Voting takes place in secret, but campaigning is done as publicly as possible.

Yard signs such as these are sprouting before the Aug. 12 primary, which features a race for the Montezuma County commission in District 2. Some municipalities try to limit how long such signs can stay up, but such laws have been struck down in other places as unconstitutional. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga.

In the past month, political signs have been sprouting throughout the area. And as the signs pop up, so do rumors of vandalism and theft, charges of signs being put on property without permiission, and complaints about clutter and unsightliness.

So far this year, there have been no complaints to the Montezuma County Sheriff’s Office about signs being stolen or vandalized, according to Underheriff Dave Hart, but the problem regularly occurs.

“It’s not uncommon and we’ve had it in past years, but I don’t think we’ve gotten any reports this year,” Hart said.

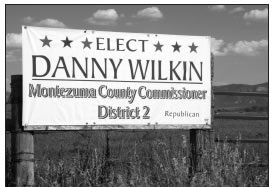

In addition to yard signs, some candidates utilize larger placards such as this 4-by-8-foot one. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga.

However, much of it probably goes unreported, he said, unless there seems to be a regular pattern of one candidate’s signs disappearing or being destroyed.

Hart, who came to the area from Missouri, said similar incidents happen there, too. He said it seems more common for signs involving local candidates to be stolen rather than those for national politicians.

If someone is caught defacing or stealing a sign, he or she can be charged with criminal mischief. What seems like a trivial offense can be a real problem if it happens too often, Hart said.

“It can be a big problem for candidates, because, one, they want those signs up there, and two, it’s costing them money to replace them.”

Most of the signs now showing in Montezuma County seem to be for the county-commission race in the Cortezarea district, probably because that’s the only race on the Aug. 12 primary. Republicans Larrie Rule, the incumbent, and Danny Wilkin are vying for a chance to face Democratic challenger Fred Blackburn in November.

All three men said they never place signs anywhere without obtaining the landowner’s permission.

The majority of signs on display are yard signs, two-sided cardboard rectangles that fit over a square wire frame that holds them up.

Rule told the Free Press he has had problems with his yard signs mysteriously disappearing from various places. Some he believes were certainly stolen because the signs were later found with the wire removed.

“I think the wind got the others,” he said.

He hasn’t reported the apparent vandalism, he said, because it hasn’t been a big problem so far and “I know the sheriff’s department has plenty to do.”

“But it does aggravate me when they’re gone, I’m telling you,” he said.

The small signs cost about $6 apiece, he said. “So far nobody has messed with the big ones.”

Wilkin said he likewise has not had any of his larger signs go missing, but at least two dozen of his yard signs have been taken down. Probably six have disappeared from the corner of Empire Street and Highway 491 alone.

“When they take the metal frame out, it’s vandalism,” he said, adding that he knows the wind gets some other signs.

Like Rule, he hasn’t reported the problem.

“I think you just have to expect it and realize it’s going to happen,” Wilkin said.

Blowing away like balloons

Blackburn, who does not yet have as many signs out as his opponents because he isn’t running in the primary, said he may have had a few signs taken, but most disappearances can probably be blamed on the wind.

“I learned that if the signs aren’t stapled at the base, they blow away like balloons,” he said. “So people think their signs are being stolen. I thought that myself till I figured out it was the wind.”

He said he’s heard that in the presidential race, signs for Democratic hopeful Barack Obama have been disappearing all over, taken as collectors’ items because Obama is the first black to be a real contender.

In his own case, Blackburn said he’s had four instances that he was sure involved vandalism. “When three or four wires are being unwrapped to get a sign off a fence, it’s deliberate,” he said.

Who’s doing the vandalizing? All three men said kids might do some of it, while in other cases, ardent supporters of one person or the other might pull down signs, unbeknownst to the candidate himself.

But if that’s the case, Wilkin said, he wishes they would try an honest approach instead.

“I would rather see people who were going to take political signs put their energy into something positive, by going out and working for the candidate rather than using all negative energy and stealing the signs,” he said. “Get out and support your candidate.”

All three candidates said they do believe signs are important. All have ordered 500 of the yard signs so far. Wilkin and Rule both have larger placards, too, either 3 by 6 feet or 4 by 8 feet. Blackburn has none of the bigger ones and isn’t sure he will get any.

“It’s almost like we’re getting into penis envy with the size of the signs out there,” Blackburn said. “I’m not aware of any studies showing bigger signs are effective.”

However, all three men agree that signs are a critical component of a political campaign.

“How else do you get to 26,000 people?” Rule asked. “If you put your signs out there and they leave them alone, I think it’s very helpful.”

“It’s name recognition,” Blackburn said. “The bottom line is name visibility. Two-thirds of our budget will be in signs.”

People don’t read

Blackburn said he doesn’t believe advertising in newspapers or on the radio is as effective. “We have a whole group of people here who read no papers at all,” he said. “There are people who don’t even know I’m in a commission race. Signs get your name out. It’s more a psychological battle than anything else.”

But just having a lot of signs up is not the only consideration, Blackburn said. “Location is important. So is the design of the sign.” Most — but not Blackburn’s — are red, white and blue. He said those colors are overused. “All the signs are starting to look alike.”

Democrat Galen Larson, who ran for county commission in 2004 but lost to Steve Chappell, said he believes yard signs are a necessary evil, but they can’t take the place of pressing the flesh.

“They’re effective, but I don’t think they have the impact that knocking on doors and shaking hands does,” Larson said. “And they clutter up the neighborhood. People should pick them up after it’s over.”

Blackburn hates thinking about all the clean-up that will be involved after the election. “Those signs need to be removed when it’s over. They’re an eyesore. If there was a better way, I would have never bought signs.”

Any placards for Democratic candidates can be returned to Democratic headquarters in downtown Cortez after the election, he said.

Unpopular opinions

Getting signs up is great for candidates, but showing your colors politically may not always be a good thing for home and business owners, especially for those expressing minority viewpoints.

One Montezuma County resident, who asked not to be named, said she had displayed yard signs for three past Democratic county-commission contenders and all had been removed. She believes it was deliberate because other signs she had up were left alone.

During one presidential election year she also had a swastika put on her window with soap after she showed her support for the Democrats, she said.

Business owners, too, can be leery of showing obvious support for one candidate over another, and some have reported losing business because of their views.

“I will not ask any business to put my sign up because there’s been some heavy (financial) damage done to businesses for Democratic signs in the past,” Blackburn said.

“There are people if you ask them who will put up everybody’s signs because they don’t want to support any single one.”

Constitutional questions

Signs can be controversial in another way: They are often regarded as unsightly.

As a result, some municipalities have regulations restricting the number of political signs in any one place, how long they can be left up, and other factors.

However, some such restrictions skate on the edge of violating First Amendment freedoms and in places have been struck down.

In Cortez, any signs under 3 square feet in area (most yard signs) aren’t regulated. To put up a bigger sign, the candidate must get a temporary permit, which is good for six months, according to Kirsten Sackett of the city planning department.

“We want to make sure they meet setback requirements and don’t obstruct a view on a corner, things like that,” Sackett said.

The permit can be renewed four times and costs $27.50 for signs totaling up to $500 in value.

Dolores has no regulations regarding campaign signs, according to Town Clerk Ronda Lancaster.

In Mancos, no one could be reached who could explain the sign regulations, but Commissioner Rule told the Free Press he had asked to put up some large signs on private property in the town and had been told he could not.

In Durango, regulations require, among other things, that political signs:

• Pertain to a specific election and can be displayed no earlier than 30 days before the election;

• Do not exceed 12 square feet in area and do not exceed more than one sign per parcel for each candidate or issue;

• Must be removed within three days after the election.

Striking down time limits

But restricting how long political signs can be up may be a violation of free-speech protections.

In 2007, a U.S. District Judge struck down regulations in Baltimore County, Md., that restricted how long election signs could be left up in yards. The American Civil Liberties Union had sued, saying the law violated the First Amendment.

After the court decision, the ACLU wrote to other counties in the state advising them that time limits on campaign signs were not legal.

In 2000, the Ohio Supreme Court ruled that a law in the city of Painesville that required taking signs down within 48 hours after an election was unconstitutional, according to information from the web site firstamendmentcenter. org.

In 1999, a federal district court in Maryland struck down a sign ordinance in Prince George’s County that set time limits on election signs in private yards.

And in 1994, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a Ladue, Mo., city law that prohibited signs at private residences. A homeowner had challenged the law after she was cited for putting a 2-by- 3-foot sign in her yard opposing the Persian Gulf war.

Regulations on size, shape and placement of election signs have generally been allowed. And homeowners’ and condominium associations are able to enforce stringent rules about signs in their developments because they are private parties that are not considered “state actors,” as are cities and counties.

Cheap, effective and protected

So, in this age of global telecommunications, Internet, television and text messaging, the venerable cardboard sign remains one of the most effective campaign tools — and it is protected by the Constitution.

“Residential signs are an unusually cheap and convenient form of communication,” the Supreme Court wrote in its 1994 Ladue ruling.

“Especially for persons of modest means or limited mobility, a yard or window sign may have no practical substitute.”