New backcountry tours take hikers into Mesa Verde’s hidden areas

Mesa Verde National Park is opening up access to remote ruins as part of an effort to improve the visitor experience on a trail less traveled.

Daily guided hikes into the backcountry offer adventurous tourists and locals a chance to escape the crowded tour groups shuffling around the park’s signature ruins such as Cliff Palace and Spruce Tree House.

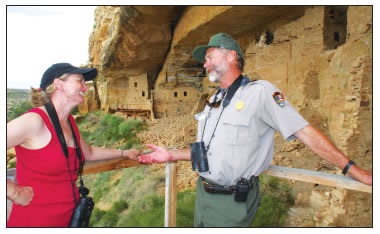

Margi Puhls asks a question of Tom Wolf, interpretive ranger, during a hike to Spring House at Mesa Verde National Park. The park is offering new, guided hikes to several backcountry areas. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

“We’ve become known as an asphalt park to some extent, and these new tours are a way to offer something special for those willing to hike for a while,” said Tom Wolf, an interpretive ranger. “It’s a way for the park to give back to the community.”

He is guiding four of us on an 8-mile excursion across mesas and in and out of rugged canyons. Our destination is Spring House, a rarely seen, and incredibly stillintact ruin complex tucked into an alcove off Long Mesa.

The air is cool as we start off at 8 a.m. on a recent Saturday with backpacks filled with water, sunscreen and sandwiches. We descend a paved trail into Spruce Canyon, passing dozens of roosting turkey vultures enjoying the morning calm before the hordes of vacationers arrive.

We’ve all got a spring in our step as we pass through a locked gate and around a barricade with a sign telling other visitors that the area is off limits.

A surprisingly well-built network of (non-paved) trails crisscrosses this remote section of the park’s closed backcountry, a legacy from the heydays of the 1930s and ’40s, explains Wolf.

Back then the Civilian Conservation Corps brought young men into the park to build miles of trails as civic employment during the Great Depression.

“What they didn’t tell them was that most of their paychecks went back home to their families, but they didn’t mind too much because they had a job with meals in a place like this,” Wolf says.

In fact, before Mesa Verde closed off these trails to protect remote ruins from looters and vandalism, the area was popular with picnicking tourists exploring the region on horseback, he say. Well-buttressed switchbacks, artful rock retainer walls and stone-lined drains are a testimony to the masonry skills and labor of those workers. Along their trail to Spring House we have excellent views of Buzzard House, Teakettle House and Daniel’s House and several well-preserved signal towers and granaries.

Hikers, especially locals, have been critical of Mesa Verde because of the lack of longer trails (Free Press, May 2005). But with so many great trails unused, why are they closed?

Park archaeologists wrestle with the balancing act of protecting ruins from looters, and offering the public a close-up look at early human history in the area as it would have looked back then. The daily guided backcountry tours are an experiment, Wolf explains, a compromise that offers more access while also protecting the fragile sites from unsupervised exploration.

“They want to see how it goes, so we have to be very careful. So far it has been wildly popular and we’ve had a very positive response from people taking the tours,” he said. “Observing ruins in a more natural setting is great for visitors, and some rockjocks sign up just because they love the workout of canyon hiking.”

We dodge flags warning us to watch our step to avoid the endangered Mancos milkvetch growing along the trail as we climb up Wickiup Canyon. As if on cue, a law-enforcement ranger, Tim Cook, emerges onto the trail and joins our group. He’s a reminder of the importance of patrolling the area to protect the archeological and natural resources.

“I love the new tours; it has given me a job,” Cook says, explaining that the park hired two additional rangers to monitor the extra trail activity and offer assistance such as radio communications, first aid and transport if hikers require it.

Increased patrols have already netted “lost” hikers exploring closed areas without a guide. They are rounded up and ticketed with a $110 fine.

We all have our binoculars on a small dwelling tucked high onto a sandstone ledge. Soon, we spot a modern resident — a goshawk, standing large in the doorway of a cliff dwelling, protecting her chicks nesting inside.

“One of our archeologists spotted her,” Wolf said. “It is pretty rare for animals to take up residence in the ruins but there she has found a good spot.”

We top out on Long Mesa, and eat lunch enjoying panoramic views of Mesa Verde’s southern flanks. Then it is on to Spring House, which requires some scrambling down to a ledge, descending wooden ladders and using ropes to shimmy along slickrock to a narrow rock corridor that opens up onto a platform overlooking the impressive Spring House ruin.

As an art museum’s collection comes alive with the help of a docent, interpretive rangers breathe life into the diverse Puebloan culture that thrived here 1,000 years ago.

“The cleverness of the architecture and the sites chosen for defense are absolute genius,” Wolf says of the four-story Spring House ruin. “They made it hard to get into this site.”

We marvel at the 800-year-old wooden beams still holding up buildings, and contemplate a spring that feeds an ancient vanity in one of the rooms. Large potsherds litter the rock shelf below; one is a complete upper half of a black-on-white pot.

The ruins beyond the beaten track at Mesa Verde are kept in their original condition, Wolf says, without artificial anchors or interpretive re-building of fallen portions. Leaving things alone evokes a ghostly aura of a time long gone.

“Imagine this full of people, with lots of activity, not silent like it is today,” he says.

In Navajo Canyon, an ancient reservoir shows off the ingenuity and farming skills of the Ancestral Puebloans, formally referred to as the Anasazi.

Wildlife abounds in Mesa Verde’s backcountry, including this rattlesnake. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

Further on the trail we startle a baby rattler basking on a rock and he hisses and strikes at air from a safe distance, falling over backwards in the process. These back canyon bottoms teem with bird life, including swifts, blue-gray gnat catchers and broad-tailed hummingbirds.

We’re silent climbing back to civilization, and after all that hiking our hunger makes it it easy to imagine ancient fires roasting wild turkey with sides of beans in the cliff alcoves and dwellings. But we settle for a beer and a cheeseburger at the cafeteria.

“I’ve been here nine times this summer showing relatives and friends the same ruins, but today was by far the best time I’ve had at Mesa Verde,” remarks Margi Puhls who hiked along with her husband, Don to Spring House for the first time.

“I am so glad they opened it up for us to see.”