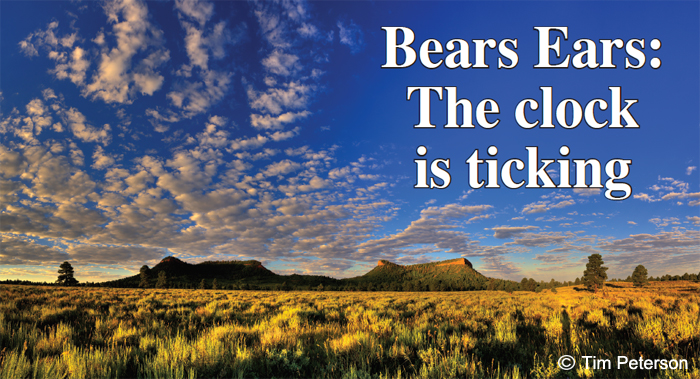

cultural site in the Bears Ears area, above Cedar Mesa and Comb Ridge. Photo copyright Tim Peterson

Critics hope any national-monument designation can be undone under the Trump administration — but it won’t be easy

Time is running down on the Obama administration, and in the Four Corners area, a lot of people are holding their breath.

Less than two months remains for the President to proclaim any new national monuments he might want to add to the list of more than 25 he has created already. Two much-discussed possibilities are the 1.7-million-acre Greater Grand Canyon Heritage National Monument adjoining Grand Canyon National Park; and Bears Ears National Monument, some 1.9 million acres in southeast Utah.

But there is opposition to both proposals, particularly Bears Ears, and now that a Republican is scheduled to take over the highest office in the land, opponents wonder whether Donald Trump and/or the Republican Congress can simply undo whatever Obama might do in the area.

The answer is “maybe,” but it won’t be simple.

‘A special category’

Unilateral actions taken by United States presidents can, in general, be rescinded or countermanded by subsequent presidents. But the century-old Antiquities Act, which gives them the authority to create national monuments, may be one exception to that rule.

“Presidents certainly have modified or revoked executive orders, and at times executive orders and proclamations have been used interchangeably to carry out land actions,” states a 2000 report by the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service on the topic of presidential authority to modify or eliminate national monuments.

“But some see the proclaiming of a national monument as a special category of action that may not simply be undone.” Another Congressional Research Service report done in 2016 found essentially the same thing. “The Antiquities Act does not expressly authorize a president to abolish a national monument established by an earlier presidential proclamation, and no president has done so,” it said.

In rare cases, presidents have tweaked the boundaries or allowed a monument designation to be “upgraded” to a national park or wilderness area.

However, Congress can and very well might endeavor to “de-designate” certain national monuments created by President Obama, particularly any created at the very end of his term.

Tim Peterson, Utah wildlands program director with the nonprofit Grand Canyon Trust, told the Free Press he believes there is still a good chance that Obama will proclaim the Bears Ears and/or the Greater Grand Canyon national monuments before he leaves office. Peterson also believes opponents will then endeavor to undo either or both of those designations.

“I would expect that Congressman Bishop would make an attempt at that,” said Peterson, referring to Utah Congressman Rob Bishop, a Republican who is chair of the House Committee on Natural Resources. “I think that’s realistic, given his statements on the record and his opposition to Bears Ears in particular and the Antiquities Act in general.”

In an effort to thwart the Bears Ears designation and possibly others, Bishop three years ago launched a massive effort called the Public Lands Initiative. After gathering input from thousands of stakeholders in seven eastern Utah counties, Bishop and other legislators including Utah Congressman Jason Chaffetz sponsored a bill offering a huge package of management measures for some 18 million acres of federal public lands in those seven counties.

One component of the PLI bill would protect 1.2 million acres of the Bears Ears area as a national conservation area, a less-restrictive designation than a monument.

However, while the PLI bill had one committee hearing in the House, it has not advanced and as of press time did not have a Senate sponsor, so it will likely have to be reintroduced in the next Congress if it is to move forward. A companion piece that sought to end the use of the Antiquities Act in the seven Utah counties affected by the PLI legislation never even received a hearing.

‘Difficult politically’

But critics say the PLI bill is not protective enough of areas such as Bears Ears, which is rich in cultural and archaeological sites. Five regional Indian tribes – the Navajo, Hopi, Ute Mountain Ute, Uintah Ute, and Pueblo of Zuni – are calling on Obama to proclaim it a monument instead, one that would be managed largely by those tribes, along with three federal lands agencies. A total of 26 tribes have individually expressed support for the monument, and the National Congress of American Indians, representing more than 250 tribes, has passed a resolution in support of Bears Ears.

If Obama does designate Bears Ears a monument, Peterson expects any effort to rescind that designation would face a battle in Congress, despite the fact that Republicans hold small majorities in both houses.

“Their success in undoing Bears Ears is a little less likely because this initiative carries such backing,” Peterson said. “That makes it more difficult politically,” he added. “It makes it different from some other monuments in some ways because there is stronger support.”

However, resistance to the Bears Ears monument proposal has also been fierce, especially in San Juan County, Utah, among both the non-Native American community and some local tribal members. The three-member county commission, including Rebecca Benally, a Navajo, is united in opposing the proposal. A coalition called Save the Bears Ears has sprung up to fight the monument.

Cultural site in the Bears Ears area, above Cedar Mesa and Comb Ridge. Photo copyright Tim Peterson

Hot issue

Federal lands in general, and national monuments in particular, have become a hot-button issue in recent years. The GOP platform approved at the party’s national convention this summer, specifically calls for the creation of no new monuments without the approval of Congress and state legislatures.

Bishop’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

A spokesperson for Colorado Third District Congressman Scott Tipton, a Republican from Cortez, said in an email to the Free Press that Tipton supports national monuments, but only if they have broad local backing. If he doesn’t believe certain ones do, he would help strive to overturn them, wrote Liz Payne, communications director in Tipton’s Washington, D.C., office.

“Congressman Tipton firmly believes that national monument and national park designations should be driven at the local level,” Payne wrote.

She discussed two areas in Southwest Colorado that were the focus of recent efforts for protection, Chimney Rock near Pagosa Springs and Hermosa Creek near Durango.

“In the cases of both Chimney Rock and Hermosa Creek, there was broad local support for designating the areas – Chimney Rock as a national monument and Hermosa Creek as protected public lands/wilderness – and Congressman Tipton worked bipartisanly to advance legislation through both chambers of Congress,” Payne said.

“In the case of Chimney Rock, the political climate was such that the Senate was not able to advance the bill, and therefore, the final option for designating the land was through the Antiquities Act.” Obama made Chimney Rock a national monument in 2012.

Payne said Tipton will rely on Utah legislators’ opinions to guide his response to any Bears Ears monument.

“Chairman Rob Bishop and the Utah Congressional delegation undoubtedly have ears on the ground to gauge the pulse of the communities surrounding the Bear’s Ears area. Should the Administration take actions that are contrary to the desires of the local communities, Congressman Tipton will support efforts taken by the Utah delegation to rectify the situation.”

Payne also wrote that Tipton would oppose any possible monument designation on the lower Dolores River in Colorado. Though the river corridor is not considered likely for a monument proclamation at this time, the idea has been broached in conservation circles. A local committee involving four counties and other stakeholders has been meeting for years to craft possible legislation to create a national conservation area instead, but Montezuma County recently withdrew from that effort.

“Congressman Tipton will oppose any unilateral designation of the Dolores River area,” Payne wrote. “The community stakeholder groups are working through the process, which should be allowed to continue without a heavy-handed unilateral designation that ignores local input.”

‘No authority’

Republican and Democratic presidents alike have used their authority under the Antiquities Act to set aside special areas. Nearly every president since the act’s passage in 1906 has employed it at least once, beginning with Theodore Roosevelt and including Herbert Hoover (who set aside what is now Arches National Monument in Utah), and George W. Bush (who created the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument).

But though presidentially proclaimed national monuments (Congress can also create them) are sometimes unpopular in the immediately surrounding communities, they enjoy broad support from conservation groups and often prove to be a boon to local tourism economies in the long run.

Still, the Antiquities Act was created to preserve, well, antiquities, and critics have fumed at the way presidents such as Bill Clinton and Barack Obama have wielded it to protect broad swaths of land, such as Clinton’s 1.9-millionacre Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in southern Utah, and Obama’s Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument, 4,913 square miles of ocean southeast of Cape Cod.

Many states’-rights advocates and others would like Donald Trump to try rescinding some or all of Obama’s monument proclamations, which cover 553 million acres of land and ocean so far, especially any that he might do in the waning weeks of his administration.

However, it’s not at all clear that Trump would prevail in the legal challenges that would inevitably ensue.

The Antiquities Act contains no language providing a means for a president to revoke another president’s monuments. There are no court cases establishing a precedent.

Back in 1938, U.S. Attorney General Homer Cummings concluded that while a president could legitimately modify a monument (something many of them have done), he could not eliminate a monument that had been created by a previous president.

“The Opinion [by Cummings] noted that there was no separate statutory authority for the President to revoke or terminate a monument, and therefore any authority that existed for this purpose must be implied by the other powers given the President in the Antiquities Act,” states the 2000 research paper by CRS.

“The Opinion then reasoned that because the President had no inherent authority over lands, the President was acting only with authority delegated to him by Congress; a monument reservation was therefore equivalent to an act of Congress itself; and the President was without power to revoke or rescind a monument reservation.”

Many presidents may be hesitant to test the legal waters regarding revoking monuments because, if it proved possible to do so, then any monuments they created could also be swiftly overturned. However, it’s certainly within the realm of possibility that Trump might not have the desire to protect any lands at all through a monument proclamation, so he might not worry about setting a precedent.

Legal analysts believe the easier way to “undo” some or all of Obama’s monuments would be to turn to Congress, which does have clear authority to abolish national monuments.

Or instead of formally “unwriting” some of Obama’s protective proclamations, Congress could simply decide not to adequately fund the special areas.

Another option is weakening the Antiquities Act itself.

“This is an issue that Congressman Tipton has been working on as a leader in the Congressional Western Caucus,” his aide, Payne, said in an email to the Free Press. “With Republican control of the House, Senate, and the White House, there may be an opportunity to pass legislation that ensures the Antiquities Act is used for its original intended purpose in the future, rather than as a mechanism to block large areas of land from multiple use.”

But, she added, “We won’t know for sure what the political climate surrounding this issue will be until we are in the 115th Congress.”

‘An attack on all’

The Grand Canyon Trust’s Peterson told the Free Press he is definitely concerned about such possibilities.

“I would expect there would be a movement among the majority in the House to limit the power of the Antiquities Act or to repeal specific monuments, but it’s just speculation,” he said.

“I am concerned about the erosion of the Antiquities Act as well as various energy policies and regulations issued under President Obama being rolled back or modified in a way that’s detriment a l to conservation.”

However, Peterson said, any such attempts will face considerable resistance.

“Polling demonstrates that Americans are broadly supportive of public lands, broadly supportive of national monuments, and should the Congress attempt to take action on [legislation to weaken those] there would certainly be a difficult fight.

“I think there’s a lot of support for the Antiquities Act in the coming Congress and it’s really hard to say at this point what might happen. We would certainly do all we can to work with allies to make sure that legislation like that did not pass the House and Senate and become law. It’s certainly something we’re thinking about moving into this new climate.”

Asked whether it might be easier for Congress to focus on undoing specific national monuments, in particular Bears Ears, should it be proclaimed as such, Peterson said he did not necessarily think so.

“There is a strong coalition of groups that will be really dedicated to defending all national monuments,” he said. “An attack on one will be viewed as an attack on all, and I’m confident recreationists, sportsmen, conservationists and many others would step forward in that case.”