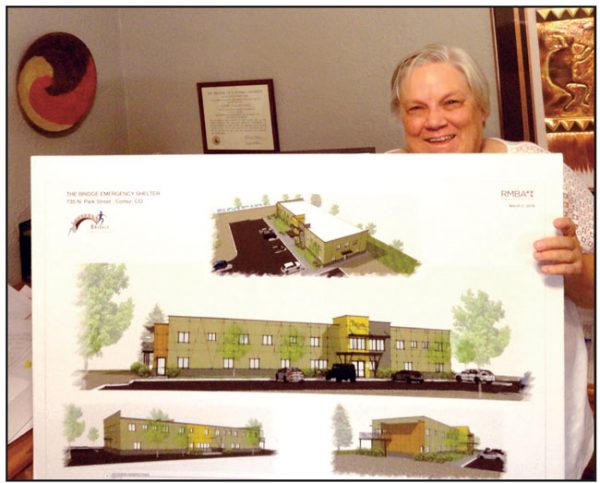

Laurie Knutson holds architectural plans for the new Bridge Shelter. It will offer transitional housing on the second floor in addition to emergency shelter on the ground floor. Photo by Sonja Horoshko.

The Bridge Shelter in Cortez is breaking ground Thursday, Sept. 6, at 9 a.m. on construction of a $2.3 million shelter in Cortez. The new building at Empire and Park streets near the new Montezuma County Combined Courts building and Osprey Packs headquarters, is conveniently close to Centennial Park, Southwest Memorial Hospital, and one of the two soup kitchens that serve a hot lunch to many of the same clientele six days a week.

The shelter offers emergency housing to a core group of about 20-25 people seven days a week, October through April, says Bridge Executive Director Laurie Knutson, and October is just around the corner.

The complexity of city and county approval for the project has delayed the schedule three months, causing concern that the homeless people seeking assistance will be put at risk of hypothermia and death outdoors this winter.

Volunteer nucleus

The Bridge Shelter was founded in 2006 by an entirely volunteer staff after years of individual care was offered to vulnerable people who had nowhere to go at the end of the day. They were stranded and sleeping outdoors around the perimeter of the city in the winter.

The need was great in those days, and it hasn’t diminished. Today, the professional growth of the Bridge and the services they offer guests has increased the staff to 13 paid employees, in turn supporting 13 families in the community.

During the past 12 years the shelter assisted 3,053 guests. Programs that encourage people to move toward independence are a top priority at the Bridge. The shelter offers everyone referrals to case-management services and substance-treatment programs while collaborations with other local organizations support the Bridge effort to offer more than the basic need for showers, a free laundry, a bed and two meals.

The day-labor program connects workers with temporary jobs while collaborations with the Piñon Project and Axis Health System offer access to physical and mental health care, child programs and family support. And it’s paying off for some of the working poor who utilize the shelter, as the number of guests working full or part-time has increased in recent years.

As a result, Bridge statistics are staggering. Over the years they have served 48,926 meals during 97,852 nights of stay.

Fresh start

The board and Knutson identified the need for a new, permanent building when the Bridge lost its long-time home in the former Justice Building at the northeast corner of Centennial Park. They used the loss of their permanent space as a challenge to expand housing access for the people and community the shelter serves.

By January 2018, the vision for the new shelter had taken shape. They contracted with Michael Eberspacher, RMBA Architects, Durango, to design a building that serves the temporary, overnight emergency clientele but also implements a transitional-housing phase in support of those clients who are working toward independence in the community.

The new plan for the first floor provides emergency shelter for 26 people, a sobering space for up to 15 people, day-labor facilities and office space. Total temporary emergency beds on the ground floor will house 41 people 18 and older.

The second floor provides transitional housing, rented at a very modest rate to 24 formerly homeless, qualified clients. The one- and two-bedroom apartments will generate income to offset costs of sheltering operations.

The facility is the first of its kind in the state of Colorado that includes sheltering, labor opportunities and transitional apartments under one roof.

Roomies

Renter/clients will be sharing the spaces with roommates, explains Knutson. “To other people, it may seem like an inconvenience to share a space with another formerly homeless person, but the opportunity will stabilize people who are trying to land affordable housing and a job in Cortez. It becomes an incentive.

“To live in a secure environment where a person has access to internet communications, is able to learn about job mobility, connect with programs designed to support their needs, socialize, and share responsibilities dignifies a person, helps them feel that normalcy is possible again,” says Knutson.

“When they qualify for the program I’ll tell them to go buy an alarm clock, something homeless people don’t have need of when they are living on the street.”

The Department of Local Affairs committed $1.9 million to the project while the Gates Foundation granted $80,000 toward construction. The remaining monies have been raised through matching donor-campaigns and community fundraising drives. “We’re offering a natural transition to the nearby low-income Cortez Apartments,” explains Knutson, the next step in low-income housing.

The project is capitalizing on innovative, inclusive design objectives targeting dignity as a restorative force that can help a person cope with the crises of seeking emergency shelter. The building will continue to provide emergency shelter, day-labor and collaborative case management opportunities. It is a stepping- stone program that can potentially stabilize a client, and increase job retention, improve income and emotional strength.

Knutson says the shelter board chose to include transitional housing in the design requirements because it directly addresses the U.S. affordable-housing crises that Cortez and Montezuma County now face.

Global and local crises

The clients at the shelter are often newly homeless. People find themselves without the ability to earn enough money to rent on low-income wages. Affordable housing is a global issue, Knutson explains.

“The people are not the crisis. Housing is the crisis. Minimum-wage jobs coupled with cost of living and rent increases are impacting the need for emergency shelter. People are having a hard time making ends meet in a market prime for real estate investment and profit.”

CBS recently reported that although unemployment is at record low levels in the U.S., income levels for low-wage earners are not rising and as a result 10 percent of the population suffers from food scarcity. That leads to health and work issues, stagnating income mobility, and puts low-income earners at risk of homelessness.

In August, 2018, New York City and State reporter Ben Adler wrote that homelessness truly is a housing problem.

“Once the homeless are indoors and safely out of any rich person’s sight, public interest in what becomes of them evaporates. But most homeless … are not subway panhandlers or other avatars of the stereotypical mentally ill or drug-addicted beggars and bag ladies. The major increase in homelessness is among people who simply lack a place to live and wind up in a homeless shelter.”

Even for people with other risk factors, homelessness could often be averted if they had affordable housing. “It’s not a homeless crisis; it’s a housing crisis,” said Sam J. Miller, a spokesman for Picture the Homeless. “There are plenty of mentally ill people who have housing; there are CEOs of Fortune 500 companies who have substance-abuse problems. It’s still about whether you can afford housing.”

Knutson agrees. People lose their apartment or home and sleep on couches at friends or relatives for a month or two. Eventually they have to move on. Often they share living costs, like food and electric bills, and pitch in for rent if they have a job, she explains. Many are saving to get back into a place of their own, but the homeless circumstance opens the door for other problems, like depression, drugs, alcohol and abuse.

“It’s tough in Cortez, where rents can cost 67 percent of a minimum-wage income,” she says. “It’s very hard to stabilize your own housing, which is the first step. You can’t get ahead. If you are evicted then the problem intensifies because after that most landlords won’t rent to you.”

According to Archdaily.com, a professional news site for architects and designers, housing investments today are becoming a means of accumulating wealth rather than fulfilling the fundamental goal of shelter.

In Cortez, notes Knutson, investors are acquiring houses at very low costs, doing some basic cosmetic renovations and then renting for $1200-$1300 a month. No homeless or low-income family can afford first and last month’s rent and a deposit in such a market.

“People of some means are moving here, growing an upscale community, which overall is good for the town, but meanwhile the cost of rent and living increases.” It becomes harder to get traction and move out of a poverty cycle.

Barriers

The bridge is a low-barrier shelter, the only one in the five southwestern Colorado counties. They rarely turn people away. The staff is trained to recognize signs of a health crisis, clues about drug use. They are educated in conflict-resolution and harm-reduction techniques. There are very few criteria for accepting people in the emergency shelter.

As a result, many people come from other high-barrier shelters where they aren’t admitted, such as the Veterans of America shelter in Durango where they set higher admission requirements, such as no inebriants or people on drugs.

Before the Bridge Shelter organized, Cortez Police Chief Roy Lane, his wife and a handful of volunteers collected blankets, gloves, hats, and winter coats, and delivered them to people living outdoors in the canyons or sleeping under the sagebrush around the town during winter months. He knew where to find them. They were regulars.

There was a core group of about 20 to 25, says Lane. It was mostly a Native American population back then, 20 years ago, but now there is an increase in Anglo people in need of emergency shelter.

For many minimum-wage workers, life is about hand-to-mouth survival. They have little to show for their labor. They are often forced to make choices between food or medicine, walking to work or riding a bike rather than owning a car.

In spite of their efforts, they remain vulnerable, especially to eviction that often leads to homelessness and a need for emergency shelter — with a place to store belongings, a shower, a bed, a private place to think, a warm meal, and emotional help.

Winter of risk

Overbuilding to meet city codes, such as a last-minute need to design for a required drinking fountain on the second floor of the new building, created delays in the new shelter’s construction schedule, which then increased its costs, says Knutson.

“Current construction costs are rising by 15- 20 percent across the country due to the federal tariffs on buildings materials today, and we’re feeling the effect of that.”

Although the Bridge has secured more than $185,000 from local foundations, businesses and community members they are now seeking an additional $100,000 to cover final construction costs. A recent $40,000 challenge grant has been offered to help meet the overruns with a fundraising campaign beginning at groundbreaking.

Weeminuche Construction is contracted to build the shelter. Construction is expected to be finished by Spring 2019.

Meanwhile, the construction delay may have put shelter clients at risk this winter. The Bridge is working to locate temporary shelter for this coming winter. At press time negotiations with landowners were pending approval by the city.

However, the process could take until the end of October, meaning the shelter would not be able to open on time.

Additional options for immediate sheltering are few.

The homeless in the community are more mobile today, offers Lane.

“And, in my opinion,” he says, “most of the homeless do have homes somewhere. Home for at least some of the Native American population is close-by. I have been in law enforcement for 37 years, always in border towns around the reservation.

“Over the years I have seen people repeatedly come looking for their family members. They come to pick them up and take them home.”

The issue is not only a family issue, but a tribal one. “Over the years we have tried to work with the surrounding native governments, like the Navajo Nation,” he said, “to develop a program where they could get their people back home. Unfortunately, we have not been successful in our attempts to solve this dilemma.”

Knutson said the shelter expects about 40 people this winter, of which about 80 percent are usually male, “and there are always new people who stay two to four nights and then move on.

“People often assume these people can’t take care of themselves, when, in fact, they certainly can and it’s empowering to provide ways they can take charge of their own lives.

“Just because our building has been delayed doesn’t mean the need isn’t going to be there in October. We need to prepare for them.”