A new study by the U.S. Geologic Survey indicates that the Grand Canyon watershed is susceptible to additional radioactive contamination from future uranium-mining.

The 350-page report was completed as part of a proposal by the Obama Administration to ban new mining in the mineral-rich region for 20 years to safeguard human health and the environment.

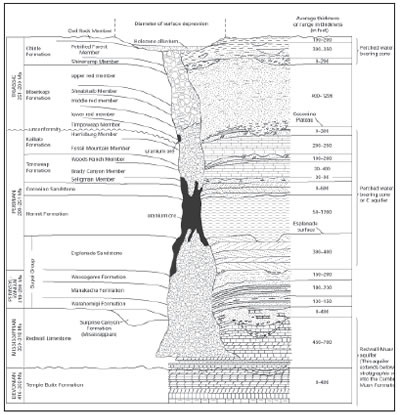

This shows a stratigraphic column of a breccia pipe showing relation of breccia pipe to surrounding rock, ore bodies, and perched water-bearing zones and aquifers. Photo courtesy of U.S. Geological Survey

Of special concern is the protection of aquifers and springs that discharge into the Colorado River, a primary source of drinking water for an estimated 25 million people living downstream. Several American Indian tribes in the immediate area also depend on springs and groundwater wells for their communities, as do native plants and animals.

Thousands of uranium claims, with dozens ready to be developed, are scattered on the mesas outside the boundaries of Grand Canyon National Park, which does not allow mining. One million acres north and south of the park boundaries are especially rich in uranium ore and are the target of a mineral withdrawal, or mining ban, initiated by U.S. Department of Interior Secretary Ken Salazar last summer.

For now the area is under a twoyear mining segregation ban, subject to valid existing rights (Free Press, March 2010), while an environmental impact study is conducted, which includes the USGS study.

Roger Clark of the non-profit Grand Canyon Trust says the region has suffered enough from irresponsible uranium-mining in the past and that protecting the Grand Canyon from further pollution is a national interest.

“Once the groundwater is contaminated, there is no remedy, so it becomes forever polluted, and that is unacceptable for Native tribes living there and all the downstream users,” he told the Free Press.

Rich uranium reserves

According to the USGS report, “uranium mining within the watershed may increase the amount of radioactive materials and heavy metals in the surface water and groundwater flowing into Grand Canyon National Park and the Colorado River, and deep mining activities may increase mobilization of uranium through the rock strata into the aquifers. In addition, waste rock and ore from mined areas may be transported away from the mines by wind and runoff.”

Northern Arizona contains significant uranium reserves, mostly found in “breccia pipes,” geologic features formed at least 200 million years ago. These vertical columns within the rock layers began as dissolved caves in the Red wall limestone, 2,500 feet below the surface. Progressive ceiling collapse over millennia formed rubble- filled columns that are concentrated with heavy metals including uranium ore, which is typically located 1,000 feet below the mesas.

There is an estimated 326 million pounds of uranium oxide within the proposed withdrawal area, which amounts to 12 percent of the total undiscovered uranium in northern Arizona. By comparison, the U.S. consumes 55 million pounds of uranium oxide each year in its nuclear reactors, most of which comes from Canada, Australia and Russia.

USGS scientists analyzed water samples from 428 sites in the region and reported that 70 sites exceeded maximum contaminant levels for uranium and other heavy metals.

Samples from 15 springs and five wells in the area contained dissolved uranium concentrations greater than the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency maximum contaminant level for drinking water of 30 parts per billion, according to the report. The contamination is caused partly by direct contact with naturally occurring uranium ore, but also by mining processes, the report says.

“Uranium mining has already contaminated lands and water in and around the Grand Canyon, and this research confirms that new uraniummining would threaten aquifers that feed the Grand Canyon’s springs, the Colorado River and nearly 100 species of concern,” said Taylor McKinnon, of the Center for Biological Diversity, in a press release. “These risks aren’t worth taking — and they’re risks neither the government nor industry can guarantee against.”

Contamination from the past

Heavy mining in the past has contaminated rivers and drainages in the Grand Canyon region that are still health hazards today. In the northwest corner of the study area, especially high uranium contaminations of 80 parts per billion were found in the Virgin River, the report states. Elevated uranium levels that exceed natural background levels also exist at the Kanab North mine and the Hack uranium-mine complex.

In 1984, a flash flood washed tons of high-grade uranium ore from the Hack Canyon mine into Kanab Creek, a tributary of the Grand Canyon. In 1979, the Church Rock (N.M.) mine waste ponds breached and flooded the Puerco River, a tributary of the Little Colorado, with millions of gallons of toxic sludge.

The closed Orphan Mine, on the Grand Canyon park’s south rim, also continues to contaminate creeks, prompting the National Park Service to warn backpackers along the Tonto Trail not to use water from the area.

The NPS also advises against “drinking and bathing” in the Little Colorado River, Kanab Creek, Paria River, Havasu River and others where excessive radionuclides have been found.

The study notes that samples of surface water from the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon typically contained less than 5 parts per billion of dissolved uranium.

Whether more mining will increase the release of uranium and other heavy metals into the major aquifers that feed the Colorado is a concern. Two main aquifers — the “C” about 1,000 feet below the rim, and the Red Wall-Muav located 3,000 feet down — naturally drain uranium and other metals such as zinc, silver, copper, lead, selenium, vanadium, and molybdenum into the Colorado River.

“Perched water-bearing zones,” which are separate from the aquifers, also feed springs and well water for local people, plants and animals. Breccia pipes loaded with mineral wealth intersect these zones, aquifers and groundwater reservoirs at various points, a concern because the pipes are targets for mining.

Burden of proof

The USGS had mapped more than 1,200 possible breccias pipes in the northern Arizona region and they are thought to possess high-grade ores. Traditional hard-rock mining with tunneling is used to extract the uranium, which is then shipped to the White Mesa Mill in Blanding, Utah, for processing.

Researchers fear that disrupting uranium and other ores through mining could cause increased infiltration of toxic heavy metals through rocklayers into critical aquifers that discharge into the Colorado River.

Hard-rock mining exposes uranium to oxidation, potentially increasing its solubility and therefore its movement into groundwater. Also, mine tunnels are susceptible to runoff and flooding that can unnaturally push heavy metals into aquifers, springs and rivers — a process that would not occur if the ore were left locked in the rock.

Geologic structures such as joints, fractures, faults, folds and bedding planes direct groundwater movement toward spring discharge areas and deeper aquifers, according to the report. Structural weaknesses along the Kaibab Plateau and on the south rim that host uranium-ore breccias pipes “have the greatest potential for remobilization of radiochemical elements” into the environment.

“Mining activity can result in changes to these habitats that may increase exposure of the biological resources to chemical elements including uranium, radium, and other radioactive decay products,” the report states.

“The identification of biological pathways of exposure and the compilation of the chemical and radiological hazards for these radionuclides are important for understanding potential effects of uranium mining on the northern Arizona ecosystem.”

In-situ mining, a relatively new and controversial technology that injects chemicals underground to dissolve uranium and then pump it out, is not used for breccia-type ore loads that dominate the Grand Canyon region.

“The burden of proof is on the advocates of uranium-mining to show it will not contaminate groundwater, and they have not done so,” Clark said. “There are no assurances in the USGS report that increased mining will not further contaminate land and water, so it is not worth taking the risk.”

The USGS study, titled “Hydrological, Geological, and Biological Characterization of Breccia Pipe Uranium Deposits in Northern Arizona,” can be accessed at http://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2010/ 5025.