In 1912, Russian painter Vasily Kandinsky published his classic statement, “Concerning the Spiritual in Art.” He spoke about the content and process simultaneously, saying, “the harmony of color and form must be based solely upon the principle of proper contact with the human soul.”

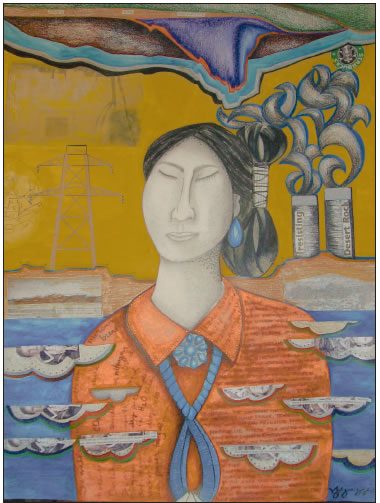

The acrylic on canvas by Venaya Yazzle, ‘Yeego’ Sodizin (Pray Hard), depicts a traditional woman in a pollution-fouled landscape. Yazzle believes Native American artists help bridge the gap between past and modern culture on Indian reservations.

Ninety-six years after his aesthetic declaration launched the abstract movements in contemporary Western art, Venaya Yazzie (Diné/Hopi), a painter, writer and political activist living in Farmington, N.M., states that Kandinsky is the most influential artist in her aesthetic development — a Eurocentric point of reference.

“Even before I read and learned about him, I experienced many epiphanies while looking at his work,” Yazzie said. “When I first saw his paintings I felt a real connection with him. I felt the content of the spiritual.”

Yazzie believes that Native American artists are spiritual intercessors positioned between what happened in the past and the reality of what is happening to Native American culture today. “We bridge the gap,” she says.

“When I close my eyes I see my job as an artist positioned in the middle of the schism, born with a talent and understanding that can help my grandparents, my mom, dad and relatives heal from what happened to them as children by painting what I see today.”

Her subject matter is firmly grounded in present acculturation issues affecting the well-being of her Navajo people. She is not ambiguous about the status and condition of contemporary Diné culture and responds by painting the images that reveal the chaos.

“If I can do one thing that I believe will benefit my people, it is using my art and writing to feed them the reality of the addictions plaguing our culture today.”

Her current visual art focuses attention on environmental issues and potential cultural genocide. She shows the viewer the constant bombardment of “bling-bling” economics, pop-culture addictions and how they erode the spiritual nature of traditional Navajo good ways of living.

“I do not depict hogans or the pan- Indian stereotypical tipi or bow-andarrow icons,” Yazzie said. “Instead, I paint the concrete life I live — the trash and dry cottonwood leaves and plastic Wal-Mart bags littering the streets of a border town in the northern New Mexico territory.”

The Navajo timeline for contact with whites lags behind the East Coast tribes who have had more than a hundred years to work through the issues. According to Yazzie’s great-grandmother, the Diné culture remained intact until they met the first white people.

The pressures from contact are still fresh, unfamiliar and seductive. “Even today we do not know what to do with the impact and remain very vulnerable to acculturation because of the newness,” Yazzie said.

In her painting, “Yeego’ Sodizin (Pray Hard),” a traditional Navajo woman stands in the foreground of a landscape fouled with pollution spewing from a coal-fired power plant. The composition requires that we turn our point of view by forcing us to look at cumulus rain clouds painted upside down, disconnected from the Shiprock reversed on the horizon.

“The clouds represent the male counterpart to the spiritual relationship between Mother Earth and Father Sky. You can see that they are no longer in contact. They do not have a marriage and are out of balance with each other.”

The content is disturbing, yet the woman is serene. “I think the only real sovereign thing we Navajo people have is our prayer,” Yazzie said. “It is the center of life. No one can take our prayers away from us.

“Our spirituality is present in her closed eyes and peaceful expression. Her prayers ask for good things, good decisions for our people and our land. She is part of our spiritual dialogue. This is the reality and the balance I want to convey in my paintings.”

Her poetry corresponds to the socialpolitical positions in her paintings. In “Benedicto for the Elders at Dooda’ Desert Rock,” she writes, “She walks in pollution / Mercury breath trails her CO2 aura / Our lady shrouded in green / ochre nitrogen oxide / sits—her desert senses swirl / and he, Sky Father watches / She sits on crackled earth / and scrapes white-dry, packed / dirt into her red mouth.”

She recently designed and curated the exhibit, “Connections: Earth+Artist = A Tribute to Resistance at Desert Rock,” on display currently at the Center for Southwest Studies at Ft. Lewis College, Durango.

“When I met Desert Rock opposition activist Elouise Brown at the 1,500- megawatt power plant site proposed by Sithe Global Power near Burnham, N.M, I remembered Kandinsky writing that art is spiritual in what is does for the artist, a way of healing the inner self.

“To be an artist you are always thinking about yourself first. Once your images help yourself then they begin to go out and help others.”

Native artists are working through their own healing and self-identity issues around Nativeness, she says. “Whether it is on a visceral or spiritual plane we eventually become the conduit for addressing the cultural terror associated with the direct atrocities visited upon our families in the past as well as those we see acculturating through the rose-colored glasses we are choosing to wear — the narrative I work with today.”

Many elders do not have a voice because their education has been limited. “No one will listen to them,” she says, “because they do not know how to represent themselves in Eurocentric language.”

In the early 1990s Yazzie attended the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, N.M., where she began painting images about self-identity. “I had to go through the process myself to understand who I am as a human being. It was an empowering stage because I learned that I could grow into a voice for others by using knowledge incorporated from an academic base and combining it with my inherited tribal wisdom.”

Venaya is completing her master’s degree in education at the University of New Mexico. She has participated in 36 exhibits since 1996. She is a prolific professional artist and graceful in her conduct as speaker and advocate.

“People ask me why I am not a weird, far-out, pop-culture artist making big bucks in the art markets. . . but, I choose to express political content because my great-grandmother received her U.S. citizenship in 1924 when she was 17. My lesson from her is that since then I can be free about my voice. Unlike her, I was born into citizenship. I am not an alien.”

Today Yazzie chooses to paint and write about social ills such as racism in the border towns around the reservations, while also informing her own people about the addictions eroding the Navajo culture today:

“Grey smoke stack streams and / twilight change her moods / under her eyes prayer words / float and swirl all around her / Her 21st century circular rituals / surge in the palm of her hands / like star explosion / she carries earth mountain sacraments / in her shiny silver belt.”

Yazzie is born to the Manyhogans clan, born to the Bitterwater clan, the Waters Flow Together clan and the Hopi Nation. As a child she grew up seasonally on and off the eastern Navajo reservation at Huerfano, N.M., in the shadow of Dzi_ná’oodi_ii. (Huerfano Peak).