In 2001, a foreign species of beetle with a voracious appetite for the invasive tamarisk plant was released as part of the largest bio-control experiment in U.S. history.

And although eight years later the plan is succeeding in killing off the most despised non-native shrub of the Southwest, the law of unintended consequences has also come into play.

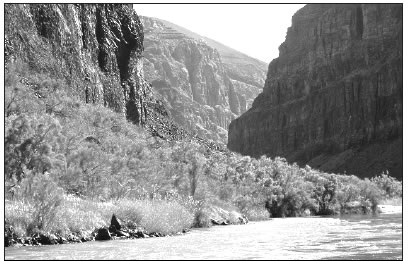

Tamarisk chokes out other vegetation along the Lower Colorado River in the Grand Canyon. Photo courtesy of Tamarisk Coalition

This story puts human folly and ingenuity up against nature’s ability to adapt and survive. It shows how a rare native songbird, a tiny beetle from Kazakhstan, and a shrub from central Asia respond to the human compulsion to control our environment.

As with many land-management efforts, this one has also spurred controversy, triggered a lawsuit and sparked a impassioned debate on how to best care for the natural world.

The tale begins in the early 1800s when the problem of bank erosion on Western rivers was “solved” by importing and planting the tamarisk shrub/tree, also called salt cedar.

Fast-forward 200 years, and the competitive tamarisk is considered the largest threat to riparian health in the West. It has crowded out the native willows, cottonwoods, sagebrush, rabbitbrush, and grasses. A tamarisk mono-culture chokes out all competing vegetation along rivers such as the Dolores, Mancos, Colorado, Gunnison, San Juan, Rio Grande, Green and Arkansas — as well as countless streams, arroyos and lakes.

Tamarisk beetles are small, but effective at controlling the fast-growing exotic plant. Photo by Dan Bean/Palisade Insectary

With roots up to 100 feet deep, the plant sucks down water-tables and springs and lowers river levels. It poisons the soil for other plants with its high levels of salt. Wildlife and livestock consider the leaves distasteful. Once-popular beach campsites are now filled in with the tall bushes. Movement along the shoreline through these thick forests is impossible, both for wildlife looking for a drink and humans casting a fishing line.

Add to that the fact that heavy stands of tamarisk are prone to wildfires, which destroy any native trees and shrubs remaining in the area. And the subsequent burnt litter actually stimulates the re-generation of the tamarisk.

For a time, the situation looked hopeless. Tamarisks are difficult and expensive to kill, seem to thrive on drought, and have no natural enemies. . . . that is, not in the Americas.

Arsenal of bugs

But then researchers looked overseas at the tamarisk leaf beetle (Diorhabda elongata), which is native to the Mediterranean and Asia, where it feeds exclusively on the local varieties of tamarisk, controlling their population halfway. So why not bring it here? asked American scientists.

In 1992, the U.S. Department of Agriculture gave approval for controlled releases of imported beetles on small test plots in the West. Ten years of additional study led to a widespread release program in 2001.

It’s been an effective tool for tamarisk control, reports Dan W. Bean, a leading author on the subject and director of the Palisade insectary of the Colorado Department of Agriculture.

“The results so far have been very good. In the places where the beetles have been for a while, like on the the Lower Dolores and Colorado rivers, the beetles have opened up the canopy, more sunlight is being let in, and it looks like the willow is making a strong comeback,” he said.

It takes 2-4 years for generations of the ladybug-sized beetles to significantly reduce a tamarisk forest. Thousands of beetles descend on one tree and eventually defoliate it. They spend the winter in the debris under the tree and emerge again in the spring.

On the banks of the Colorado River near Moab, Utah, the bug’s slow but steady work has turned the bushes brown, an astonishing sight to many used to the pervasive jungle of tamarisk crowding the campsites and shorelines.

The most remarkable attribute of this leaf-beetle is that it eats only tamarisk, and will starve if none is around.

“In the insect world it is considered a specialist that feeds on one plant,” Bean explained. “Not many things can eat tamarisk because it is bitter and salty. It’s pretty much poisonous to most native insects, but the tamarisk leaf beetle is highly adapted to it.”

A big concern of skeptics was that native vegetation would end up on the beetle’s menu. But extensive studies, as well as regular sweeps of release sites, so far confirm that the beetles are not eating native vegetation. They may land on native plants but they do not lay eggs or feed there, he said.

So-called host-range switching is not likely for the Diorhabda because if there were to be any crossover it would be to a closely related species of tamarisk, of which there are none here, Bean said. Just as in their native Kazakhstan, the bugs and tamarisk keep each other in check. As the tamarisk population wanes, so do the bugs who feed on them.

“They just become another leaf beetle in the ecosystem,” Bean said.

Nature’s irony

But there was a catch, as there always is.

The problem involves a native bird, the Southwestern willow flycatcher. Since 1995 the small bird has been listed as endangered (meaning extinction is imminent) under the Endangered Species Act, a status that gives special protection to its habitat.

The Southwestern willow flycatcher breeds in dense riparian vegetation along rivers, streams, or other wetlands. The vegetation can be willows, seepwillow, or other shrubs and smaller trees, but it needs to be dense and close to water.

The bird is down to an estimated 900 to 1,300 breeding pairs scattered across the Southwest, from southern California to western Texas. Its range includes Arizona, New Mexico, the southernmost part of Utah and extreme Southwest Colorado. It migrates to Central America in winter, returning to the Southwest in the spring to breed and raise young.

As tamarisk replaced willows along many waterways, biologists feared the worst, but they found that the willow flycatcher has adapted to nesting in tamarisk, which along with development and dams is blamed for the loss of 90 percent of the riparian habitat the bird requires to breed.

Along the Colorado River, 61 percent of flycatcher nests are now found in tamarisk, and 27 percent of its range is dominated by tamarisk, according to the Center for Biological Diversity. The nonprofit group estimates that the birds are spread out over 300 sites.

Recognizing that invasive tamarisk held some nesting sites for the flycatcher, the bio-control program criteria prevented releases of the tamarisk leaf beetle within a 200-mile buffer zone of known nesting zones. Researchers claimed the beetle would not do well in the southern climate where the flycatcher is most prevalent.

But they underestimated the beetle’s potential range and the human motivation to combat tamarisk.

“Under the Endangered Species Act, no harm can be done to critical habitat of the flycatcher,” explained Meredith Swett, a scientist with the Tamarisk Coalition, a riparian conservation organization based in Grand Junction. “The researchers believed the beetle would not reproduce well below the 38th parallel, but the beetles did manage to adapt to lower latitudes where the flycatcher is. That is problematic because it violates the Endangered Species Act.”

Then, in St. George, Utah, another problem arose. In 2006, local weed managers took it upon themselves to travel to a beetle release site near Delta, Utah, and collect some of the insects. They returned home and illegally released them into the Virgin River valley, a known nesting site for the flycatcher that lay within the 200- mile buffer zone. By 2008, the beetles were flourishing, reportedly defoliating a tamarisk with a flycatcher nest in it, and putting other nests at risk.

“It is too bad those people did that,” said Bean. “On the other hand, I think the beetles would have eventually made it there anyway.

“But it would have been better if the Utah folks had held off to give the Fish and Wildlife Service time to do some willow revegetation work there so the bird would have some place to turn to when the tamarisk was defoliated. It pushed the issue and made everyone quite nervous about the situation.”

It’s here

Locally, the tamarisk beetle was briefly released on a test site in McElmo Canyon in Montezuma County in 2007, county officials report. The yellow-striped bug has been spotted around Cortez, and there are significant numbers along the Dolores River from its confluence with the Colorado to just a few miles downstream from McPhee Dam, Bean said. Those beetles migrated upriver from release sites in the Moab area.

Through an agreement with the Ute Mountain Ute tribe, the Color-ado Department of Agriculture conducted a more substantial release on the Mancos River where it flows through the Ute Mountain Ute reservation.

“We had an agreement with the tribe that if the beetles arrived there naturally, we would help them with a release and monitoring,” Bean said. “We worked with the tribal council and their environmental center to do the bio-control on a really bad infestation of tamarisk along the Mancos River.”

The Ute Mountain reservation is within the 200-mile off-limits zone for the beetle because of potential willow flycatcher nesting sites in northern New Mexico, but “we made the exception with the tribe because they are their own entity, they wanted it, and they already had beetles on their land,” Bean said.

Control by beetles works well in remote, inaccessible areas such as lower McElmo Creek, said Don Morris, Montezuma County weed supervisor.

“Tamarisk there blocks drainages, and it is expensive and labor-intensive to try and get in some of these places and control it manually,” he said. “We’ve seen some success, but there are some unknowns.

“In theory, if the beetles run out of tamarisk they will starve, but in five years or 30 years, who knows? They might get hungry enough and revert to eating other plants.”

At the request of the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service, scheduled releases by the U.S. Agriculture Department of the tamarisk beetle in western Colorado have been halted to protect the willow flycatcher thought to be in northern New Mexico. The beetle will continue to be introduced in other parts of the state, especially along the tamariskinfested Arkansas River.

“There will be no more releases in western Colorado, due to the flycatcher, but I think the beetle will continue to move naturally into your area,” Bean said. “We will continue to monitor that area and if we see patches of tamarisk defoliation we will alert locals to it.”

Restoring the balance

Another challenge facing the tamarisk bio-control program is revegetation with native species after the tamarisk has been killed by the beetle.

In some cases, river areas include native species alongside tamarisk, giving them a good chance to re-establish once the tamarisk is reduced. In other cases, active restoration programs will be needed.

“For it to be successful, the beetle release must be followed be re-vegetation as soon as possible. Otherwise, the control technique will end up destroying habitat for wildlife and then put stream banks at risk for erosion,” said Stacy Kolegas, executive director of the Tamarisk Coalition. “We’re not real sure how native plants will respond. If they don’t take off we will need to actively help restore them.”

Another problem is that pioneers who brought the tamarisk here failed to record what was there originally, explained Montezuma County’s Morris.

“So now we don’t exactly know what to go back to, because there is no record there,” he said.

Researchers have had to rely on old photographs to try to determine what was historically present. Interestingly, many places where tamarisk now flourishes were devoid of vegetation 150 years ago, a testament to the adaptive nature of tamarisk, growing where no native plants could survive.

Revegetation programs are just beginning to take shape so it is too early to claim the bio-control program is a success for native flora and fauna.

“It may be a good thing in the long run for the Southwestern flycatcher because tamarisk will be replaced with willow and other native species,” surmised Swett, of the Tamarisk Coalition. “In the short term, however, there could be losses of birds.”

Filing suit

That’s unacceptable to the Center or Biological Diversity and the Maricopa (Ariz.) Audubon Society. They have filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for “indiscriminate introduction of the tamarisk leaf-eating beetle into critical habitat of the southwestern willow flycatcher,” according to a March 27 press release.

The environmental groups hope the suit will force modification of the beetle program and increased habitatrestoration efforts.

“We face loss of the flycatcher in the Southwest because APHIS has broken its promises and refuses to take responsibility. We must now appeal to the courts to help us save this adorable little migratory songbird,” said Robin Silver of the Center for Biological Diversity.

“The law requires that all federal agencies consult with the Fish and Wildlife Service when their actions jeopardize a federally protected species,” added attorney Matt Kenna of the Western Environmental Law Center, representing the plaintiffs.

The divisiveness over the bug, the bush and the bird will undoubtedly continue. For purists, it seems nonsensical and risky to combat an exotic species by introducing another one. For land-managers battling a highly invasive species, the beetle program is a practical solution with acceptable risks.

“Both sides tend to the extreme,” Swett said. “Some think the beetle will eat all the flycatcher habitat and it will be catastrophic. On the other side, the beetle’s movement is a patchy, slow process that will gradually give more room for native plants.”

The middle-ground solution seems to be enacting aggressive plant-restoration programs where tamarisk has been eliminated.

“The real key is getting native vegetation re-established, and I think that will ultimately benefit the flycatcher, more than having a tamarisk monoculture,” Bean said.