I was a rookie crime reporter for the Cortez Journal 10 years ago when I got the call that a body had been found down by the sewer ponds on the southern edge of town.

At first, we assumed it must be a local homeless person, because police said the identification on the body didn’t match any pending missing-persons reports. Little did we know that this death would trigger a chain of events that would turn the town upside down.

Fred Martinez, Jr., a Navajo teen who liked to dress in women’s clothing and considered himself transgendered, was brutally murdered in Cortez on June 16, 2001.

Discovery

The body was in fact that of Fred Martinez, Jr., a Cortez 16-year-old, and he had been beaten to death the night of June 16, 2001. His body lay in the blistering summer sun for several days before two young boys stumbled across him. It took a few more days before the Montezuma County Sheriff ’s Office released his identity, but just one short interview with a handful of high-school students to paint a picture that would set the stage for a very public confrontation of homophobic fervor, cultural differences and community reflection.

The day the authorities released Fred’s name, I went directly to the high school with a yearbook in hand, on a mission to find out who Fred was.

A group of girls gathered on the steps of the school at lunch provided me with my first glimpse into Fred’s world. Without hesitation, they told me that Fred was “different” because he carried a purse, tweezed his eyebrows and wore makeup on a daily basis.

They were quick to say that he’d been made fun of at school, and was the butt of many jokes. His sexuality made him stand out, and his differences made him an easy target for bullying, or worse.

I included these few details in the next day’s article, though it was somewhat buried in the second or third paragraph. The District Attorney’s office issued only a brief statement that it wasn’t appropriate to speculate on whether Fred’s sexuality was a motive for the murder because “all crimes were hate crimes.”

However, the Associated Press picked up the story, moving his sexual orientation to the forefront and thrusting the small-town murder case into the national spotlight.

From that point on, I was no longer the only reporter on the case.

Meet the press

Reporters from across the country flew in to cover the story, and Cortez was suddenly a town under the microscope – just as it had been three years earlier, when three men stole a water truck, killed a Cortez police officer, and fled into the desert, triggering a massive manhunt.

I wasn’t at the Journal then, but people told me there was a similarly charged atmosphere in the town. Fred’s murder drew widening attention as the news spread. Lesbian, gay, transgendered and bisexual (LGTB) organizations took note, and their representatives were quick on the scene.

I wrote dozens of stories that summer on the Martinez murder, and with each article I was confronted with the challenge of how to cover the case.

A constant stream of letters to the editor in the Journal exposed a conflicted community, and forced me to do a gut check on what constituted responsible and ethical journalism. The paper in general, and I specifically, were criticized for paying too much attention to Fred’s sexuality – or too little. For every opinion there seemed to be an opposite one, and people were voicing them all.

As a reporter, I did my best to report the news fairly and accurately, carefully phrasing everything I wrote. But I had crossed into unfamiliar territory, where words weren’t just words, but powerful catalysts that were constantly scrutinized by our readership.

In the beginning, I had no idea what was appropriate language for discussing gender differences. But it didn’t take long before I was inundated with opinions on the matter.

Fortunately, LGTB organizations provided me with literature and statistical information that aided in my attempt to report Fred’s story with compassion. I was glad to have the help.

One reader kept a running tally of how often I wrote the word “homosexual” in each article, stating that it was offensive, and she was “sure there is a flaw in everyone… and no one wants to bring it out in the open.” Another letter, written by a local pastor, stated that “there is no such thing as gay” and society should not be asked to accept or tolerate gender differences.

Letters defending the gay community poured in, citing the need for tolerance, but many were from people in neighboring communities and from out of state.

Speculation about how Fred’s sexuality played into the crime was plentiful, but most discussions were awkward as people struggled to communicate their thoughts and feelings.

At the vortex of all the chaos – and sometimes forgotten amid the controversy – was a grieving mother, Pauline Mitchell, whose painful loss played out in the public eye.

Maternal instincts

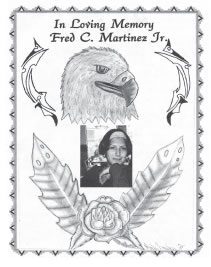

Fred’s funeral program.

I went through three possible phone numbers before I found one that rang through to Pauline’s little trailer at Happy Valley just a few blocks from where her son had lain lifeless days before. She seemed shy by nature, and the trauma of losing her son had sent her into a reclusive state. Our conversation was very brief, and the softly spoken woman asked for her privacy, so I gave it to her. I later learned that she had good reason to have her guard up.

Before long, LGTB activists came to Pauline’s assistance, helping her to issue a written statement that blasted local law enforcement and the DA’s office for violating her rights as a victim.

In the early days of the investigation, Pauline and the police gave starkly different statements about whether or not Fred had been reported missing before he was found. Neither party conceded their stance, and eventually the point became moot, but it was an indication of the sometimes-strained relations between Fred’s family and the authorities.

Even worse, it emerged that the district attorney’s office had neglected to provide her with complete information about her son’s death before they released it to the media, and she had learned the state of Fred’s badly decomposed body via one of my articles.

The DA’s office quickly responded and obtained a gag order on all information pertaining to the case, but it was little more than a gesture at that point.

Months later, Pauline and I met in the hallway after a court hearing for a guilty plea by the perpetrator. Though we’d barely spoken, she hugged me and thanked me for the job I’d done. It meant more to me than any award could have.

Nadleehi

The weeks following Fred’s death saw a frenzied, ever-evolving community discussion about gender identity and the concept of “hate crimes.” According to his mother and friends, Fred identified himself as transgendered – a girl trapped in a boy’s body.

In traditional Navajo culture, Fred was considered “two-spirited,” or “nadleehi,” a man with feminine characteristics. It’s a trait that is celebrated because such people posses the ability to understand the perspectives of both sexes, often earning a position of high respect within their community. Fred’s story later inspired the documentary film “Two Spirits,” shedding more light on the subject.

But Fred lived amongst a dichotomy of attitudes, and not everyone agrees that people such as he are specially gifted. One of the more memorable examples of open bigotry in the wake of his death was a sign in the back of a truck parked outside a forum in Cortez on hate-crime legislation. It read: “God hates fags!”

Homegrown hate

Police and sheriff’s officers pursued the case diligently, and on July 5, 2001, an 18-year-old Farmington man was arrested for the murder. Shaun Murphy, who was eventually charged with first-degree murder, was known by school officials and law enforcement as a troublemaker with a violent past. His record included a variety of charges and convictions, primarily for assault. His demeanor in court did nothing to improve his public image, as he said very little and frequently scowled at the camera. Facing the possibility of the death penalty, he pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and was sentenced to 40 years in prison.

Over the course of multiple court hearings and police interviews, Murphy said very little to answer the question of motive. He and Fred did not know each other prior to June 16, when they ran into each other at the Ute Mountain Rodeo and then crossed paths later near a convenience store. Sometime after that, Murphy left an apartment where he was hanging out with friends and apparently tracked Fred down and smashed the boy’s head with a rock.

Later, he bragged to friends that he had “bug-smashed a hoto” – slang for beating up a gay person.

That detail was revealed July 7, in a court affidavit released at the time of Murphy’s arrest, one that came the day of Fred’s memorial.

On Aug. 16, a vigil for Fred, organized by local and national LGTB advocates, was held in a Cortez park. Judy Shepard – the mother of Matthew Shepard, the gay man tortured to death three years earlier in Wyoming – attended.

The attention the case garnered served as a vehicle for the community to address issues that would otherwise have remained taboo.

The learning curve

It didn’t take long before attention turned to the local educational system and how it had dealt with both Fred and Shaun.

Shaun had been kicked out of middle school, Montezuma-Cortez High School, and eventually the local alternative school for disruptive and violent behavior. The Journal received more than one anonymous letter suggesting that his descent into violence was not surprising.

Fred, in contrast, had dropped out of MCHS as a result of harassment from other students, as well as school policies that appeared to discriminate against individuals with gender differences: He was once sent home for wearing girls’ sandals, for instance.

Fred’s death prompted the school board and school officials to re-examine and revise anti-bullying policies. Early in the school year that followed Fred’s death, the district held an in-service day dedicated to bullying prevention in what I believe was a genuine effort to heal a hurting community.

20/20

My time at the Journal was short, but memorable. I left the paper the next year for a less-controversial career opportunity in magazine journalism.

Ten years later, I‘ve again found myself working in the community, but in a very different capacity. The face of the town hasn’t changed much, though I suspect there have been strides made towards tolerance and acceptance of the gay community. Many LGTB individuals and couples who lived in the area before Fred’s death made their presence known that summer, and continue to live and function in the community as openly gay.

In a post 9/11 and Columbine world, I think Americans in general are more thoughtful about the impact of prejudice and hatred than they were just 10 years ago.

But there are also reports that bigotry is still alive and well, and in some surprising venues. Recently, I heard of a local family who moved away from the area after facing reportedly anti-gay attitudes from personnel at their school.

Although my days as a crime reporter are behind me, I’d like to offer myself one more time as the messenger and sounding board for Fred’s story by posing one question for anyone who’d like to engage in a thoughtful discussion about bigotry and bullying. Have attitudes towards the LGTB community changed in the 10 years since Fred‘s death?

If you have thoughts on the subject, please send an e-mail to freepress@fone.net with “Attention Aspen” in the subject line. Your anonymity will be protected unless you choose to waive it. I hope to report the results in an article this summer.

Editor’s note: The Cortez Journal’s coverage of the Fred Martinez case, led by Aspen Emmett and with contributions from Katharhynn Heidelberg and Jim Mimiaga, was one of five finalists for a national award from PFLAG (Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays).