Wild horses that live at Mesa Verde National Park are considered “trespass livestock” and are being removed because they compete with wildlife for the park’s scant water resources. Meanwhile, Grand Canyon National Park is working to remove bison. TJ Holmes/Courtesy of National Mustang Association of Colorado.

Which animals belong on the public lands of the West? Which are part of the historic landscape and which are intruders? And how should the intruders be handled?

Managers of public lands of all types are struggling with such questions, but such issues can be particularly difficult when national parks are involved. And nowhere is that clearer than at Mesa Verde National Park near Cortez and Grand Canyon National Park in Arizona.

Mesa Verde is home to several bands of free-roaming horses that are judged to be “trespass livestock.” After years of analysis and planning, operations to remove those animals are beginning.

Bison on the North Rim of Grand Canyon National Park are causing ecological damage, as seen here. Courtesy of National Park Service.

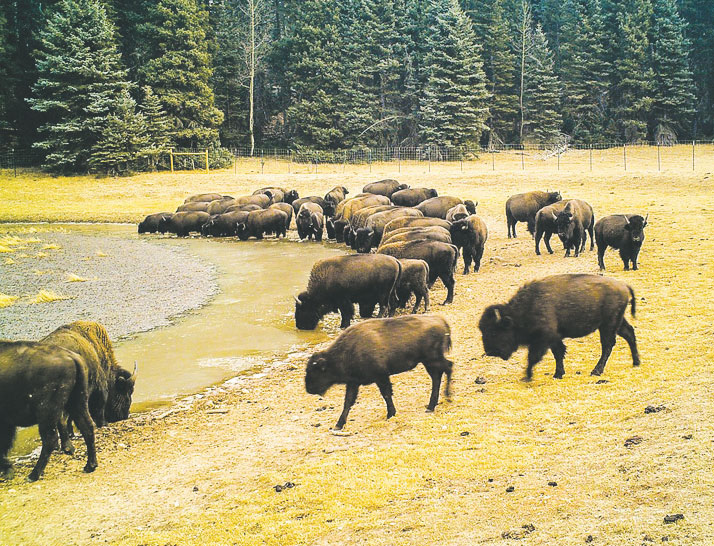

And Grand Canyon has been implementing measures to reduce the size of a bison herd that lives on the North Rim of the canyon and has been reproducing bountifully. Those measures include allowing hunters to kill a dozen of the shaggy beasts.

Both situations – and the plans for dealing with them – have sparked some opposition and controversy.

A landmark act

Debate is continually raging over whether wild horses belong on America’s public lands. In an opinion column in October in the Durango Herald, Fort Lewis College History Professor Andrew Gulliford called wild horses “the scourge of the West,” saying they harm ranchers by taking forage away from cattle and sheep.

The efforts at the Grand Canyon to control the bison herd have also sparked controversy. In a letter dated May 4, several animal-welfare groups wrote to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland to voice concern over the planned bison hunt.

2021 marks the 50th anniversary of a landmark piece of legislation, the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971. Passed unanimously by Congress and signed by President Richard Nixon (who actually signed a great deal of environmental legislation), it declared wild free-roaming horses and burros “living symbols of the historic and pioneer spirit of the West” and protected them from “capture, branding, harassment, or death,” adding that “to accomplish this they are to be considered in the area where presently found, as an integral part of the natural system of the public lands.””

“Gunsmoke had just gone off TV. There was still a palpable Western nostalgia [when the act was created],” said Nathan Brown, interim chief of natural resources and biologist/wildlife program lead at Mesa Verde National Park. Brown spoke to the Four Corners Free Press in a phone interview.

The act directed the Bureau of Land Management and U.S. Forest Service to seek out horses that were descendants of the stock the Spanish originally brought to the Americas when they arrived. Then the agencies, with help from a number of biologists and horse advocates, “drew circles on maps” to create herd management areas where wild horses would be allowed, and set objectives for how many animals the areas could support.

“They said, ‘Knowing there are also four grazing allotments for cattle and one for sheep, for example, how many can this area support?’ This was pre-climate change, 1970s science. And that’s how it went for 30 or 40 years.”

The act came about after fury arose over how wild mustangs were being treated prior to the legislation. At that time horses were commonly slaughtered for meat in the United States, and the wild populations were rapidly disappearing. One activist who became known as “Wild Horse Annie” saw horses being hauled to a slaughterhouse in a truck so cramped that blood was leaking from it because one animal had been trampled.

The 1971 act helped mustang populations rebound – but then the opposite problem developed, when populations grew too high for the specified herd management areas to sustain.

Most of the responsibility for handling wild horses fell to the BLM, which manages the majority of the herd management areas. Subsequent legislation allowed the use of motorized vehicles and helicopters to round up horses and burros to bring the numbers down. The animals were put up for purchase or adoption, but many were never adopted and wound up in long-term holding facilities.

The problem of what to do with excess horses has only increased since then.

“There’s been a lot of change in America since 1980,” Brown said. “Not so many Americans can afford to keep horses any more.”

“Now there are holding pens throughout the West with tens of thousands of horses in them,” Brown said. “The homes just aren’t there for them. That’s the major issue.

“When Congress passes a budget, they give money to the BLM to implement this program [the Wild Horse and Burro Act], but roughly two-thirds of that goes to take care of the animals being held. It’s sort of a conundrum.”

The situation at Mesa Verde is complicated by the fact that the horses in that park – there are believed to be about 70 – are not protected by the 1971 act because they aren’t judged to be truly wild.

“The Mesa Verde horses were not part of the 1971 act,” said Brown. The federal regulations governing parks say that unless the presence of livestock was written into the park’s founding legislation, he said, “you really don’t have the legal authority to manage livestock, which is the position we are in.”

The federal regulations use the term “trespass livestock” for animals such as these, he explained.

“When Farmer John’s horse or cow gets into a park we will capture it and they can claim it and we can get restitution for feeding and capturing it,” Brown said. “There is a legal process, but there is not a legal process for feral animals. It doesn’t exist in federal regulations. It’s wild horses and trespass livestock. What we have in the park is a combination of the two.”

Wild or trespassing?

Horse advocates disagree with how the Mesa Verde horses are labeled.

“It’s a controversy looking for an issue,” said Lynda Larsen, a board member of the nonprofit National Mustang Association of Colorado, in a phone interview with the Free Press. “In my mind all wild horses in this country are at some level feral. A horse that’s born in the wild is wild. That’s not domestic stock no matter how you look at it.

The horses at Mesa Verde are gradually acclimated to panels and pens, rather than being subjected to stressful round-ups like those done in the past on public lands. Courtesy of National Mustang Association.

“Mesa Verde characterizes these as trespass livestock, but we differ with that at some level because horses were roaming that area before it was made a park. To the extent any of them originated from domestic stock they haven’t been domestic for a long time.”

Concern and anger arose in 2014, a drought year, when six horses died of thirst in the park after their access to water was blocked.

“There are very few springs and water sources in the park,” Larsen said. “And in many years there’s not enough grazing and horses die. It’s not a good situation, especially with the changing climate.”

The park set to work planning how to remove the horses. A 2018 environmental assessment said they needed to be captured and taken from the park – although there were thousands of public comments recommending just leaving the horses there.

“Livestock need to be removed because the National Park Service does not have the legal authority under 36 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Subpart 2.60, to allow livestock use in the MVNP,” the EA stated.

“As of 2017, park programs and practices, including maintaining fencing along its boundary, have not been effective at removing and preventing livestock from entering the park,” the EA also said. “There are approximately 80 horses and 12 head of cattle distributed throughout the park; no burros, goats, sheep, or swine are currently in Mesa Verde National Park. The number of trespassing livestock, particularly horses, has increased in the past 20 years and the recruitment rate has surpassed the rate of removal. . . .”

Many urged the park to use birth control on the mares, but park officials say it isn’t feasible or legal for them to do so.

“We have advocated birth control since the beginning,” Larsen said. “Their position is they can’t do that because that’s a management tool. The only reason they’re able to bring water and hay to the horses is as part of the process of trapping them. They can’t do it on a regular basis or it would be management.”

And roughly 70 percent of the public lands in the Western states, not counting Alaska, is actively grazed by livestock, he said.

The problem posed by wild horses in excess numbers is a genuine one across the West, Brown said. “If you have a thousand horses instead of 100, that ecosystem sustains impacts. There are impacts to cattle and sheep and native wildlife. The horses will be a detriment to other uses.

“They don’t have natural predators, for the most part. The annual recruitment exceeds the natural mortality.

“Horse advocates may say, ‘Why don’t you remove the cows and sheep?’ But the act doesn’t say we’ll have wild horses to the exclusion of other uses. We know how many cows and sheep are there. Those animals are moved around and aren’t there all year round. It is a managed program where managers look at the forage available. They do manage them. They are implementing the Taylor Grazing Act, which is a major component of the BLM mission.

“The greater livestock industry in the 10 or 11 Western states is a good chunk of those states’ economies’ portfolios. Tourism to take pictures of wild horses isn’t the same.”

According to BLM statistics, of the 245 million acres the agency manages, livestock grazing is authorized on 155 million acres, while wild horses and burros are allowed on slightly under 27 million acres of BLM land.

Water hogs

And at Mesa Verde, Brown said, the horses are taking water from wildlife. He said there is photo evidence showing the horses displacing elk at water sources.

“We’re supposed to conserve the national and cultural landscape at the park,” he said.

There are people who question whether elk themselves are native to Mesa Verde. Brown said they were certainly native to the San Juan Mountains at some point and while there were likely never great numbers of them in Southwest Colorado, “we have historical records of elk in the park and in the San Juan Mountains.” There are petroglyphs showing elk, he said.

“They are a native species – whether on the Mesa Verde plateau I don’t know.”

Horses also take water from birds and amphibians at the park’s springs, he said. “There has been environmental degradation of limited hydrological resources and archaeological resources. Elk, deer and bears resources. Elk, deer and bears move around, but horses won’t leave a water source.”

“The functionality for other species has been diminished at the water holes,” he said. “The hydrologic footprint on the mesa has been shrinking anyway. The number of springs producing water and the amount of water has been shrinking as things change, so the impact of horses is magnified.”

An acquaintance of his who lives where the Colorado Plateau and Great Basin join – an area that gets 10 inches of precipitation a year – told him that you can have livestock, you can have horses, and you can have wildlife there, but you can’t have all three. “You have to pick two. That’s from her perspective of 30 years of experience,” Brown said.

The decision to remove Mesa Verde’s horses was firm. But park officials, who talked and worked with the nonprofit National Mustang Association of Colorado, opted to follow the horse advocates’ recommendations for low-stress methods of capture.

“Instead of using the cowboys-and-helicopters approach we are using a low-stress approach, trying to minimize the stress level for the animals,” Brown said.

That involves baiting the horses with water and hay, and getting them used to seeing humans. That effort began in 2019 and seemed to be working well.

“Within a couple of weeks, they were running after the truck for water,” Larsen said.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic brought a halt to the operation and it had to be restarted in 2021.

A fairly sophisticated holding pen and chute with a gate that can be closed remotely was constructed to hold the animals that are baited into coming inside. The captured horses will be inspected for brands and held for a period of time to make sure no one claims them. Then they will be released to the National Mustang Association.

Larsen said the park should be congratulated for the way they have handled the recent efforts. “We’re very pleased they’ve been on board with using the low-stress methods,” she said. “I think it’s been six years we’ve been meeting with them. They have been great to work with.”

“Mesa Verde is really trying,” Brown said. “We’re trying to do it the best way.”

Ultimately, a single stallion was captured this year. After his 30-day holding period, he was taken to a ranch in Montezuma County and has been doing well, Larsen said.

“This horse is very mellow,” she said. “He’d never been touched by humans, but he had seen humans because he was hanging around the park campground.

“He’s now in a round pen and has been fed handfuls of hay through the fence. Patricia Barlow-Irick [a famed horse trainer and the director of the nonprofit Mustang Camp] was able to pet his face.

“I think this is testimony to the way he was gathered. It wasn’t fear-based at all. The old round-ups could be brutal.”

When the stallion is considered ready, he’s to be taken to the Mustang Camp in New Mexico for training to make him more adoptable. Barlow-Irick has tamed over 500 wild horses, Larsen said.

“An approachable and trained horse is 100 times more likely to get adopted,” the Mustang Camp says on its website.

The rest of the horses at Mesa Verde will eventually be captured and also trained so they are more adoptable, Larsen said.

“It will take several years, but it’s hoped that next spring, with the infrastructure completed and a couple of bands acclimated to the water trough and eating hay, progress can be made,” she said.

The National Mustang Association of Colorado is seeking donations to help with the cost of transporting and training the horses, which costs $2,500 to $3,000 per horse, Larsen said. Donations can be made at www.NMACo.org.

Keeping them out

Solving the horse problem at Mesa Verde also involves attempting to keep new ones from coming into the park. A population of feral horses that belong to no one live on the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation, which adjoins Mesa Verde’s southern border. These animals aren’t protected by the 1971 act, Brown said.

The park is replacing different sections of boundary fence to try to keep them out, but it isn’t an easy task. “The source population on our southern border is largely unmanaged,” he said. “We have mesa and canyons. The topography lends itself to trespass-livestock scenarios.”

Although horses are the main trespassing-animal concern, Brown said, they aren’t the only type of animal that has invaded the park. Recently a pig was captured, he said, and people also dump cats within the park’s boundaries.

“I trap them and take them to the Cortez Animal Shelter, but I’m sure none of them are adopted,” he said.

True bison now

The problem of unwanted animals is a problem for national parks across the country.

“This is not a problem unique to us,” Brown said.

While Mesa Verde wrestles with removing horses from its boundaries, Grand Canyon National Park is having a problem of its own with herbivores it says don’t belong – bison on the canyon’s North Rim.

Bison and a calf on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. Courtesy of National Park Service.

These animals are labeled and treated as wildlife, according to Joelle Baird, public-affairs specialist with the park, who spoke to the Free Press by phone.

Traditionally, before the arrival of non-indigenous people, bison lived around much of North America. The Grand Canyon’s North Rim would have been at the very terminus of their natural range, Baird said. No bison bones have actually been found in that area so far, and no bison were known to live there until about 100 years ago.

The current animals, the Kaibab herd, are descendants of a herd that belonged to a man named Charles “Buffalo” Jones who bred them to cattle to try to make better animals for beef. His efforts didn’t turn out as he’d hoped, and by 1930 the 50-member herd had been sold to the state of Arizona.

Starting in the 1950s, Arizona Game and Fish issued permits for hunting the bison, who were staying at House Rock Valley just east and north of the park. The hunts kept the herd’s numbers down and hunters paid a steep price for a chance to kill a bison.

But the smart and wily animals eventually drifted into a safer place.

“There is a lot of hunting pressure on the Kaibab National Forest,” Baird said, “and the bison know where the boundary is. They will occasionally go to the Kaibab – there are water tanks over there – but in the last 10 years they have really preferred to stay within the park boundaries.”

Hunting is not allowed in Grand Canyon National Park.

Interestingly, despite their origins, these bison have been determined by genetic studies to be less than 2 percent cattle.

“They are more or less true bison at this point,” Baird said.

The herd has now grown to about 600 and is causing considerable ecosystem damage, especially to meadow areas where the bison graze and wallow.

“In the last 10 years the park began actively considering ways to reduce the numbers,” Baird said. “Bison have no natural predators on the North Rim. The only pressure is from hunters.”

In 2017 the park issued a finding of no significant impact for a plan to reduce the herd to about 200 animals using both lethal and non-lethal methods.

The lethal method entailed a pilot program allowing 12 volunteers to kill one bison apiece in 2021. The volunteers were chosen by lottery from more than 45,000 eager applicants.

Removing a dozen bison from a population of 600 doesn’t sound as if it would accomplish much, but Baird said the point of the cull isn’t just reducing numbers.

“It’s less about the actual number of bison taken and more about concentrating on the effort to impact the movement of the herd itself. It’s so they see the park as less of a refuge.”

The lethal operations have been going on over the past month, Baird said, in a highly controlled and monitored way.

The skilled volunteers are tied to a team of Park Service personnel, she said, and safety is paramount.

“Every skilled volunteer is being held accountable. We have an entire day of training. It’s a very controlled setting in that way. The volunteers have a lot of oversight from our park staff because they know the area. We are not letting volunteers just out in the park at large to shoot.”

The focus is on shooting females to reduce the reproduction rate. In the autumn, the females aren’t pregnant or nursing calves.

Other bison are being captured and taken out of the park. So far, 124 have been taken from the North Rim and transferred to six Native American tribes in the Great Plains states, Baird said. This effort has been going on for three years,

“Every year we will reassess and see where the population numbers are in the herd,” she said.

The lethal approach has drawn some criticism.

“It may be euphemistically called a cull, but the NPS is to conduct a lottery to select participants, allow the lottery winners to enter the park with firearms, and authorize them to gun down bison and leave with the carcass and trophy,” several animal-advocacy groups wrote in a letter to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland in May.

“This is at odd with the statutory and foundational value for Grand Canyon. . . .”

In the letter, signed by Wayne Pacelle, president of Animal Wellness Action, the groups argued that concerns about bison’s impacts to the park “are exaggerated and more a matter of aesthetics than ecology. . . . Like any animal of its size, they will leave footprints on the land, consume forage and water.”

The groups said the decision to offer hunting opportunities “is not a serious-minded plan to address meaningful ecological problems, but instead a political action designed to appease a few enthusiasts for trophy hunting. . . .”

When burros were a problem in Grand Canyon, they were removed through non-lethal means, Pacelle noted in the letter.

The groups urged the use of birth control for the bison.

However, that isn’t really feasible, Baird said. “Fertility treatments have been proven to work in places, but there are inherent challenges in getting close enough to the bison here.

“Our bison are not like traditional bison you might find in other areas of the country such as Yellowstone, where you drive through and take pictures of them from your car, or the Great Plains.

Marvel, a 3-year-old stallion, was captured at Mesa Verde using low-stress methods and taken to a local ranch.

“People think of them like cattle in that way, but we have a very different type of herd on the North Rim. These bison are used to wooded areas and are very adept at hiding. They are afraid of humans. It’s very challenging to get close to them. You never hear about our bison charging visitors on the North Rim.”

Baird said although there is certainly opposition to killing or removing the bison, there was quite a bit of public support as well, particularly from people who have spent time on the North Rim. “People would drive in and they used to see long grasses in the meadows and find wild orchids on the springs, and this has been changing since the herd has grown.”

Bison aren’t the only animal issue in the park. There are a number of wildlife-management issues involving non-native species, including elk on the South Rim. That herd, which has no predators, has been growing, and although it isn’t causing as much damage as the bison, the population is being closely monitored by biologists, Baird said.

“We do have issues of livestock coming into the park,” she said, mainly on the South Rim. “It’s not uncommon to see feral horses and cattle. We are actively working with tribal members for capturing and relocating horses and livestock.”

Some other national parks are home to bison herds, including Yellowstone, of course, as well as Theodore Roosevelt National Park in North Dakota. That park has been very successful in transferring its excess bison to other tribes.

But while both Mesa Verde and Grand Canyon are moving forward with plans to remove or manage animals they consider to be of particular concern, the problem of non-native creatures on national parks is endemic across the country.

In a 2019 report, CNN said “the number of invasive animal species in U.S. national parks has put the protected lands under a ‘deep and immediate threat’,” citing a new study published in the Biological Invasions journal.

The report urged the Park Service to adopt a system-wide approach to the situation rather than acting on a park-by-park basis.

“The global threat of invasive animals substantially undermines the National Park Service mission” the report said.

Birth-control shots are used to manage horses on BLM lands

Managers of both Mesa Verde and Grand Canyon national parks have decided that the use of birth control is not feasible for controlling the growing horse and bison populations in their parks.

But birth control does work on animals in other places.

At a talk at Mancos Public Library on Oct. 29, Kat Wilder, a horse advocate and author of Desert Chrome: Water, a Woman, and Wild Horses in the West, praised the relationship that horse advocates have with the Bureau of Land Management in handling wild horses on BLM lands.

Wilder said there are 177 herd management areas across the West, four of those in Colorado. One in the Disappointment Valley in Southwest Colorado is home to the Spring Creek Herd Management Area. “We’re lucky to be working in close partnership with the BLM there,” Wilder said.

TJ Holmes, a horse advocate and photographer who had an exhibit at the Canyons of the Ancients Visitor Center showing photos of the Spring Creek horses, said that herd has been successfully managed using birth control.

Mares are given shots of PZP, an annual pregnancy-preventing hormone made from pig ovaries. Holmes herself uses a rifle with a CO2 cartridge that propels the dart into the mares’ hindquarters. The dart then is ejected and falls to the ground.

The goal is to keep the herd down to three to five foals a year through the annual injections, and so far it has been working. The Spring Creek Herd hasn’t had a roundup in the last 10 years.

Birth control is now being used in all four herd management areas in Colorado, the women said.

Resources

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/15/us/wild-horses-adoptions-slaughter.html

https://americanwildhorsecampaign.orghttps://www.mustangcamp.org/