A March 19 decision by the Bluff Service Area Board to take no action regarding its sewage-treatment options has left the town in limbo and at least one board member aghast.

The meeting was purportedly held so the board could decide which of two fundable options for sewage treatment it should present to the Utah Division of Water Quality. Instead, the board voted 4-3 to take no action, prompting its chair to resign in frustration.

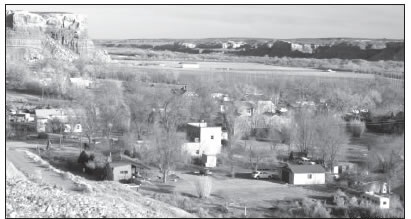

A decades-long controversy over wastewater management in scenic Bluff, Utah, has heated up once again with the recent decision by the town’s Service Area Board to take no action on a centralized sewage-treatment system. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

“It’s a horrible situation,” said former chair Dr. Dudley Beck, a physician with Indian Health Services for 38 years, who resigned the day after the vote.

He said he had been on the board about five years, “and I feel like I’ve totally wasted five years of my life for a community that doesn’t deserve the board’s efforts.”

“I’m so sad and so disappointed,” Beck said. “It’s been an emotional nightmare.”

The Service Area Board looks after issues such as garbage, recreation and mosquito abatement for the unincorporated town of about 320 on the northern bank of the San Juan River. For several decades, one of the community’s biggest issues has been sewage treatment.

The state and the county have pushed Bluff to install a centralized wastewater system instead of relying on individual on-site septics, but many locals have resisted, maintaining that the cost would be high and that there is no need in such a small town. But advocates insist a system is necessary because of Bluff’s proximity to the river and the fact that its soils are not ideal for handling septic-system effluvia.

In May 2008 the Service Area Board voted to pursue funding for a decentralized sma l l – p i p e collection system and applied for grant money to complete the design phase.

The recent meeting was intended to see which of two treatment options the community wanted to pursue, according to Skip Meier, now the board’s chair.

“The whole purpose of the meeting. . . was to see which of the fundable options we were going to submit to DWQ to seek funding,” said Meier. Only two options were fundable, he said – a small-pipe collection system with treatment and surface discharge; and a largepipe system with a lagoon. Each would have cost abut $5 million.

“This is where it gets sort of fuzzy,” he said. “The board was to vote on which option we would present to DWQ, but somehow two options which were not fundable, and which were not really the purpose, were included, and then four trustees voted to do nothing.”

Meier said he had favored the small-pipe system, which was the least-expensive treatment alternative and the one favored by Nolte Associates Inc., the engineering firm hired to study the situation and propose options.

Beck, who also voted for the small-pipe system, charged that opponents of any centralized system sabotaged the entire effort.

“This community was requested five years ago to tell us what they wanted, and they all told us, and we went down a path to make that happen, and in the final hour they come in the back door and stab us in the back,” he said. “They get some of their cronies on the board at the last minute and vote to shut down any effort to solve a problem that’s been plaguing the community for 30 years.”

At present, Meier is the only board member that has run for office in a contested election. The remaining trustees were appointed to fill vacancies; some would have run in the most recent election but had no opposition.

“Nobody wants to be on the board – it’s a miserable job. In the past nine months we’ve had people quitting, and then people who want to stop this whole project volunteer to be on the board. They come in late, they refuse to work – their sole purpose was to block this,” Beck charged.

About three weeks prior to the meeting, the board sent an electronic poll to a group e-mail list so town residents could comment on the treatment options prior to the final vote, Beck said. The poll was not an official vote and was open to anyone who wanted to respond, including homeowners, renters, even visitors.

The board secretary removed signatures on the e-mailed responses before giving them to the trustees. By 11 on the morning of the meeting, Beck said, the tallies were roughly equal, with 20-some respondents favoring doing nothing and the same number each favoring a small-pipe system or a large-pipe lagoon system.

In the next few hours, however, the number favoring no action zoomed up to around 60 while only a trickle of responses came in for the other categories, Beck said.

“It just makes you wonder,” he said.

In the end, 59 – a plurality – preferred no action, and 65 votes were split among the different treatment options.

“Fifty-nine wanted to do absolutely nothing,” Meier said, “whereas 65 wanted to do something. So the majority who responded to the poll wanted to do something, but the trustees said the majority wanted to do nothing, so that’s where everybody’s upset.”

But Jackie Warren, a recent board appointee who opted for no action, said the furor over the vote was something of a non-issue, considering that the state reportedly has no funding available for any type of treatment.

“At the end of the meeting on Saturday with the state and geologists, etc., they said there is not enough money to fund this option, any option. That is how they ended the meeting. So the vote is kind of ludicrous,” Warren said.

“It’s kind of a no-brainer. There isn’t any money, the whole town doesn’t want it, and we don’t need it.

“I don’t know why they were making everybody jump through the hoops when they didn’t have the money, but they said, ‘You need to go through these procedures so when money becomes available, you know what the people want’.”

Warren contends there is no problem with residential waste disposal in Bluff. “Absolutely not,” she said. “All the new septic tanks and leach fields have been approved.”

She said she’s done her homework and cited a report by David Snyder, an engineer with DWQ, that found no widespread problems. “There are a few small lots that are very old that shouldn’t even be built on, and that’s a zoning issue that the county controls. If the county approves your building permit, who’s at fault if your lot is too narrow for even a house, let alone a wastewater system?

“That’s what we’re going to work on. When people voted ‘do nothing’, it wasn’t do nothing, it was, ‘do not accept any of these options because two of them they wouldn’t fund anyway, so let’s figure out what to do with the narrow lots,” she said.

“At the meeting, DWQ said we had pristine groundwater in Bluff. ‘Pristine’ was the word they used.”

Meier, a longtime board member, believes that assessment is too rosy. He said there have been a number of septic failures on residential properties and several notable failures of larger systems.

A July 2005 report by Nolte found that in Bluff, “Many onsite systems already failed or are malfunctioning while many systems have potential to fail or malfunction in the future.” The report said the failure rate of 10 percent or more in two years among the 122 systems was disturbingly high.

“When the school’s system failed nine years ago, there was raw sewage on the playground, and when the Twin Rocks [Café] leach field failed, the septic tanks were pouring raw sewage into Jackie Warren’s yard,” Meier said. “And of course Recapture Lodge – it was the same sort of thing.”

In September 2009, Recapture, one of Bluff’s largest and most prestigious businesses, was issued a notice of violation by the Utah Division of Water Quality for failures of its waste-disposal systems and the unauthorized discharge of wastewater and sludge into an unapproved lagoon system.

A bilateral compliance agreement has since been worked out between the lodge and the state, and the lodge recently reopened its laundromat, which it had voluntarily closed when the notice of violation was issued.

Warren, who works at Recapture, said the failure there was an isolated incident caused by freak circumstances.

“The day the state came down was the day we had had 70-mph winds and the power was out for six to eight hours. We had electric lines lying on the highway and the whole fire department and everybody was running around town,” she said.

Recapture has its own sewage plant, but that shut down for six hours, which was when the state did its testing, Warren said. Recapture has since installed a new battery backup system.

Meier said there remain serious concerns about the individual septic systems in Bluff. Many were not built to existing standards, he said, and the state health department has the authority to require lots with non-compliant systems to become compliant when the systems fail. The problem is that some of the lots are too small to support an on-site system.

“They are probably going to have to do whatever is necessary to meet standards, whatever that means, and whatever that means is where the big question is,” Meier said.

“Can the place be red-tagged? Can occupancy be vacated? Are they going to allow alternative systems? Are they going to allow the effluent to be treated and taken off-site? All of these very vague things which have been totally avoided for the past 50 years in the state of Utah are going to be coming to a focus in Bluff.”

Beck concurred. “They [central-system opponents] have chosen to call the bluff of the county health department, the county commissioners, the state, and I would be extremely surprised if the current wastewater rules and regulations are not implemented in a way that will cause harm to many poor people in this community.

“People have invested their life savings in small places and now they risk losing them, and there’s people that don’t care. That’s what angers me the most. It makes me ashamed.”

He said some of the blame belongs to San Juan County. “I think it’s sad the county has let things get to this point. They’re way too lenient on rules and regulations. They control the building permits and for 40 years all they have cared about is growth.

“People have been sneaking around for years – what do you do when your system fails? You get some local to come in in the middle of the night and dig a ditch so people won’t know there is a failure.”

A pressing concern posed by the situation is the upper aquifer beneath Bluff, according to Meier. When a system fails, a typical response is to dig deeper. “If you put it deep enough, it won’t surface, now will it? So then it goes into the aquifer.”

Inspection reports on septic systems are generally vague and incomplete, he said. “We might know that a leach field was put in at the bottom of a trench at 10 feet down, but we have no idea if it was ever checked to see if the water table ever reached 10 feet.

“The untreated effluent is being put deep so it won’t surface, but that allows it to get into the ground, so that’s your potential risk. You’re not preventing it from reaching the groundwater.”

Meier said test wells have indicated that the upper aquifer is being influenced by humans, though not necessarily contaminated. “Things like chloride and sulfates and ferrates that couldn’t have gotten there any other way were present,” he said.

He said the three aquifers below Bluff are all interconnected and are also connected to the San Juan River, and if contamination ever reaches the river, the federal government will step in. “They don’t sit around and hem and haw. They say, ‘You shall cease and I don’t care how’.”

Warren thinks such concerns are exaggerated. “You know what? We could get a tsunami here, too.”

She said groundwater test wells have found no contamination.

“Groundwater moves very, very slowly. They’re saying 10 to 20 years before they would even bother to retest them because that’s how long it takes bacteria to move through groundwater.

“We can worry about a lot of things, but they have the test wells in place, they will check them, and for the last 120 years the people have lived in this valley. It’s not contaminated.”

She mentioned a remark by David Cunningham of the Southeastern Utah Health District that septic systems are at inherent risk of failure. “Let me tell you, so is my body,” Warren said. “Should I go to a nursing home now at 62? Should I just sign myself in because I’m going to die some day? Or do I take care of myself?

“I’m inherent to failure but I’m taking care of myself and that’s how leach fields or septic systems work. It’s God’s plan. Bacteria goes into the ground and breaks down.”

Beck believes implementing a central treatment system would be the best way for Bluff to take care of itself. He said there is a genuine health risk in the current situation, and that risk needs to be tackled. “It could be dealt with through a central system that is preventive in concept, and to not do that is taking an incredible risk in a droughtstricken area where water is so critical.

“I think people are crazy to take that risk.”

Meier agreed. “A lot of people are aware of what happens if you don’t keep your waste under some sort of control and observation – it’s a dangerous thing. Not quite as dangerous as released radioactivity, but released poop can be dangerous.”

Marilyn Boynton contributed background information to this report.