A proposal to build a large and highly controversial waste-treatment facility in western Montezuma County won a unanimous thumbs-up from the county planning commission on March 26.

Despite efforts by Planning Commission Chair Jon Callender to limit speakers’ time and avoid redundant comments, the hearing soon turned into another of the grueling marathons that have come to characterize land-use debates in the county.

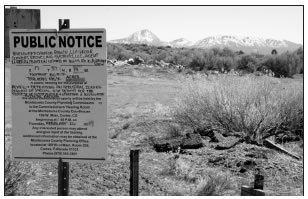

The old Lionfire campground on the Hovenweep Road is the site of a proposed facility for oil and gas wastes. The proposal passed the Montezuma County Planning Commission on March 26. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

The meeting began at 6 p.m. in the county annex before a crowd of more than 150, but the vote on the permit for the “Outhouse Recycling Facility” wasn’t taken till around 11 p.m. — at which time most of the weary audience had departed.

The project now is headed for a hearing before the county commissioners, where it almost certainly will (a) generate another lengthy, impassioned hearing and (b) eventually gain approval.

The hearing date had not been set as of press time, but was expected to be in May or later. The county commissioners said on March 30 that they would probably have to break with tradition and have the hearing at the annex or another large venue.

The proposed facility would accept and treat energy and production (E & P) wastes and petroleum-contaminated soils from the oil and gas industry. It would be located on 83 acres of a 473- acre parcel at 18655 Road 10 (the Hovenweep Road).

The owners are industrial developer Casey McClellan of Mancos and his brother, Kelly McClellan, of Farmington, N.M. Casey McClellan is a member of the planning commission but recused himself from voting.

The facility would include eight 4- acre ponds for evaporating liquid wastes from drilling and production of oil and gas and 8 acres where petroleum- contaminated soils could be spread for remediation. Casey McClellan said the life of the facility would be about 20 years, depending on demand, after which time the site would be “fully reclaimed back to native grasses.”

The March 26 hearing on the proposal was a continuation of a public hearing on Feb. 26.

First, the planning commissioners took up the matter of whether the tract of land should be zoned industrial. Even though no one, not even the applicants, seemed to want such zoning, it took more than an hour for the board to vote against it.

“This property is surrounded on three sides by Canyons of the Ancients [National Monument] and on the fourth by agriculture,” said Jerry Giacomo of Dolores. “If this were [made] industrial, it clearly would be spot zoning, which we all know is illegal in Colorado.”

“Why are you wasting our time with this?” Galen Larson, a rural county resident, then asked the board bluntly. “If it’s illegal, it’s illegal.”

Confusion

But the board’s subsequent 5-0 vote against the industrial zoning left many in the audience confused about how the project could then be approved without it.

Industrial and commercial uses of a wide variety can be allowed on agricultural and unzoned tracts under amendments to the county land-use code adopted in 2008 by the planning commission and county commission. The types of uses are broadly defined as “special uses that are temporary, created by nature, permitted by law or regulation, or are of unusual circumstance so that such a use can be accommodated without the possible detrimental long-term effects that a change to commercial or industrial zoning could have on the neighborhood.”

The special uses require a high-impact permit and special-use permit from the county commission.

Among the types of special uses specifically listed in the code as allowed are sewage systems, oil and gas wells, gravel mines, mobile asphalt plants, and special events such as concerts and motorcycle rallies.

However, language proposed for the 2008 amendments that would have added “public or private landfills” and “waste-disposal sites” to the list of specifically allowed special uses was removed during the July 14, 2008, public hearing before the county commissioners and was never adopted. At the time, several citizens objected to including such uses on the list, and the commissioners’s attorney, Bob Slough, said he did not think they belonged. There has been no discussion since of adding them, according to county planning director Susan Carver.

However, the list of special uses is not an all-inclusive list of the only uses allowed through the special-use-permit system.

The 2008 amendments have been controversial ever since they were proposed, but the planning and county commissioners say they are useful because they allow farmers and ranchers struggling to make a living to have some industrial or commercial activities and keep their land zoned as ag.

Others see the amendments as a giant loophole. Chuck McAfee of Lewis, a frequent critic of the county’s land-use policies, concurred that industrial zoning should not be given to the McClellan parcel but added, “It seems you can do almost anything on agricultural land regardless of what it is” and said the amendments are “inconsistent with the initial premises of the zoning system.”

“You shouldn’t be able to use a permit for 20 years,” agreed Hal Shepherd, former Cortez city manager, now a rural resident.

Not considered toxic

At the Feb. 26 hearing, citizens raised a number of concerns about the facility that were to be addressed by the applicants. The applicants’ 15-page typed response, however, was not presented to the county planning office until late the afternoon of March 25, according to Carver.

The response was promptly posted on the county web site and was handed out at the meeting, but its tardiness sparked criticism. Board member Guy Drew said, “I really don’t appreciate the timing of that. Had I had a job working 9 to 5 I wouldn’t have had the opportunity to view that. If I had been sitting in your [Callender’s] chair we would have continued this till the next meeting.”

Increased truck traffic on rural roads was a concern raised about a proposed waste site near Hovenweep, but proponents note that roads 10 and BB already see numerous oil and gas trucks. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

Environmental engineer Nathan Barton, agent for the project, took issue with opponents’ use of the terms “toxic” and “hazardous” to describe the waste facility. He argued that it was improper to use either label because the wastes do not fall under those terms as defined by federal and state law. “This is E & P waste as defined by federal and state law as related to oil and gas production and exploration,” he said.

E & P wastes uniquely associated with oil and gas were exempted by the EPA in 1988 from the provisions of the federal law that governs management of hazardous waste, though critics at the time said the decision was purely political.

The officially exempted wastes are the only types that will be accepted at the facility, Barton said. Such wastes will include produced water — water resulting when operators inject fluids into oil and natural-gas wells to force the precious substances to the surface — and drilling muds and petroleumcontaminated soils.

However, opponents of the project maintained that, regardless of legal definitions, the wastes would contain hazardous and toxic materials. Among the most toxic sustances used by the industry, they said, is fracturing or “fracking” fluid, a mix of water and chemicals injected during drillings.

Barton said produced water in this area is “9- or 10-pound water,” meaning that a gallon weighs 9 or 10 pounds instead of the normal 8 because of the high salt content. Most of the additional material is chlorides, carbonates and bicarbonates, Barton said.

Lynn Anderson of Road 10 said “produced water” is “really is a euphemism.”

“It’s really a chemical soup. Water is the carrier but there are all kinds of hazardous and toxic substances that are hazardous enough they don’t have to be present in high levels.”

Such sustances may include hundreds of chemical additives with harmful health effects, according to the Endocrine Disruption Exchange, a nonprofit based in Paonia, Colo.

Anderson said produced water is frequently involved in spills, and cited spills of more than 1 million gallons of water containing E & P wastes that occurred in February 2008 near Parachute, Colo., migrating through the ground and into Parachute Creek.

“This proposed waste facility is on high ground that slopes toward Hovenweep Canyon,” Anderson said. ‘It’s scary but easy to imagine a similar scenario.”

Board member Tim Hunter criticized Anderson for mentioning the Parachute incident, saying that facility was for wastes from “coalseam production.”

“It’s a surface facility to contain water with hazardous substances, and heavy snowfalls caused it to overflow,” Anderson responded.

John Wolf of Pleasant View said the liquids could be also contaminated by radiation if the drilling pushed through layers of rock containing uranium. However, Barton said such formations are rare and usually thin.

Proprietary information

Betty Ann Kolner of Road BB cited an incident that happened in July 2008 in Durango, when an emergency-room nurse at Mercy Medical Center who had treated a worker involved in a spill of frac fluids became critically ill herself. While she hovered near death from organ failure, the company that made the fracking fluid (a brand called ZetaFlow), refused to disclose its chemical content because it is considered “proprietary information.”

That prompted Dominic Spencer of the Bill Barrett Corporation, an energyexploration company that has been very active in Montezuma and Dolores counties, to say that all operators have the required Material Safety Data Sheets for the fluids they use present on location at drill sites.

John Wolf of Pleasant View cites his concerns at a Montezuma County Planning Commission meeting March 26 about a proposed 83-acre facility for oil and gas wastes. Photo by Gail Binkly

However, Lynn Patrick of Mancos, a naturopathic doctor, said the MSDS sheets can be vague. The sheet on ZetaFlow lists a “proprietary phosphate esther,” not the specific chemical compounds. She said chemicals used by the energy industry can cause many serious adverse health effects.

Spencer said Bill Barrett does not use ZetaFlow, but another brand with different ingredients.

‘Respectful listening’

It was clear there was widespread concern about the project. Opponents presented petitions; Carver said later she had counted 746 signatures, although she couldn’t say if any were duplicated. And most of the citizens who spoke at both meetings voiced opposition to the facility.

However, some favored it.

Chuck Banks of Farmington, N.M., a former Cortez resident, cited the need for jobs in the area.

Gregg Tripp of County Road P, a petroleum engineer, addressed one question that was not explored in much depth — whether it was better to have E & P wastes left on site at numerous scattered drilling locations than to have a central facility. He commented, “We say we don’t want it in our backyard. If we don’t do it, we’re going to have it in everybody’s backyard because it’s going to be in every one of those locations. Make sure it’s managed correctly, but we still need to do it.”

As the audience grew tired and fidgety, tempers heated up, and mumbled comments about the speakers — on both sides of the issue — grew louder.

“We aren’t going to have any tourism at $6-a-gallon gasoline,” grumbled someone after a comment about impacts to the national monument.

“Get me a tree to hug,” snorted another man when Scott Clow of the Four Corners Recycling Initiative was advocating that the produced water be “put back where it came from,” by injecting it back into the ground.

“In 20 years we’ll all have cancer!” cried an audience member on the other side of the issue when Nick Richins of Vernal, Utah, predicted that in 20 years there would be a new energy source and sites for oil and gas wastes would no longer be needed. Richins added that he had showered that morning with gas-heated water and had driven to the meeting using fossil fuels, remarks that drew considerable applause from part of the audience.

Callender was at last forced to admonish the attendees to engage in “respectful listening.”

‘A bit hypocritical’

The applicants answered the concerns by citing the need for such a site to encourage energy production in the area and stating that it would follow all laws and regulations and was unlikely to cause problems for neighbors.

Casey McClellan said the project would have economic benefits far beyond the two full-time people it would employ. By keeping waste-disposal costs lower for energy companies, it would encourage further drilling, meaning that oil and gas workers would spend money in the economically depressed area and more new homes would be built.

In a response to concerns expressed at the February meeting by monument manager LouAnn Jacobson about the site’s proximity to the monument’s signature ruin, Painted Hand, McClellan said, “It’s a bit hypocritcal to say, we’re OK with the 250-plus wells that are already in Canyons of the Ancients. . . but we’re not too happy with the piece of private property that wants to clean up E & P wastes.”

McClellan and others also cited the fact that oil and gas development provides 40 percent of Montezuma County’s property-tax revenues. However, of that 40 percent, the vast majority — more than 90 percent — comes from carbon-dioxide production, not oil and natural gas. CO2 produces fewer wastes of the sort that would be handled at the facility.

In response to concerns that the project would mar the beauty of the Trail of the Ancients scenic byway, Barton said the byway — which includes Highway 491 north and county roads BB and 10 — already contains many other commercial and industrial sites. However, none of those are on Road 10 except an 80-acre waste facility on the Utah side that handles asbestos and petroleum- contaminated soils.

The applicants said they had shifted their original site one-quarter mile to make sure it would not be visible from the road.

Barton also pointed out that the byway was chip-sealed several years ago with money that came from an energy-impact grant and that the paving had helped tourism.

Concerns had been expressed about traffic impacts to the narrow county roads. The facility would not be required to pay impact fees under the land-use code because the applicants say it would not generate more than 15 vehicle trips per day, the threshold for such fees. However, Carver told theFree Press she intends to propose that the applicants enter into an agreement with the county to pay some road maintenance costs.

Several citizens urged the board in vain to table the proposal for further study.

“If this goes by without one official word of caution, that’s a travesty,” said M.B. McAfee of Lewis. She advised the county to consult experts in energy development and have an independent panel to review the application as well as to plan for energy development locally on the broad scale. “There’s no need to hurry. The resources aren’t going away.”

The planning commission did not apparently ever entertain the idea of not recommending approval for the permits. However, they forwarded to the county commissioners suggestions for many stipulations to accompany the permits, including requiring third-party environmental monitoring of water and soil both on and off site, posting all monitoring data on the web, preparing a traffic study, demonstrating dust control, monitoring wind activities, erecting wildlife fencing, chip-sealing interior roads to reduce dust, and creating a night-time mitigation plan.

A ban on night-time operations to which the applicants had agreed was nevertheless removed from the motion.