Colorado is headed for warmer and drier days and less water, according to two new studies. And that’s likely going to require some fancy accounting when it comes to water supplies in the Colorado River basin.

The first study was led by Greg Pederson, an ecologist with the USGS in Bozeman, Mont., and was released last month in the journal Science. Pederson and his colleagues used tree-ring records to determine that the past 20 years have seen record lows in snowpack across the North and declines throughout the West, even though – compared to that trend – this past year was abnormally robust.

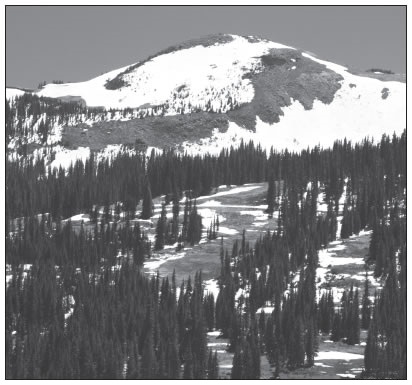

Snow still sits on the San Juan Mountains in late June, but a recent study of tree-ring records found that snowpack is shrinking in the northern Rockies. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

And the study authors say warming temperatures throughout the Rocky Mountain and Greater Yellowstone areas may be overriding natural variation as the primary driving force behind the winter storms that dictate the snowpack each year.

The second study is called the Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study. Its authors hail from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and the seven Colorado River states, and they’re attempting to use all available information – including climate records, computer models and water-use data – to predict future supply and demand for Colorado River water.

So far, the findings are general and not too encouraging: The Colorado River is projected to contain about 9 percent less water over the next 50 years, with droughts lasting 5 or more years occurring about 40 percent of the time.

| For more information on the ongoing Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study see www.usbr.gov/lc/region/programs/crbstudy |

“It is a good indicator that there could be shortages in the future that we all need to be planning for,” said Bruce Whitehead, executive director of the Southwestern Water Conservation District in Durango. His district, authorized by the state legislature in 1941, manages water supplies for nine counties in Southwest Colorado including Dolores, Montezuma, La Plata and San Juan.

Throughout Southwest Colorado, maintaining water supplies for cities and farms is going to require careful management of the reservoirs, efficiency, conservation – and some wheeling and dealing where water rights are the currency.

Good year

Despite a general trend of warming and drying, most of Colorado has enjoyed a great spring. To start with, the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) documented record levels of snowpack throughout the Colorado River’s northern headwaters.

“Even many of the old-timers have never seen some of the depths measured across northern Colorado this month,” Allen Green, state conservationist with the NRCS, said in a May statement about the records.

That could have spelled disaster, if higher-than-normal temperatures through May and June had sent snowmelt gushing to overflow the rivers. Unlike other parts of the country, much of Colorado also got lucky in that respect.

“It’s really been ideal, especially up north, which has helped to reduce flooding issues,” said Mike Gillespie, a snow-survey supervisor with the NRCS in Denver. “Our snow melt has progressed in an orderly fashion with only minor problems reported from high-water issues across northern Colorado.”

In the southern half of the state, weather has proven less ideal. Extreme drought in southeastern Colorado has sent water levels in the Rio Grande and Arkansas reservoirs plummeting to 24 percent of capacity.

Statewide, Colorado’s reservoirs are at 57 percent of capacity, or 92 percent of average – but mostly that’s a reflection of the southern basins pulling down otherwise strong levels.

The San Miguel, Dolores, Animas and San Juan river basins, measured together, are at 110 percent of average volume, and at 91 percent of capacity. That’s not because the snowpack in Southwest Colorado was especially strong. It wasn’t. But reservoir operators kept a tight rein on water releases.

“This year has been one of remarkable contrasts,” Gillespie observed, “with record- high snowpacks across northern Colorado to extreme drought conditions in the southeastern corner of the state. Colorado once again finds itself sitting on the fence between contrasting climatic conditions across the western U.S.”

Waning snowpack

If the Science study findings are predictive, springs like this one could become increasingly rare in northern Colorado. In general, Pederson and his colleagues found, warmer springs are reducing snowpacks in the Greater Yellowstone and the Rocky Mountain regions, so there’s less snowmelt feeding their respective watersheds – the Columbia, Missouri and Upper Colorado rivers.

The tree-ring records revealed that the snowpack reductions across the northern Rockies are almost unprecedented over the past thousand years.

According to Pederson, since the 1950s, snowpack has declined by 30 percent across the West, with the lowest elevations and costal ranges exhibiting the greatest declines (up to 60 percent). The highest and coolest elevations have not registered as severe a decline, and in some cases individual records show level to modest increases in snowpack. “This too is expected, and reflects the important role temperature plays in controlling snow accumulation,” Pederson said.

He said a 2008 science paper by Tim Barnett (Scripps) and others estimated that 30 to 60 percent of those declines were caused by human-induced, or greenhouse gas, warming.

But what’s more stunning is the shifting climate patterns that are driving the decreases. Historically, it appears that natural variability dictated a sort of tug-of-war between the Greater Yellowstone and Northern Rocky Mountain regions feeding the Missouri and Columbia rivers, and the southern Rocky Mountain region feeding the Colorado.

That story starts with changing sea-surface temperatures that drive the El Niño and Pacific Decadal oscillations, which in turn trigger north-south shifts in storm patterns that dump precipitation over one region or the other.

But there are periods of time in the historic record – for example in the 1350s and the 1400s – when regional air temperature reduced snowpack over both places at once. And it looks like that’s happening again.

Until the 1980s, the higher and cooler elevations of the southern Rockies region seem to have buffered the snowpack from substantial temperature-driven losses, the authors say. But warming is pushing mean winter temperatures above the freezing point at important snow-accumulation areas across the Rockies, at times when snowpack would otherwise be growing. And that means less snowpack to fuel spring snowmelt into the Colorado River’s headwaters.

Higher temperatures can also mean less late-summer runoff because the warmer temperatures melt the snow earlier, trigger precipitation that falls as rain rather than snow, and increase evaporation.

The study “foreshadows fundamental impacts on streamflow and water supplies across the western USA,” the authors write. “When coupled with increasing demand, additional warming-induced snowpack declines would threaten many current water storage and allocation strategies.”

Hedging bets

Colorado’s water managers are aware that current storage and allocation strategies have their limits, which is why they’re active-ly looking ahead. As executive director of the SWCD, Whitehead oversees efforts to make sure this area’s storage and allocation strategies hold up even in a harsher climate.

The Bureau of Reclamation report has already shown that “in a 10-year average, use has now outstripped supply” in the Colorado River basin, said Terry Fulp, deputy regional director for the agency’s Lower Colorado region, in a webinar about the early findings.

Besides a handful of rural wells, nearly all of Southwest Colorado’s water comes from surface flows. So far, there’s one factor standing between that overall water deficit and dire shortages: reservoirs. McPhee numbers among five reservoirs in the Dolores, Animas and San Juan basins. Together, they have a capacity of 680,000 acre-feet.

But already in some drought years, cities have run a bit short. In 2002 and 2003, for example, Mancos, Cortez and Pagosa Springs implemented outside -watering restrictions. Durango requested voluntary curtailing of outside watering, but didn’t have to impose restrictions – partly because that city has landed a bulletproof waterrights portfolio.

Water rights, whether they’re owned by cities, farmers or other users, come with a seniority date. When water rights are bought and sold, their seniority dates go with them – and the oldest water rights are the most valuable because they get fulfilled first. All the cities own portfolios of water rights with mixed histories.

For example, “Durango holds some of the most senior rights on Florida River, but then their portfolio extends to more junior rights that aren’t always fulfilled on a daily basis even in a normal year,” Whitehead said.

Teasing out exactly which water rights would dry up in an increasingly hotter and drier climate would be nearly impossible, Whitehead said – no one’s attempted it yet.

That’s not only because of the tangled web of priority dates, but also because the day-to-day changes in water flow are just as complex. For example, a hotter-than-average May could melt even a poor snowpack to send ample water down the Colorado for a water user needing to exercise his water right during that month, as long as he’s not impacting senior withdrawals. But that same user might be out of luck after the spring rush dies down – or if a senior irrigator takes his full entitlement that day.

The high-stakes nature of those limits means Rege Leach’s job can get prickly during a drought. Leach is the division engineer for Division 7 of the Colorado Division of Water Resources, which covers the area between Red Mountain and Wolf Creek Pass south and west to the New Mexico and Utah state lines.

If the predictions in the studies hold true, more people will be shut off earlier in the year, he said: “It will definitely increase the intensity of our job; people will be angry about not getting water.”

He says most of the long-time water users in Southwest Colorado know to expect drought. “People have seen these fluctuations before,” he said. “In the early ’50s there was a series of droughts even more severe than in 2000, in terms of the number of years of drought in a row.”

Still, conflicts can arise when in-stream diverters accidentally – or knowingly – withdraw water that’s on its way to fulfilling a more senior water right. It’s the occasional deliberate dishonesty – born out of desperation, no doubt – that gets people so riled they call Leach’s office.

“We see those kinds of conditions on the La Plata every year,” he says. “There’s so much more demand for water than there is water, even in a good year. People are very tuned in to how much water is in the river, who’s diverting. It’s almost self-policing.”

Whitehead and his board are working on several fronts to make sure impacts from shortages stay at a minimum. Building additional storage to buffer lean years is one front – the Animas-La Plata project, filled for the first time last month, is an example. Built to satisfy Indian water rights, it also provides storage for use by non-Indian entities.

Water conservation and maintaining current infrastructure will be other key aspects of a workable solution, but not silver bullets.

In addition, the SWCD and the Colorado River Water Conservation District, which performs the same function for 15 West Slope counties, are working together on the concept of a water bank, an arrangement where irrigators could voluntarily fallow their irrigation ground and allow a more junior use – like a critical withdrawal in a city’s portfolio — to get water.

“The idea would be to have those folks who own those senior water rights to be compensated,” Whitehead said, adding that the idea is to make sure the critical uses – as in cities — don’t end up running dry.