alternative to opiate drugs, which he doesn’t tolerate well. “After my first wreck, they pumped me full of morphine and I left the hospital with withdrawal symptoms, so I decided not to get any more opiates.

“With herbs, I can quit without withdrawals. I quit for a year and tried to control my pain without it, but my quality of life was better with it. It’s been my only medicine since 1992.”

To Scott Mackis, the question of legalizing pot is a no-brainer. “I’ve been to multiple countries where it’s legal, or legal for medical use. The crime rate there was lower per capita than it is here.

“Colorado just got $9 million in application fees [from the Medical Marijuana Program Fund]. That filled a $9 million gap in the budget. To me, marijuana is creating jobs, it’s helping people, and this is money that is not going to the Mexican drug cartels.”

He also believes marijuana is no more dangerous than alcohol.

“What if people who drink had to get a card for their medicine? They’re self-medicating with alcohol for something.

“To me, legalization is just a logical step.”