The Dolores River quenches the thirst of many people, crops and creatures as it winds down from Bolam Pass through Rico and Dolores, across McPhee Reservoir, past the alfalfa fields of Dove Creek, and into spectacular desert canyons before merging with the Colorado River in Utah.

But dividing the water fairly among competing interests along the way — ranging from a native fishery and anglers to farmers and boaters — is a constant struggle for government agencies that control how the water is allocated.

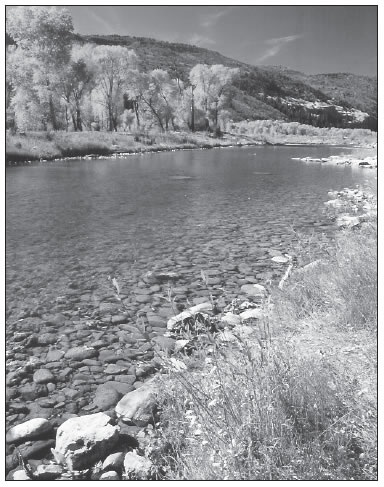

Management of the Lower Dolores River has spawned a number of controversies. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

To protect water rights while promoting preservation of the remote lower stretches, the Dolores River Dialogue was formed in 2004 to bring together different interests including environmental groups, recreationists, water managers and county, state and federal agencies for discussions and research.

After five years, some management ideas have emerged, and were presented at a DRD meeting in March.

Wilderness qualities

“The Dolores River Dialogue represents diverse groups with diverse interests,” said Don Schwindt, vice president of the Dolores Water Conservancy District. “We are still trying for consensus to move these contentious issues forward.”

The often-competing uses of the Lower Dolores have sparked acrimonious controversy in the past, especially over limited rafting flows and chronically low water levels for fish below the dam. But a professional and civil mood has prevailed more recently, a point that did not go unnoticed.

“Just seeing both of you standing together up there says a lot for this process,” observed fisherman Dale Smith, following opening remarks by Schwindt and Megan Graham, executive director of the San Juan Citizens Alliance, an environmental group.

The Lower Dolores River was recently designated by the BLM as “preliminarily suitable” for consideration as a Wild and Scenic River. Portions of the landscape along the corridor are being considered for wilderness or conservation-area status, all of which would potentially limit development (such as roads and oil and gas).

During the meeting, cooperation, communication and transparency of the process was touted as key to success. But outside forces can get in the way.

“I hear about communication all the time, but it would have been nice to be contacted when thousands of acres in our county were proposed for wilderness,” said Julie Kibel, a Dolores County commissioner.

“We don’t want to wake up with a new dog on our porch and not know whose it is,” chimed in Doug Stowe, also a Dolores commissioner.

They were referring to a recurring wilderness proposal presented to Congress every year by U.S. Rep. Diana DeGette (DColo). The bill proposes 34 areas on the Western Slope for designation as wilderness areas, including sections along the Lower Dolores.

With the Democrats in power, the bill received a congressional hearing in March for the first time in 10 years. U. S. Rep John Salazar (D-Colo.) testified that wilderness proposals need to protect water rights and evolve from a grassroots approach on a regional level rather than a sweeping proposal such as DeGette’s bill.

Forty or so professionals at the meeting grappled with minutia of proposal-vetting and final decision-making on management of the Lower Dolores. Underneath the veneer of cooperative spirit, the difficult nature of the negotiations was evident.

Schwindt said the DWCD needs to be kept in the loop more about special management areas proposed on the river below the dam, especially regarding any minimum flows associated with wilderness and Wild and Scenic River designations.

“The DRD has evolved and has history and clout, but how does this clout not get abused?” he said. “This is a large group and at times (the DWCD) has not known what was going on as much as we should have.”

A six-person steering committee representing various stakeholders is slated for drafting proposed recommendations for river management. The standing members are the Bureau of Reclamation, Colorado Division of Wildlife, DWCD, Montezuma Valley Irrigation Company, San Juan Citizens Alliance and Nature Conservancy. But there was concern that the even number of members could lead to a stalled process.

“Inevitably there will be some tough decisions not everyone agrees with, so I would suggest making it seven [members]” to break a potential stalemate, suggested Dave Vackar of Trout Unlimited.

But Schwindt and moderator Marcia Porter-Norton responded that consensus in the process made a seventh member on the steering committee unnecessary.

Native fish suffering

The Lower Dolores hosts a number of fish populations, both native and nonnative. Native fish include the roundtail chub, bluemouth sucker and flannelmouth sucker. Non-native trout are stocked in the stretches just below the dam for sport fishing.

Studies show a significant drop in native fish populations and range in the Lower Dolores since 1993, reported Dan Kowalski, an aquatic biologist with the Colorado Division of Wildlife.

“Their range has contracted significantly,” he said. “In a 53-mile stretch above Disappointment Creek where native suckers were common nowadays, there are very few when compared to historical numbers, so it is pretty grim.”

He said it is likely that the pikeminnow has gone extinct in the Lower Dolores due to a narrowing of the channel, low water levels and an absence of natural spring floods since McPhee dam was built. The pikeminnow, a predator that can reach 80 pounds and live 50 years, historically used the Lower Dolores to spawn in shallow sandbars and riffles cre ated by regular spring flooding. That sediment is captured by the dam now, Kowalski said, altering downstream habitat.

“The pikeminnow is a keystone predator, so its being absent is a significant difference,” Kowalski said.

The report of insufficient water levels due to the dam drew some criticism at the meeting. Not much is known about historic water levels on the Lower Dolores before 1982 due to substantial diversion projects dating back 122 years. In 1888, the Great Cut Dike tunnel began diverting agricultural water to Montezuma Valley from the Dolores River near Big Bend, spurring the growth of Cortez. Because Montezuma Valley drains into the San Juan River, not the Dolores, that water is known as a transbasin diversion.

Blaming McPhee is an “unfair comparison due to the transbasin diversion factor,” Schwindt said.

“Pre-dam is not natural either, so the question becomes, what is historic?” Kowalski responded. McPhee Dam and the reservoir were completed in 1987 and irrigate mostly land draining into the San Juan Basin as well.

The DWCD manages a “fishery pool” of 31,900 acre-feet in the reservoir for timed release below the dam over the year. Not counting rafting releases, the river typically receives 75 cfs during the summer months and drops to 30 cfs in the winter from the pool. Rafting spills do not count against the fishery pool, so for years when there is a boating season, the Lower Dolores will see slightly higher flows for the year.

The DOW biologists recommend a fish pool of 36,500 acre-feet with the ultimate objective of a year-round minimum flow of 78 cfs to improve the fishery.

The DOW reports that “the current fish pool is 43 percent of the minimum flow necessary to protect a barely viable fishery and protects less than five percent of native fish habitat.” Non-native rainbow trout are also in decline. On a positive note, just a little more water will lead to large habitat and population gains, the DOW reports.

“The Dolores River above the San Miguel River [confluence] has one of the poorest native-fish populations compared to other large western rivers,” Kowalski said. “The cause is insufficient flows.”

Another recommendation by biologists is to slowly ramp up rafting-flow releases earlier, beginning in late March and early April to better mimic a natural spring hydrograph that native fish are programmed to respond to for more successful spawning.

But that conflicts with the needs of rafters, who prefer a later release in May and June when the weather is warmer. Rafting releases range from 200 cfs up to 2,500 cfs for between one week and five weeks depending on the snowpack levels. Rafting spills are usually timed to include the Memorial Day weekend. During drought years, no rafting flows are released.

“Sustainability is how to balance natural values with human needs,” remarked Peter Mueller of the Nature Conservancy. “The rafting benchmark has been for recreation, so human needs are shaping the river” more than natural values.

A draft of the recommendations states that river permits will not be required for boating on the Dolores River, meaning private boaters can launch and float on any section in Colorado. (Permits are required in Utah sections.) Campsites will remain on a first-come first-served basis. The Slickrock put-in/takeout owned by the Randolph family will remain, but will be monitored for possible additional management in the future.

BLM river ranger Rick Ryan, now retired, also recommended camping only at designated campsites between mile markers 84 and 86. Additional posted campsites for small and large groups in this area may be created and enforced through a pilot program.

Overall, the Dolores River Dialogue process has improved awareness of the river and the importance of protecting it, members agreed.

“We are finally looking at the Dolores River as a watershed and not just incremental pieces of it,” said Vackar of Trout Unlimited. “When we bring together county, state and federal agencies in the same place and the same time to communicate, I don’t see how we can fail.”