There was a sense of déjà vu about it all.

During a grueling, six-hour public hearing on Jan. 12, the Montezuma County commissioners listened to pros and cons — mostly cons — about a proposed asphalt operation near Mancos.

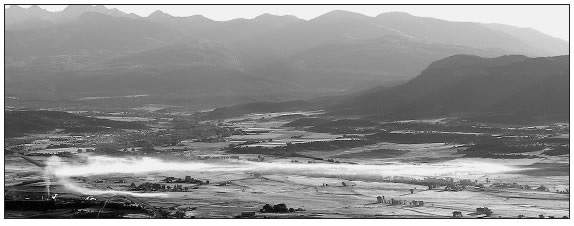

A plume of smelly emissions stretches across the Mancos Valley in July 2007 from an asphalt operation. On Jan. 12, the Montezuma County commissioners approved permits for a different asphalt plant in the same area, but this one is not expected to make the same smelly type of asphalt. Photo by Tom Vaughan/Fe Va Photos

Twenty-six people spoke against the asphalt plant, and five of them also read letters from other citizens opposed to the plant.

Three citizens spoke in favor of the project, two of them sons of the engineer who is working with Four Corners Materials, the applicant.

But, in the end, the comissioners came down in favor of jobs and industry, voting 3-0 to grant high-impact and special-use permits for the plant.

“If we don’t do it in one person’s backyard, we’ll do it in somebody else’s backyard,” said Commissioner Larrie Rule (who is now the chair of the commission).

Commissioner Steve Chappell seemed disturbed there had been such opposition to the proposal.

“It seems every time something comes along that would help the economy, we have a loud outcry,” he said. “I think we have to be careful about destroying the economy and making this just somebody’s playground or retirement area.”

Rule, too, emphasized the importance of jobs. “Not do anything in Montezuma County any more? Do nothing? No jobs? Is that what you want to hear?” he asked the audience.

Commissioner Gerald Koppenhafer cited the county’s need for asphalt. “Montezuma County uses a lot of asphalt to blade-patch our roads,” he said. “We’ve hauled a lot from Farmington, because they are the only ones producing it, and it takes a lot of money. Hopefully this will help the situation.”

But the audience, which had dwindled to a handful by the end of the torpor- inducing marathon, was not persuaded. Several people asked whether the commissioners were even listening to what was said.

“We do listen to people,” Rule responded, “but we still have to listen to the whole county.”

It was a familiar scenario. In the past two years, the commissioners have held several public hearings related to gravel, asphalt, similar industrial/commercial development, and land-use code changes to facilitate industrial-type operations on ag land. In nearly all those cases, despite a parade of speakers opposed to the proposals, the commission has voted to approve them.

But, as Rule noted, the county as a whole appears to have a different slant on things than the people who oppose such projects. Rule and Koppenhafer both won re-election handily in 2008, running against opponents who advocated stronger land-use planning.

In this instance, Four Corners Materials, a company based in Bayfield, Colo, but part of a much-larger corporation, sought permission to operate a hot-mix asphalt plant on property at 39238 U.S. Highway 160, just west of Mancos. Four Corners had already received permits for a gravel pit at the same location, despite neighbors’ opposition.

When granting the permits, the commissioners stipulated that there will be an annual review of the permit and that the company must notify the county if it plans any projects that could exceed limits on air pollution.

The latter stipulation was a nod to neighbors’ concerns about the smell in the summer of 2007 that emanated from an asphalt plant at the nearby Noland gravel pit. In that case, Kirtland Construction was creating a special (and odiferous) type of asphalt, required by the federal government, for a paving job at Mesa Verde.

The county shut that asphalt operation down because it had no county permit, though not until after Kirtland had completed the Mesa Verde job anyway. The owners of the Noland pit then sued the county, saying they shouldn’t need a high-impact permit, but they lost their suit.

The Jan. 12 decision seemed to portend another possible lawsuit against the county, though from the opposite point of view.

In a Nov. 17, 2008, letter to the commission about Four Corners’ asphalt proposal, Durango attorney Jeffery Robbins, representing four landowners near the pit and asphalt plant, said the neighbors “strenuously object” to the proposal.

Robbins said they recognized that the board in July 2008 had changed its land-use code to specifically allow gravel pits and asphalt plants on agricultural lands if permits are obtained.

“My clients do not agree that this change makes sense from a planning perspective,” Robbins wrote. “Quite frankly, if a High Impact Permit procedure can result in industrial and incompatible uses throughout the County, there is no reason for this Board to have zoning at all.”

However, he wrote, even if those changes are accepted, the proposal for the asphalt plant does not meet the criteria set forth in the code because it would “essentially change the neighborhood’s character from its present rural, agricultural nature to one that is commercial or industrial.”

Robbins cited other objections to the proposal and concluded, “. . .these proposed industrial uses cannot be approved by the County because they run afoul of the protections of the zoning code. . .”

Montezuma County was sued successfully over its 2005 approval of a gravel pit on ag lands and its 2004 approval of a warehouse expansion near Mancos. However, those lawsuits occurred before the county adopted its new regulations allowing certain industrialtype activities on ag lands.

Robbins’ firm of Goldman, Robbins and Nicholson was the counsel in both those successful lawsuits.

At the Jan. 12 hearing, neighbors voiced a variety of objections to the asphalt plant, focusing on emissions of pollutants, safety issues related to increased truck traffic, and quality-of-life concerns about dust, noise and lights.

“It’s unfair to make us pay for their economic advantage,” said Mancos Valley resident Dave Sipe. “Why not have the mobile asphalt plant where the project will be? At Mesa Verde or wherever? I haven’t heard of any future paving projects in Mancos.”

Another resident, Sarah Staber, commented, “There isn’t much reason to move to the Mancos Valley except that it’s remote, quiet and pretty. You take away a lot of reasons to move there.”

But Peter Kearl, resource environmental manager for Four Corners Materials, noted that the company has a good reputation and said it does not want to do anything to cause problems for neighbors. The asphalt operation will create three jobs, he said.

He added, “Without paved roads, travel would be much more difficult and dangerous. . . and the quality of life would be clearly diminished if we could not have goods brought to us over paved roads.

“Plants that produce hot mix have to be somewhere,” Kearl added. “They can’t always be in someone else’s backyards.”