The residents of Cameron, Ariz., a chapter in the Navajo Nation Western Agency near the Grand Canyon, feel a little like David with his slingshot.

Armed with only a humble weapon – a local community initiative to develop a wind farm in their own back yard with the developers they trust – they face forces that are daunting.

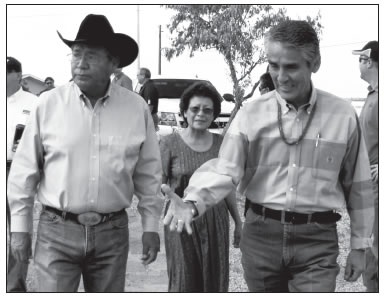

Navajo Nation president Joe Shirley (right) arrives at Cameron Chapter in the Navajo Western Agency to tour the site of the proposed community-initiative wind farm on Gray Mountain, Ariz., with Ed Singer, Cameron Chapter president, on Aug. 3, 2009. Shirley must decide whether to sign or veto legislation to move forward with the wind farm. Photo by Sonja Horoshko

During the past four years, multiple Goliaths have charged over the steep, rocky reservation canyons assailing Cameron’s resolve, challenging the community’s right to development control and revenue return on their project. The latest opposition is, surprisingly, the Navajo Nation central government, the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority, a non-profit Navajo Enterprise, and the forprofit subsidiary, NTUA Wind, Inc.

At stake is the revenue return to the Navajo Nation and ownership of the project.

By the beginning of summer 2009, International Piping Products, a company based in Texas and chosen by Cameron officials to work with the chapter, had finished the oneyear feasibility study needed to determine the wind capacity on Gray Mountain near Cameron. The chapter was poised to launch a 500-megawatt wind farm to jump-start economic development in the impoverished community.

But bureaucratic delays in the Navajo governmental process and interference by outside developers eager to get in on the wind-farm potential hampered the project, and it began to fall behind the schedule the chapter had worked out with developers Bruce McAlvain of IPP and the management team of Sempra Generation, a renewable- energy company developing large-scale projects throughout the southwestern United States.

One giant step

Sensing a gridlock when negotiations stalled, the community reached out for help from other chapters. Over the past 18 months they have built a strong alliance focusing on other Western Agency delegates. Using the network to lobby the Navajo council, they worked hard to keep them informed on the progress of negotiations and the time frame so critically impacted by delays.

Meanwhile, IPP launched ad campaigns drawing attention to the delegates’ opportunity to “clear the air” for future Navajo grandchildren.

Then, on Oct. 21, the Cameron Community wind farm took a giant step forward toward reality. The Navajo Nation Council passed a bill 41-23 to approve land-lease negotiations between Sempra Generation /IPP and the Navajo Nation for the development of a wind energy project on Gray Mountain. It was sponsored by Raymond Maxx and Bobbie Robbins, council delegates from the Tóh Nanees Dizí /Tuba City Chapter, and Jack Colorado, Cameron Chapter delegate.

Mitch Dmohowski, director of development for Sempra Generation, answered questions and explained details of the Sempra / IPP proposal after Ed Singer, Cameron Chapter president, addressed the council delegates in Navajo.

Singer later told the Free Press, “I used creativity to describe our process and our need to work together. In Navajo there is no word for ‘art’ per se, but many activities can be described as creative. The most obvious is the activity of drawing – how my community, in seeing their own needs, is creating the beginning of a drawing.”

Singer told the delegates it was time for them to collaborate and finish the drawing by making their mark with a yes vote. He also reminded them that four years ago the Western Agency, 18 chapter delegates and chapter officials, had passed a resolution 63-0 in support of the Cameron Chapter resolution to build the wind farm.

Council delegates debated the legislation discussing Navajo employment, job creation, revenue to the communities and the central government and ownership. But soon a chant came from the floor, “Vote! Vote! Vote,” and Speaker Lawrence T. Morgan called for the delegates to cast their votes.

Now the tribe waits to see whether President Joe Shirley, Jr., will veto the legislation.

‘A top-shelf deal’

The historic vote came after years of hard work by Cameron Chapter officials. When the project became bogged down, they began inviting officials from their central government to visit the site and people. None responded at first. And so it was a hopeful sign when Shirley finally agreed to come to the chapter on Aug. 3, 2009.

“I took President Shirley on a Maverick helicopter tour where the wind farm will go in on Gray Mountain,” said Singer. “That same day he said he strongly supported the wind farm and Cameron community.”

Accompanying the president to the discussion that day was Navajo Attorney General Louis Denetsosie, whose son, Warren Denetsosie, “is the legal counsel for NTUA,” Singer said, adding, “How’s that for conflict of interest?”

Jim Sahagian, a Sempra director of the Gray Mountain project at the time, sat directly across from Shirley while he told Sahagian that Sempra was “to negotiate with NTUA and to come back to him in his office if negotiations got problematic,” Singer said.

The gauntlet was down. Negotiations for control of the project began with NTUA as Sempra put the deal on the table. Sempra offered to fund the entire $1.5 billion upfront costs of development and construction. At the end of that phase, the Navajo tribe would be able to buy in at 20 percent equity for that percentage of the cost of the project at that time.

No tribal investment money would be needed to build the project.

Sempra projected a 24-month construction schedule that would take the energy to connection on the transmission lines when the 250 turbines are operational.

“It’s a top-shelf deal,” said McAlvain. “Even if the nation puts no money at all in the project, they are guaranteed 20-year minimal lease revenues of 3 percent of gross to central government, and 1 percent gross to the local community – paid first, before anything. If the nation chooses to invest in 20 percent equity ownership of the project at the end of construction, we will welcome their partnership.”

Translated into cash for the tribe, “3 percent is $3.7 million a year or $74 million over 20 years with no investment, an infinite return,” said Dmohowski of Sempra Generation. “The local community will make $26 million over 20 years.”

This lease revenue could make it possible for the Cameron Chapter to buy into an equity position for themselves without the help of Navajo central government.

51/49 or 80/20?

NTUA counter-proposed with 51 percent NTUA tribal ownership / 49 percent Sempra. The model, referred to often as an “51/49 mantra,” came from the negotiating NTUA was doing at the time with Mission Energy and Foresight Wind Energy to partner in a much smaller, 85-MW utility-scale wind farm on Big Boquillas Ranch land near Seligman, Ariz.. The preliminary partnership structure was needed for the council legislation that, if passed, could clear the way for the lease and financing agreements to develop the renewableenergy project now called “Big Bo.”

Tribal equity obligation is 51 percent of the estimated $150 million price tag to build out the first phase of Big Bo. The project was scheduled to begin construction in December 2010 and be completed a year later. In order to reap the benefits of investment tax credits, the NTUA board of directors authorized formation of a for-profit subsidiary, NTUA Wind, Inc., that can develop, finance, construct, own and operate the Big Bo wind farm. NTUA Wind, Inc., will control and manage 51 percent of Boquillas Wind, LLC, while Mission Energy and Foresight Wind Energy, the experienced partners in the deal, will own 49 percent.

Big Bo lease revenue for the tribe is split, with 0.5 percent of gross to NTUA and 3.5 percent for central government. Because Big Bo is located on fee simple land and no people live there, no percentage goes to benefit a local community. Thus, Cameron officials say there is no comparison between this deal and the Cameron community initiative project.

By the time the Big Bo legislation passed in January 2010, press releases predicted that the shovel would be in the ground December 2010. The latest NTUA flyer passed out on Oct. 21 to council delegates at the morning caucuses stated that the turbines will be bought by Dec. 31, 2010.

Gross or net?

Michael Connolly Miskwish, a natural resources and energy consultant with Laguna Resource Services, Inc., and a graduate student in economics, is a member of California’s Campo Band of Kumeyaay Indians. In 2005, his tribe put up a 50-megawatt wind farm on their 25-square-mile tribal land base. They are now expanding their wind farm with another 160 megawatts, hoping to complete construction in two years. The Campo tribe has gained experience as well as revenue from the first phase of their wind farm and will now be an equity owner in the expanded project.

“Sometimes the more ownership you have, the less royalty money you make. There are ways to structure,” Miskwish said. “Sometimes getting a percentage of the gross might be more than a percentage of the net as an equity partner.” The tax implication in each project is also crucial, “especially state taxes paid to states instead of to the government where the land is located, like tribal land.”

In a paper published with the American Bar Association’s Native American Resources Committee Newsletter, “Capturing the Full Benefit of On-Reservation Renewable Energy,” in November 2010, Miskwish wrote, “Tribal economic development has long been hampered by the infringements of state tax policies onto Native lands.

“Renewable energy holds a tremendous promise for tribal communities across the nation. Yet, current policies are hamstringing tribal development and putting them at a competitive disadvantage … Federal help in limiting state encroachment into tribal economies is desperately needed in many areas, but nowhere is it as clearly unfair and regressive as in the commercial wind/renewable energy sector.”

One line item rarely exposed to the public is the construction payroll. For the Gray Mountain project, construction is expected to generate 400 jobs, a mixture of full- and part-time employment in a community where the 75 percent unemployment rate hasn’t changed for a decade and 38 percent of families live below the poverty level. The construction jobs will flood Cameron with paychecks that could approach a million dollars a year in Navajo-preference construction- worker wages.

Getting the project up and running is critical to producing economic benefit for the Cameron community. Delays have stalled the project now for more than three years. “NTUA has put a stop to negotiations by sticking to one position,” said Singer. “To negotiate in good faith you must disclose your limitations and they haven’t done that. When they did reply it was always the 51/49 mantra and no less.”

‘The clock is ticking’

Now that the legislation has passed the council, it must go to President Shirley and his team of advisors, which includes Chief of Staff Patrick Sandoval. The Free Press met with Sandoval at the Tuba City District Court on Oct. 28.

Sandoval said the president gets a 10-day review period on every bill. During that time his staff reviews the legislation and refers it to the president for his approval or veto. “He uses all 10 days,” he said, “before announcing a decision.”

However, Sandoval, said in his opinion, “The Sempra / IPP offer is not a good deal for the Navajo people, I mean all the Navajo people. How much more money goes to the developers?”

He questioned Sempra’s ownership structure of the wind farm, adding that, “the developers have not given enough benefits to the local community like other projects have.”

But according to McAlvain (Choctaw / Irish), director of the IPP feasibility phase of the project, “We worked for three years identifying immediate needs that we could help with in the community.”

High on the list are the septic tanks and 12 stock dams IPP repaired, he said, “and more than 50 trips hauling water to the elderly and disabled, and wood to the chapter. There is always something to do there, some assistance needed.”

President Shirley was also in Tuba City District Court on Oct. 28. He told the Free Press that he hadn’t received the Oct. 21 legislation yet and that he generally doesn’t announce his decision until the full 10 days is up.

George Hardeen, his spokesman, confirmed that procedure, “unless,” he said, “there is a public signing ceremony, like our casinos or uranium bans.”

In a follow-up telephone conversation a day later, Hardeen said the legislation had come over to the president’s office. “The clock is ticking.”

Sempra has over 2600 megawatts of operating projects in Arizona, Nevada and California. According to Dmohowski, “the company has signed renewable-energy power purchase agreements with three California projects and is in advanced negotiations with other Southwest additional wind and solar projects. The huge Gray Mountain wind energy project can be operational in 2013. “

Delays at this time are critical for any renewable-energy developer because the market for California and Arizona utilities is dwindling as they reach their portfolio targets and transmission space is taken up by other regional projects. “Normally it takes less than three months to secure a lease with a typical landowner – Gray Mountain wind has taken over three years and counting,” Dmohowski said.

Passage of this legislation was critical to the timing of the project, “IPP/Sempra had to stop spending on development until legislation had passed council sustaining the possibility of securing a lease with the Navajo Nation,” said McAlvain.

Robbins, co-sponsor of the legislation, knows that Shirley favors the 51/49 NTUA structure that locks out the people of Cameron, who feel that NTUA is not concerned with their best interests and does not have the collective management or skilled experience of the Sempra/IPP developers.

“If the president vetoes the legislation, we will vote to over-ride before our terms are up and the new 24-seat council is in place,” Robbins said. “This council finally understands the Sempra deal and really wants it. We’re all looking down the road 20 years from now at the positive change we made for our people in this session. Sempra’s proposal is straightforward and a much lower risk to the novice Navajo Nation renewable energy ventures. Sempra/IPP has a much higher probability of success in actually getting a project built.”

Delegate Key Yazzie Mann, K’ai’bii’tó, voted yes on the legislation. Walking out of council chambers, he felt proud to be with the Cameron wind-farm team. “This was a vote for the local people, finally.”