In the late spring of the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, as catastrophic drought warnings began looming across the western United States, I received in the mail an edited collection of poetry and prose written “to speak love to water.” It could not have come at a better time.

WET: An Anthology of Water Poems and Prose From the High Desert and Mountains of the Four Corners Region is available at Cliffrose Garden Center, and Cliffrose on Market, in Cortez, as well as Absolute Bakery in Mancos, Colo. For more information about ordering online, contact Laurie Hall at info@montezumafoodcoalition.org, memo line WET INFO.

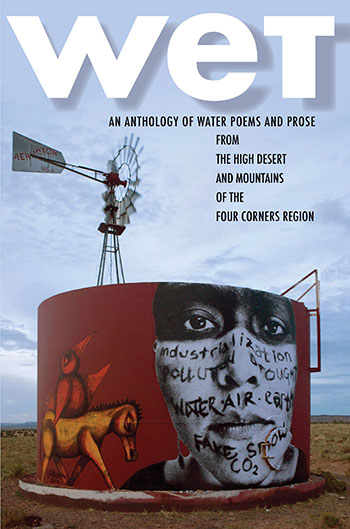

WET: An Anthology of Water Poems and Prose From the High Desert and Mountains of the Four Corners Region is a comprehensive volume, the product of a collaborative effort spanning the Four Corners region. Spearheaded by editors Gail Binkly, Sonja Horoshko, Renee Podunovich, and Native American Literary Liaison Michael Thompson (Mvskoke Creek), WET is published by Laurie Hall at Sharehouse Press, a project of the Montezuma Food Coalition.

The first in a four-volume series, WET is a project, in Horoshko’s words, of creating “anthology from the earth up.” This remarkable book speaks with many voices, Native and non-Native, and in five languages: English, Diné, Spanish, Mvskoke Creek and the language of the Haak’u Acoma. Each of the 30 contributors writes from their particular angle of vision, creating an axis of literary water energy trickling from the Rocky Mountain snowpack surrounding Telluride, Colo., through the dry land watershed and the town of Cortez, into the tribal lands of the High Desert region. The writing evokes many different ways of knowing water, places, and greater-than-human communities over time and across space, sharpened by the contemporary scarcity of water in the region, and made reverent by the care that scarcity demands.

WET opens with Haak’u Acoma activist and writer Maurus Chino’s “Swimming in Clouds”: a series of journal entries documenting morning walks to visit the river near his current home in Albuquerque, and the events and memories these walks reveal. Originally published to social media in the first spring season of the pandemic when many of us were hunkered down under stay-at-home orders, Chino’s entries are generous, written to share the river with others. He names the pair of wood ducks he often sees there, describes the reflection of the sky on the water, recounts the Chuna, a stream that flowed near his home in Ak’u. Some entries end with his urging to “Make this day a good day. Be safe,” and so it is with this feeling of care and attentiveness that the reader is launched downstream into the poems, prose pieces, and essays that follow.

The theme of making journeys to water in arid landscapes — and the knowledge and labor necessary to locate it and bring it where it is needed — are major currents in this volume. They run through L. Luis Lopez’s delightful poem on his grandmother’s instructions for bringing water from the ditch to nourish her flowers, “Fifteen trips it always took.”

Ed Singer (Diné) offers the reader a meditative piece on his childhood trips to a hidden spring in a canyon near his family land at Gray Mountain, “Under the Rock at Tséyaa Tóh,” where his family stored a shovel, a bucket, and fixings for tea and coffee. The water in the spring “was chilly, delicious and clean,” and every year the Singer family rebuilt the sweat lodge “with debris deposited during the runoff, the same that swept away the one we built the year before.” Tséyaa Tóh is also the Navajo name for the town of Cortez.

In Tina Deschenie’s “My Take on the Water Rights Settlement,” and researcher Dana Powell’s “Riparian Sensibilities,” themes of water access raise questions of environmental injustice on the Navajo Nation, where generations of coal and uranium industry have depleted and contaminated precious water sources. Deschenie (Ta’neeszahnii, born for To’aheedliini) recalls herding sheep to a windmill near her home as a young person, but being forbidden to drink that water herself; for drinking water, her family brought tanks to a public well. “Trying hard as I might I don’t ever remember seeing any White people parked in line at the water well back then even though we lived in the Checkerboard Land area… Were we Navajo the only ones hauling water back then and even today still?”

These deep understandings of scarcity underscore the joyful, describing times of abundance, rituals of renewal, and possibilities for growth, change, and justice.

David Feela writes that “When rain falls in the desert/ fragrance flash-floods the senses/unbraids itself like a garland/compelled to become a garland.” Gail Binkly recounts the life cycle of spadefoot toads, who can mature in as little as two weeks, making use of small, intermittent pools formed after sudden rain.

Renee Podunovich describes feeding blossoms to the Dolores, “River of Sorrow,” and finding there an experience of mercy and evidence of constant momentum and change.

There are dozens of extraordinary authors and pieces in this book. I urge you to obtain a copy and encounter its richness for yourself. This is a collection for people who love the Southwest, and for people who care about interdependency, about the ways our lives and places are tangled together.

I live in the Pacific Northwest, a guest on lands the Duwamish, Suquamish, and Muckleshoot have called home since time immemorial. This is a region defined over millennia by its abundance of water, yet as I write this review, record heat waves are buckling the highways, heating the rivers, and endangering the next generation of salmon.

In this era of climate change and global pandemic, spurred on by the rapacious, entwined systems of colonialism and capitalism, we would all do well to spend time thinking about the importance of water and relation.

I look forward to introducing my students to this volume, and the forms of story and wisdom these Four Corners writers have so generously committed to the page. “Be safe. Do your best,” as Maurus Chino entreats us.

Sarah Fox is the author of Downwind: A People’s History of the Nuclear West (University of Nebraska Press 2014, paperback 2018). She is a Killam Doctoral Scholar and a Ph.D. student in history at the University of British Columbia. Her current research examines the contested terrain of ecological restoration, remediation, and environmental justice in the Pacific Northwest, and the way these projects engage (or ignore) Indigenous sovereignty and local, experiential knowledge about histories of environmental change.