In 1978, 24-year-old Bruce Hucko was doing his best to find work outside Salt Lake City, where he taught photography to school kids. He’d fallen in love with the outdoors, so he applied for a job as a National Park Service photographer. No luck.

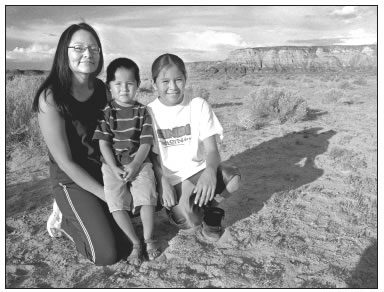

An exhibit by Bruce Hucko on display at the Anasazi Heritage Center depicts residents at Montezuma Creek, Utah, as children years ago and as adults today. Here, Roberta Topaha is shown with her family. On Page 20 is her photo as a young girl. Photo by Bruce Hucko.

He was considering traveling to New Jersey to work for an uncle, when the Utah Arts Council invited him to conduct a two-week workshop at Montezuma Creek Elementary School on the Utah strip of the Navajo Nation. He accepted, and at the end of the class, the principal offered him a job as an assistant to the kindergarten teacher.

Hucko grabbed the opportunity. “For the first time in my life I listened to that little voice of serendipity.” His laugh booms over the phone from his studio in Moab, Utah.

Thirty years later, the choice has led to “A Gesture of Kinship,” a traveling show sponsored by the Utah Museum of Natural History, for which he has shot many photos. Presenting 20 students as Hucko first met them, and as they are now, “Gesture of Kinship” currently hangs at the Anasazi Heritage Center near Dolores, Colo.

Hucko began work on “A Gesture of Kinship” his first morning in Montezuma Creek. Besides helping the kindergartners, he covered American Indian Day activities for the local paper. Many of his students had never seen a camera. Curious, they tried to pull Hucko’s off his neck.

“I decided, ‘This is going to hurt’ after a while,” he recalls with amusement. “I’d better get some cameras to put into their hands.”

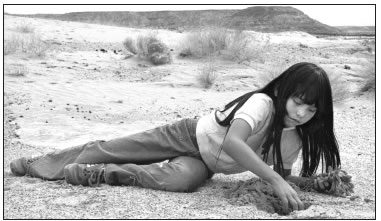

Roberta Topaha of Montezuma Creek, Utah, as a young girl. Her photo as an adult is on Page 18. Both photos are part of an exhibit currently on display at the Anasazi Heritage Center. Photo by Bruce Hucko.

With donated and secondhand equipment, and the little darkroom in his 10-by-15-foot trailer, he began teaching photography. As he took his Navajo, or Diné, students on field trips, their families got to know him. He found himself herding sheep and participating in birthday celebrations and traditional ceremonies.

He gained enough trust to start photographing the people. “I came for two weeks and stayed 10 years.”

When he finally left, he maintained the friendships he’d made. Then about five years ago, he and University of Utah anthropology professor Donna Deyhle received a grant from the university to revisit Montezuma Creek.

Hucko photographed his former students as adults and asked about changes in their culture, community, and themselves. Deyhle placed their responses into the larger context of Native American history.

As he asked questions, Hucko found that buildings, roads, and landscapes had changed little since he’d left. Something else had changed tremendously. The media had arrived.

“Everyone [was] plugged into some thing,” he observes, recalling how few people outside of town had electricity, let alone TV, when he lived there. “Now, take half the boys at White Horse High School and drop them into East L.A., and you couldn’t tell them from anyone else. There are a lot of questions about cultural identity now.”

Yet many of his former students said they felt close to the land, when he spoke to them. Young adult boom-box listeners learned Navajo and traditional teachings from their fathers and grandfathers.

“Change is what Navajos have always done. That’s a tradition in and of itself,” Hucko says.

His students’ love of their surroundings made him decide how to present “Gesture of Kinship.” Using a digital camera, he made color snapshots of their homes, and superimposed the new and old photos on the landscapes.

The show consists of 20 32-by-40- inch panels of merged text and image. “Just the same way the kids view their position on the land. It tied together very nicely.”

The title “A Gesture of Kinship” comes from the importance of kin to the Navajos. People introduce themselves first by clan and then by name, to indicate how they might be related.

Though he uses digital cameras, he loves working with the chemical photo process. “Nothing is quite as exciting as being in a darkroom where you don’t have a clock.”

The color of the safe lights transports him to a timeless and unique environment, especially with music playing. “You do the work. If something doesn’t get done right, you look in the mirror and say, ‘I messed up.’”

Living in Montezuma Creek gave Hucko a different perspective on photography. Before arriving, he wanted to shoot the wilderness, not people. The Diné changed that attitude.

“It was burned into me that trees and rocks are living organisms. You can ask them to smile for the camera just as you can ask your niece and nephew to smile when you want to photograph them.”

The people in “Gesture of Kinship” enjoyed doing the project. All have copies of their exhibit panels. Many who did not participate want to tell their stories for another show.

“I think I have some more work to do,” Hucko says with gladness. “There are lots of ‘then and now’ projects. But how many people get to. . . carry on a long a relationship, or have tools [to] bring that long relationship to some form of completion, and share that with. . . the world?”

“Gesture of Kinship” will hang at the Heritage Center through Oct. 31. The center is also showing a small collection of prints Hucko’s students made so many years ago in his darkroom.