Nuclear energy can power millions of homes without emitting significant pollution, making it an attractive alternative to burning fossil fuels. But mining the uranium to power nuclear plants can produce political division, racial injustice and environmental degradation.

Indigenous tribes still suffer from horrific health problems and lingering contamination to land and water as a result of the last uranium boom, which fueled the nuclear-arms race of the Cold War. As a result the Navajo, Havasupai and Hopi peoples have banned uranium-mining on their lands and are fighting mines proposed on their borders.

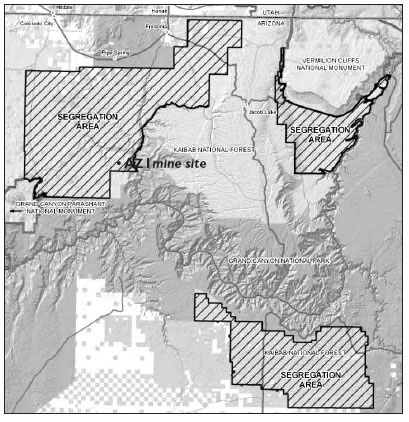

This map shows the areas near Grand Canyon National Park in Arizona that have been placed under a “segregation order” banning new uranium mines for two years. However, mines with valid existing rights can continue to operate. Photo courtesy of BLM

But elsewhere, uranium is experiencing a resurgence. Near the Grand Canyon, a mine known as Arizona 1 symbolizes the struggle between demand for the relatively clean energy of nuclear power and the desire to protect our health and natural heritage.

The mine has approval from the BLM, and is touted as a new domestic energy source and an opportunity for jobs. But it is being challenged by environmental groups who say its permit has long expired and that it should be re-evaluated based on new ecological circumstances and scientific information in the sensitive Grand Canyon watershed.

“The legacy of past uranium-mining still lingers as deadly contamination of land and water near the Grand Canyon, and to think that new mining will yield different results is foolish and irresponsible,” said Taylor McKinnon, public-lands campaign director for the Center for Biological Diversity, an activist group known for challenging industry and government in court.

“If the U.S. decides to build new nuclear plants, and intends to source that material from domestic mines on public lands, then the consequence will be adding to a high radioactive-contamination burden that already exists throughout the Four Corners area.”

The center, along with the Sierra Club, Grand Canyon Trust and the Kaibab-Paiute Indian tribe, is suing the BLM for allowing the Arizona 1 mine to re-start without conducting supplemental environmental reviews after it sat dormant for 15 years. The traditional hard-rock mine sits on BLM lands 10 miles north of Grand Canyon National Park, and 35 miles south of Fredonia, Ariz. The ore will be trucked through a portion of the Kaibab-Paiute reservation on its way to the White Mesa Mill near Blanding, Utah.

Last summer, Interior Secretary Ken Salazar issued a segregation order that bans new uranium mines for two years on nearly 1 million acres of public land surrounding Grand Canyon National Park in order to better study mining’s environmental impacts.

However, mines with “valid existing rights” issued before the July 21, 2009, order — which includes the Arizona 1 mine — are exempt from the ban, a point of contention that has spurred a legal battle for public records and calls for increased federal scrutiny of mining impacts around the park.

The temporary segregation order could expand to a 20- year moratorium on mining in the area, called a mineral withdrawal, depending on the results of an ongoing environmental impact statement on the region due out next year.

A changing landscape

The Arizona 1 mine, owned by Denison Mines of Toronto, Canada, had shut down because of a poor uranium market in 1992, but was revived in 2007 after prices rebounded and is operating today on the original permit issued in 1988.

“The segregation [order] is subject to valid existing rights, so it does not stop all mining activity,” explained Scott Florence, BLM manager for the Arizona Strip district, where thousands of uranium mining claims are located. “Arizona 1 is a previously permitted mine, so it does not stop it and neither would a longer term withdrawal.”

But environmental groups disagree, arguing in their lawsuit that the mine’s permit and plan of operation are invalid because they expired after 10 years. They say the mine’s impacts must be judged in the light of new data regarding groundwater hydrology in the area, as well as changes in the landscape such as the arrival of the endangered California condor, increased tourism and more residents.

According to the revised lawsuit filed last month, the BLM 1988 Decision Record for the mine stated that “the duration of this operation is approximately 10 years,” and that BLM regulations provide that a plan of operations “remains in effect” only so long as the claimant is “conducting operations.”

“You can’t pretend this thing is still a valid mining plan when for 15 years nothing was going on at the site, or say that nothing has changed in the area for the last 20 years,” Roger Flynn, an attorney for the environmental groups, told the Free Press. “The BLM’s own regulations say it expires.”

The BLM disagrees, noting that some changes were made to the permit, such as a larger reclamation bond that corresponds with current prices, and a requirement that the mine obtain an air-quality permit from the Arizona Department of Environment, which it did. But additional studies beyond the original 1988 environmental assessment (a less-rigorous analysis than an EIS) were not required and the permit to mine had not expired.

“The plan of operation remains in effect until for some reason the company wanted to do something that was outside the scope of the original plan; then that might trigger a revision,” Florence said. “Basically, once the plan is approved, and they continue to operate within the parameters of that plan, then they can go until the mine is mined out and reclaimed.”

As far as changes in the area, the BLM is not convinced they require additional study, not even potential impacts on the endangered California condor, introduced to the area in 1996.

Under the Endangered Species Act, federal agencies are required to consult with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to protect endangered animals near a project area. But Florence said consultation was not required in this case because the condor falls under an “experimental population” designation and therefore “doesn’t have the full protection of the ESA; it puts them outside the realm of a regular listed species.”

High-paying jobs

Are the mining claims still valid?

“We believe so,” said Ron Hochstein, president and CEO of Denison Mines, in a phone interview. “The mine still holds its full plan of operations from 1990 when the shaft was sunk, but then it was stopped because of low uranium prices. We were put on care and maintenance of the mine, and when uranium prices justified going back in, that is when we started work again.”

Hochstein downplayed the environmental impacts of the smaller mine, and said it brings good jobs to an economically suffering region.

“People wrongly think these are very large open-pit mines, but they have a very small surface disturbance, between 10 and 20 acres, and are mined out and fully reclaimed within five years,” he said. “After it is done, you would not know a mine was even there.”

The Arizona 1 mine will produce some 50 local and contract jobs, he said. The ore is being trucked 300 miles to the White Mesa Mill in Blanding, Utah, also owned by Denison. That mill, the only uranium mill operating in the country, will employ up to 130 people once it is fully ramped up.

White Mesa processes the ore into yellowcake, a concentrated form of uranium that is shipped off to be processed into a gas and then into fuel rods for nuclear power plants.

Denison Mines also plans to re-open two other uranium mines that company officials say have valid existing rights in the segregation area – the Canyon Mine and the Pine Nut Mine — and has mines already operating in Utah and Colorado.

“We are hiring at all of our mines right now,” Hochstein said. “The U.S. wants to supply its own destiny; I don’t know what’s worse, having to rely on the Arabs for oil or the Russians for uranium.”

Hochstein said environmentalists’ contention that more studies are needed “are just allegations; there is no scientific reason we should not be mining.”

Eight linear feet

The BLM has eight linear feet of information regarding mines owned by Denison Mines in the segregated area, according to an agency response to a Freedom of Information Act request by the Center for Biological Diversity.

“But so far we have only received about three inches of that,” said Mc- Kinnon, whose office is suing the BLM in a separate lawsuit for refusing to disclose the public records. In order to makes its case against the Arizona 1 mine, more information is needed on the original plan of operations and environmental reviews, he said.

“[President] Obama has given very clear directions to federal agencies to carry an assumption of disclosure, but the BLM has taken the opposite approach, and rather staunchly at that. They are behaving as a fiefdom, not as public agency.”

The BLM says there are approximately 10,600 claims being mined within the boundaries of the segregation order and proposed 20-year withdrawal. Salazar’s order grandfathers mines that have “valid existing rights,” a complicated legal distinction that is hotly debated and not clearcut.

But BLM officials say they have discretion in deciding on a valid claim. Mine owners must have done exploration and must prove the existence of a valuable mineral deposit, a fact that may or may not be verified by the BLM, before operations can begin.

“That is the Catch-22 if a withdrawal were to be put in place,” Florence said. “If the claim had prior exploration and could show they had an economically viable deposit, then most likely the claim would be found valid, but if they had not done any exploration then they probably would not be able to do that after a withdrawal.”

“The clear intent of the segregation order was to limit further activity to those mining claims,” countered McKinnon. “To my knowledge, none of the mining claims have valid existing rights because despite their own regulations, the BLM and the Forest Service never required mining companies to establish those rights, which they are supposed to do.”