Thirty-six artists moved out of their personal comfort zone to place work in the current art exhibition, “Connections: Earth + Artist = A Tribute Art Show to Resistance to Desert Rock,” on display at the Center for Southwest Studies at Fort Lewis College, Durango.

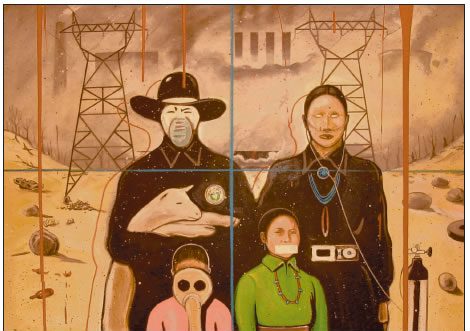

This painting, “Bleeding Sky” by James Joe, was chosen Best of Show at a new art exhibition called “Connections,” which showcases resistance to the proposed Desert Rock power plant in northern New Mexico. The exhibition is on display at the Center for Southwest Studies at Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colo. Courtesy photo.

Desert Rock, a proposed 1,500- megawatt power plant that would be built in northwest New Mexico, has been touted as an economic boon to the Navajo Nation, but others worry about its effects on regional air quality and health.

The topic polarizes people around environmental issues, jobs, spirituality, traditionalism and big business.

The Diné are split on the Desert Rock debate as well. Some jobs will be “made available to a few but we will all be subjugated to the aftermath,” says Shiprock artist James Joe (Diné). “Dirty air knows no boundaries and we Navajos have to recognize ourselves as Mr. Greed and Mrs. Apathy, too.”

According to exhibition curator Venaya Yazzie (Diné/Hopi), “A lot of Navajos have lost the idea of living a good life, what it is like to be a Navajo, living, walking in a good way. They don’t really know where to plant themselves.”

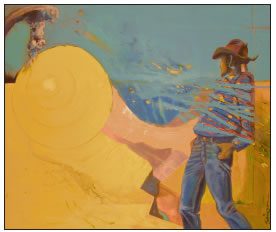

The painting “Dear Downwinder” by Ed Singer depicts a Navajo cowboy blown over by yello wind. It was inspired by an official government memo sent to residents downwind of nuclear test sites years ago.

Elouise Brown (Diné) is president of the Dooda’ (Absolutely No) Desert Rock opposition camp at Burnham, N.M., where Sithe Global Power is proposing to build the third coal-fired power plant within a 20-mile radius. Yazzie met with Brown for a day and came away with a commitment to support Dooda’ Desert Rock.

She enlisted the proposal help of poet, educator and artist Esther Belin (Diné) who agrees that a visual art and poetry exhibition reaches a broader audience. “This exhibition opportunity takes the polemics out of it, giving back the experience, the ownership to the viewer,” Belin adds.

Submissions were open to all artists, all ages. But Yazzie is glad her own generation, especially, is participating because they “are living for their own comfort; the coal plant, air quality, new uranium explorations near Grants [N.M.] are too much of a problem to think about — out of sight, out of mind. The material world and self matter more now than what my grandparents believe.”

In the best-of-show painting, “Bleeding Sky,” artist James Joe paints a traditional Navajo family in a future landscape depleted of beauty and life. They hear no evil, speak no evil, see no evil, taste no evil. Consequently, they are suffering, changed.

“The big power structures behind them are seductive juggernauts walking toward us today,” Joe says. “We must recognize that we have lost our way on the Turquoise Road, our common sense. It’s like peeing in your pants. It will keep you warm for only so long, but the end results are devastating.”

Unpopular social causes are familiar to artist and poet Gloria Emerson (Diné), from Shiprock, N.M. “My family has been social-political activists for generations. Dooda’ Desert Rock is an honorable and difficult, complex protest for Elouise Brown and those speaking out at Burnham. The exhibit is a way for me to support their work and help get the issue into the general American public.”

Her painting, “Desert Rock,” serves as a reminder “to pay attention to those forces which intend ill fortune, counteract them with positive action.”

“Connections…” is purposeful and narrative. The language in the exhibition title is specific, “…Tribute…to the resistance at Desert Rock.” It is not a protest show. It is a tribute to resistance — the fundamental responsibility to get informed, speak out, and care about the future consequences of our choices.

According to Durango artist Ricardo Moreno inclusivity is part of the Desert Rock solution. “Many individuals may believe that their point of view is the most important. However, that does not deal with or resolve the other conflicting points of view.”

His computer-generated drawing, “Transcend Dualism,” is a map of the Four Corners superimposed over a Yin-Yang symbol. Five sets of dualities are placed around the circumference of the symbol as if they are outside the debate, waiting for an opening: affluence- poverty, society-environment, them-us, mountaindesert, here-there.

“When all perspectives are not addressed, the ignored issue will appear again, more than likely manifest itself to a stronger degree,” Moreno said. “Open, honest dialogue may help raise awareness, bring more clarity, perhaps, even a more creative resolution to the issue.”

Poet Tina Deschenie (Diné/Hopi), editor of the Tribal College Journal based in Mancos, Colo., agrees that the exhibit helps bring awareness.

“Whenever any structure is being planned, a visual drawing [blueprint] of it is made and put out in the public for review. It is the same with this exhibit. It takes the discourse from the place location at Desert Rock and renders it into the open for the public to view and consider.”

The day the paintings were due at the center, internationally recognized artist Ed Singer (Diné) telephoned Yazzie to let her know he had left Gray Mountain, Ariz., for Durango — a fivehour drive. Yazzie says, “His modesty is typical of the artists in “Connections…”. He didn’t complain about the difficult drive to get to Durango, cost of gas or the fact that he was working all day on the first Navajo Nation wind farm at Gray Mountain. He didn’t even mention that.”

All exhibitions are professionally important to Singer, but “Connections…” parallels the wind farm as a positive social, political, economic and environmental project.

“I am proud to be included because the exhibit shows purpose beyond decoration and entertainment. It is our chance to tell a story and learn. I hope that my work makes the audience rethink their ideas about colonizer-colonized, oppressor-victim, documentarian- object, museum-artifact, as well as artist-model.”

The title for his painting of a Navajo cowboy knocked over by a ball of yellow wind was taken from an official government memo sent to residents near Gray Mountain:

“Dear Downwinder, Some of you have been inconvenienced by our tests… you have accepted without fuss, without alarm and without panic…we are grateful for your continued cooperation… Feb 1955.”

The exhibit will remain open to the public through Sept. 28. For more information contact the Center for Southwest Studies, 970-247-7456, http://swcenter.fortlewis.edu, 1000 Rim Drive, Durango, CO 81301.