Goodnight’s sculptures celebrate animals and the American West

“Look at your hand and turn it 360 degrees. You can see how much form there is in that,” Mancos artist Veryl Goodnight replies when asked why she uses live models to create her bronzes and paintings.

“Photography is very limiting. It can distort. It keeps me excited to have my subject in front of me in motion.” Her subjects are usually animals. They rule her life. She met her husband, Roger Brooks, on horseback, and describes herself as “dog-crazy.” “Loving animals has been the driving force in my work coming on 40 years now.”

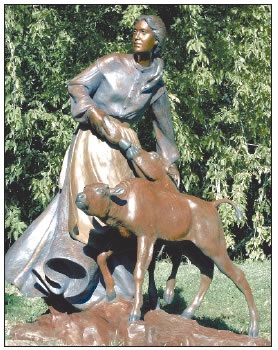

This sculpture by Veryl Goodnight, called “Back from the Brink,” depicts pioneer Mary Ann Goodnight feeding a bison calf. Goodnight owns the Goodnight Trail Gallery in Mancos.

So has family history. She often recreates the animals in the lives of her distant cousin, cattle baron Charles Goodnight, and his wife, Mary Ann. His story piqued Veryl’s interest when her father had her name her dachshund “Gretchen Goodnight.”

Later, J. Evetts Haley Jr., son of Goodnight’s biographer, approached her to create a lifesized sculpture of one of Goodnight’s cows, Old Maude, for the Haley Memorial Library and Research Center in Midland, Texas.

That and a trip on the Goodnight Loving Trail with a chuck wagon and longhorns hooked her. She became especially intrigued with the story of how in the 1870s, at the height of the bison slaughter on the Great Plains, Mary Ann begged Charles to bring her the orphaned calves to bottle-feed. Ultimately, the Goodnights helped restore the bison to the prairies.

Veryl Goodnight decided to sculpt Mary Ann feeding a baby bison, but needed a little one to observe. “I put out inquires to people who knew me and wouldn’t think I was crazy when I asked if they had an orphan buffalo I could raise.”

A friend offered her a calf named Charlie. Goodnight thought he came on loan, but the buffalo bonded to Roger Brooks, often barging into the house to find him.

“I replaced [the lower part of the screen door] a couple of times and he kept poking his head through,” she laughs. “I finally taped a little piece of paper across the top that said ‘buffalo door’.”

Charlie’s owner gave him to Roger. Even after Charlie grew to 2,000 pounds, “He was still as gentle as a dog,” says Goodnight. “It’s one of the most beautiful connections between animal and human being I’ve ever seen.”

The sculpture, “Back from the Brink,” depicts Mary Ann Goodnight holding a bottle for a calf.

Veryl Goodnight started her art career drawing on her math, English, and history papers in school. Arriving in college in 1965, she painted wildlife and horses instead of the abstract forms popular at the time.

“They were putting paint on bicycle tires and riding over canvas,” she recalls. Disenchanted, she turned to sculpture to teach herself anatomy; and to understand movement and plane in an image.

Today she both paints and sculpts. To compose a statue, she begins with video to establish the best position for the animal. “I can print off the most exciting pose.”

Still photography and sketches give her a sense of her model’s form. When she’s ready to work, she sets a revolving stand in front of her subject, rotating it as the animal moves and working on the part the animal presents. Sometimes models stick their noses in the middle of her work. “I’ve lost a lot of ears, heads, legs to their participation,” she laughs. “But a lot of animals have creative juices running in them, too. They want to help.”

Currently, a Santa Rita longhorn named Gordie is lending a hoof with a sculpture of Old Blue, the steer Charles Goodnight used to lead cattle along the Goodnight Loving Trail from West Central Texas through New Mexico and Colorado to Wyoming. When Veryl Goodnight finishes the clay moquette, her founder of 25 years, Dmitry Spirdon, will cast it.

When not sculpting Charles Goodnight’s story, she enjoys modeling strong pioneer women and particularly likes her piece “A New Beginning,” depicting a lady in a traveling costume of 1890, the year Wyoming women got the vote. The lady looks ready for heady adventure.

Goodnight considers “The Day the Wall Came Down” her best-known sculpture. Depicting five horses jumping over a crumbling Berlin Wall, it stands in Berlin in front of the Allied Museum. A second casting stands at the George Bush Presidential Library at Texas A&M University.

When commissioned by Bluebell Creamery of Brenham, Texas, to create its logo, Goodnight asked her young neighbor, Chessie Kimble, to pose leading a cow. Out came the life-size bronze, “Country Living.”

In Mancos, Goodnight shows her work at the Goodnight Trail Gallery of Western Art, which belongs to her husband. The gallery also carries work by painters Rose Sandifer, Carole Cooke, Ralph Oberg, and Wayne Wolfe. Sandifer also sculpts.

Photographer Barbara van Cleve has published many books, including “Hard Twist,” on Montana ranchwomen. Sculptor Patsy Davis worked for Disney and Warner Brothers before retiring to specialize in life-size dogs. Bill Nebeker sculpts horses and other wildlife. Mike Desatnik works with native American subjects. Bonnie Bryant creates painted jewelry.

The gallery also carries vintage Navajo rugs, Western books, and saddles by Lisa and Loren Skyhorse. Many of the artists have known Veryl Goodnight for most of her professional life. Most have national reputations.

“We love {the gallery},” says Goodnight. “The term ‘Western’ is broad. It can be a landscape, animals, a seascape, as long as it depicts the culture of the American West.”