The San Juan National Forest’s proposed Salter Y Vegetation Management Project is intended to help both the forest and the timber industry, but it has drawn concern from recreationists. The question of forest health is key. Photo by Gail Binkly.

“People love big trees. Whether they are hiking, biking, riding – people notice them.People just love the fact that there are big trees and ecologically we need to keep the big trees.”

— Jimbo Buickerood, San Juan Citizens

Alliance

Part I of a two-part series

Out-of-town visitors as well as residents of the Four Corners region in search of big trees often frequent local areas in the San Juan National Forest (SJNF), in the northeast section of Montezuma County.

This area to the east side of McPhee Reservoir is accessed by travelling north of Dolores on County Road 31, known as the Dolores-Norwood road, as well as FS Road 527, the Boggy Draw Road and FS Rd 528, the House Creek Road which leads to a boat ramp and campground on the edges of McPhee reservoir.

Locals often refer to these areas as Boggy Draw, the Glade, or “our backyard.”

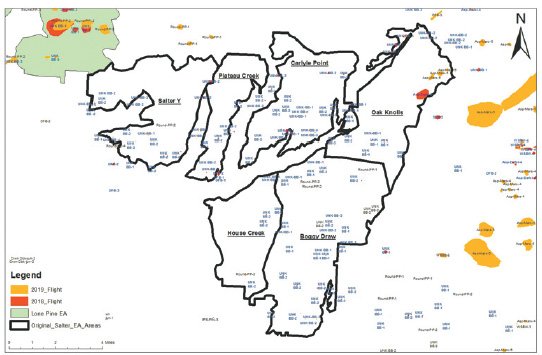

The area within the black boundaries is proposed for treatments in the Salter Y project, which would include commercial logging and prescribed burning. Graphic by Janneli Miller.

But is that backyard healthy? What makes for a healthy forest, and what should be done to maintain or create one?

Those are questions the Dolores Ranger District of the SJNF is considering as it weighs public reaction to the proposed Salter Y Vegetation Management Project, which would treat 22,346 acres of public land in this region north of Dolores.

A paradise

Visitors to this region of the national forest can engage in year-round recreational activities, which the SJNF website says include bicycling, camping and cabins, climbing, fishing, hiking, horse riding and camping, hunting, OHV riding and camping, outdoor learning, picnicking, scenic driving, water activities and winter sports.

Indeed, this area is promoted on the Town of Dolores website as being “an outdoor enthusiast’s paradise.” The Dolores Chamber of Commerce lists the Boggy Draw Trail system, the McPhee overlook trail, the San Juan National Forest and McPhee Lake in its promotional materials, mentioning swimming, kayaking, rafting, hiking, biking, cross-country skiing and fat-bike snow riding as recreational activities.

The proposed treatment area has few older ponderosa pines with broad-diameter trunks. Photo by Janneli Miller

In the fall, the area is utilized by hunters, with eight permitted outfitters providing guide services then, eight offering winter use, and six offering guided fishing services. Other permitted outfitters provide Jeep, OHV and dirt bike tours, mountain bike tours, and llama pack tours, and 13 outfitters provide summer educational and family trips.

Included in this area are 11 active individual livestock grazing allotments. According to the Draft Environmental Assessment for the Salter Y project, “ponderosa pine forests in the analysis area are considered suitable for livestock grazing and do provide understory vegetation for livestock forage to varying levels.”

Any visitor will notice that there are a fair amount of cattle in the area, especially in spring and fall. The local national forest truly is a multiuse area, enjoyed by many.

Indeed, due to the pandemic limiting international travel and out-of-state vacation options for many, this area of Southwest Colorado has seen escalated activity. (See the July 2020 Free Press). Increased visitation, including dispersed camping and both motorized and non-motorized trail use, has been noted by local residents and forest users.

More people using the area means more impacts to wildlife, vegetation, limited water sources, and roads and trails.

In addition, the forest is currently suffering from the combined impacts of extended periods of drought and bark beetle infestations.

In response, the Dolores District proposed the Salter Y Vegetation Management project to increase forest diversity and health.

“The San Juan National Forest is critical infrastructure for our community, providing natural resources, recreational opportunities, and capturing and filtering the water that we all depend on,” Rebecca Samulski, speaking as concerned citizen and a volunteer with the Dolores Watershed Resilient Forest Collaborative, told the Four Corners Free Press.

“Keeping these nearby forests healthy is important to all residents of the Four Corners, as we become more aware of the role healthy landscapes contribute to human health.”

First cattle, then logging

In the past, places with natural resources were seen as places that existed primarily for extraction, and a reciprocal relationship in which humans contributed to restoring the places they exploited was not so much a part of the thinking. The result of the early resource extraction and fire suppression is apparent in today’s forest, which consists mainly of dense, even-aged stands of ponderosa pine.

The first white settlers in the area came in the late 1870s, usually with cattle. In 1879 Charles Johnson brought in 2,000 head of cattle, Henry Goodman brought in another herd of 5,000, and the Quicks and King brothers brought more in 1880.

Ira Freeman, writing in A History of Montezuma County, mentions that “cattle were everywhere.”

It was open range and soon the region had a reputation as good cattle country, which lasted through the first wave of settlement. By 1882 the entire Dolores River Valley was settled.

The rich grazing range ran out around 1910, and interest shifted to logging. The first sawmill established in the region was in the town of McPhee in 1874, and in 1897 a lumberyard was established.

The New Mexico Lumber Company received access to logging rights in the Montezuma National Forest near Dolores, which had been established in 1905. McPhee, a lumber company town (the site is now under McPhee Reservoir) grew quickly.

In 1924 New Mexico Lumber purchased 400 million board-feet of yellow pine, logged within a 55-square-miles area seven miles north of Dolores. In 1927, McPhee was the most productive mill town in Colorado, producing more than half the state’s lumber – 30 million board-feet cut annually, according to Lisa Mausolf in the NPS publication The River of Sorrows.

These early loggers cut the biggest ponderosa pines, and the impact is still apparent today in that the area is largely devoid of big old trees and snags.

The area was harvested again in the 1940s. In the 1980s an effort to regenerate and reforest was carried out. Overgrown brushy areas, consisting mainly of Gambel oak, were mowed, and restocking of seedling trees was performed via an interplanting method.

The resulting forest – which users see today – is a mix of dense same-age mature ponderosas, open areas with no tree regeneration, and brushy oak thickets. The entire area has been harvested, and regeneration efforts have been spotty, leading forest planners to begin their current efforts to restore vegetation to more diverse growth. “What we have seen in stands lacking an uneven aged structure is scenarios where the stand converts to almost brush with only hope of persisting is reforestation,” Derek Padilla, Dolores District ranger, explained in an email to the Free Press. “Essentially losing the quality habitat associated with a Ponderosa Pine overstory unless intervention.”

The Little Bean Trail is one of many sites in the area proposed for treatments, including logging, in the Salter Y Vegetation Management Project, which is being considered by officials with the Dolores Ranger District of the San Juan National Forest. Photo by Janneli Miller

The increased drought conditions prevalent locally can stress trees and make them susceptible to bark-beetle infestations. Places with infestations have been noted in the area.

“Currently, there are isolated occurrences of insect activity throughout the Salter analysis area,” Padilla said. “Fortunately, they are not large in size at this time. Projections are difficult. We have seen in an area northwest of the Salter analysis area, areas that started out as isolated insect activity areas that resulted in significant mortality and then we had other areas with similar insect activity that did not result in significant mortality.” The Salter Y Vegetation Management Project is expected to begin in 2023. By “treating” the forest, managers hope to increase forest diversity, thus mitigating potential damaging impacts to the trees from fire and beetle infestation.

Samulski said the current large-scale vegetation management projects “have the ability to really start rehabilitating our forest.”

“We do not have several-hundred-year-old ponderosa pine trees out there to keep,” she said. “In order to get a diverse forest, that has to be grown over time, with some of the surplus of medium-sized trees out there now perhaps becoming those big yellow-barked pine trees in another century.” Needing restoration Jimbo Buickerood, lands and forest protection program manager for the nonprofit San Juan Citizens Alliance, told the Free Press, “The basic situation is that the ponderosa forest in general, after years of fire suppression and the way timber harvesting was managed, or not, and grazing, but mostly logging – is in need of restoration.

“Restoration means that what we’re trying to do is that we want the forest to be more diverse. Diversity is strength and resilience. SJCA would like to see the forest with a more diverse age class and size class.” Padilla said forest health is definitely related to forest diversity. He believes the Salter Y Vegetation Management Project is necessary for the “development of resilience to disturbance, mainly insect and fire.” “This EA focuses on beetle resiliency but has desired conditions that lend to fire resiliency,” Padilla said. “Beetle resiliency focuses on uneven-aged management with basal area spreads from 50 to 70. Most of our stands are deficient in 27-inch or greater diameter trees but also seedling and healthy pole-sized trees.

“Bark beetles have a tendency to focus on large-diameter trees first and taper off at a lower diameter to almost no hits in trees 5 inches in diameter and below.

Trees in the proposed Salter Y treatment area tend to be dense and uniformly aged, thanks to clearcut logging in the past. Conditions make the forest vulnerable to bark-beetle outbreaks and catastrophic wildfires. Photo by Janneli Miller

“As bark beetles attack a stand with only large trees and succeed in killing off most of the overstory without seedling and pole cohorts, the stand has the potential to lack the stocking to promote regeneration and succeed in resiliency.” The Salter Y Environmental Assessment, which was released in February, explains the need for the project as three-pronged.

Proposed treatments are intended to:

- improve resilience and resistance to epidemic insect and disease outbreaks,

- increase the structural diversity of the ponderosa pine forest represented across the landscape, and

- provide economic support to local communities by providing timber products to local industries in a sustainable manner.

The proposed project will include four kinds of treatments, depending upon the specific area, type and quality of trees.

The Boggy Draw area has become popular for recreation year-round. Cross-country skiers here did their best to ski even when the snow was melting in March. Photo by Gail Binkly

Impacts to recreational areas, including roads and trails, and dates when logging will take place, were incorporated into the treatment plan. For instance, the Environmental Assessment states that no logging will take place during Escalante Days in Dolores when the Rotary Club holds a mountain bike race on trails in the proposed project area.

During logging the EA states that there could be as many as 24,000 loads of forest products hauled on the Dolores Norwood Road, with maybe as many as nine loads a day coming through the town of Dolores for nine months of the year. The treatments include single tree selection, commercial and pre-commercial thinning, post fledgling area treatment (PFAT), and brush thinning. (See below)

The maximum diameter to harvest would be 26.9 inches in single tree cutting, and up to 22-inch-diameter trees in the PFAT treatment areas.

The proposal includes three options:

- Alternative 1: No action

- Alternative 2: Modified proposed action • Alternative 3: Large tree retention.

No tree larger than 26.9 inches in diameter at breast height would be cut in alternatives 2 and 3. For the average stand in the project area, the residual basal area would be 60-to-68 square feet/acre depending upon the silviculture treatment. Interestingly, on the SJNF website project information, the project purpose is listed as “forest products.” Buickerood is concerned that the Environmental Assessment did not include any common stand exam information.

“What they’ve identified is that there’s a lack of seedlings and a lack of older larger trees,” Buickerood said. “Their actions will help with the seedlings, but unless you are specifically retaining some older larger trees you’re doing nothing to help at the other end of the diminished number of older larger trees.

“All that adds up to a timber project more than a restoration project.I’m afraid that the economic piece is too tilted towards forest industry. Frankly it seems to be giving industry some contracts.”

Padilla disagreed, telling the Free Press “To be clear, forest-product removal is a tool to achieve desired conditions, which is the number one priority. While providing forest products provides an economic driver to the community, economics is secondary to developing healthy forest conditions in a sustainable and ecologically sensitive way.” The Salter Y EA was open to public comments through March 10. At press time, the district was reviewing the 123 comments it received. The next step is a 45-day “objection period,” estimated to begin on April 1.

“When working on improvements, there are always short-term impacts,” Samulski told the Free Press, “but we must invest in these kinds of projects and sacrifice for a short time in order to move our forest to one that can better grow grass and forbs in the understory and that can absorb the impacts of disturbances including wildfires and insect and disease outbreaks.”

The second part of the series in the May issue of the Four Corners Free Press will elaborate on the project’s process, with information on potential environmental impacts as well as scenery, transportation and recreational use. Public comments addressing the project will be covered as well.

Proposed vegetation treatments

The following information on four different types of treatments in the proposed Salter Y Vegetation Management Project was provided by the Forest Service.

Single Tree Selection: An uneven-aged regeneration method where individual trees of all size classes up to 26 inches diameter at breast height are evaluated and removed more or less uniformly throughout the stand creating or maintaining a multiage structure of groups, clumps and individuals to promote growth of remaining trees and to provide space for regeneration.

Commercial Thinning: Silviculture “Free Thinning” with enhancement objectives in mixed stocking ponderosa pine with a variable residual square feet of tree stem basal area of 50-70 basal area per acre depending upon stand condition. Individual trees of all size classes up to 26 inches diameter at breast height are evaluated and removed throughout the stand creating or maintaining a multiage structure of groups, clumps and individuals.

Post Fledgling Area Treatment (PFAT): PFAT prescription is a free thinning in which trees of all size classes up 22 inches are evaluated for harvest while retaining a 100-to-120 residual basal area target. A focus on large groups of 20-30 trees or more is desired with internal clumps made up of 3-to-5 large and mature trees with interlocking crowns.

Pre-commercial Thinning: Thinning of ponderosa pine (Less than 5 inches diameter) to variable spacing specifications. Would be implemented in any treatment unit.

Brush Thinning: Thinning of understory brush species (generally target brush less than 6 inches diameter at root collar), mainly Gambel oak; to create openings for seedling recruitment and reduce ladder fuel effects on residual trees. Would be implemented in any treatment unit. This prescription is limited to treating no more than 5,000 acres.