“I am very passionate about it,” says Navajo weaver Roy Kady of his art. “It’s my love. I can feel it at the tips of my fingers.”

Kady grew up in a weaving family in Goat Springs, a small community near Teec Nos Pos, Ariz., where he now lives. His father was the Salt Clan, his maternal grandparents from the Folded Arms Clan, and his paternal grandparents of the Yucca Strung Out On The Line People. Kady belongs to the Many Goats Clan.

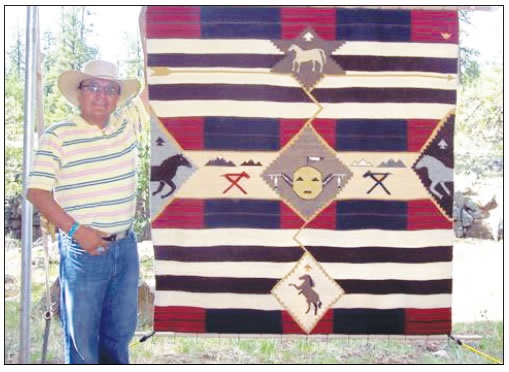

Roy Kady of Teec Nos Pos, Ariz., with his weaving entitled, “The Sun’s Horses.” A mixture of natural colored yarns and vegetal-dyed yarns were used in this weaving.

Both his grandfathers made woven horse implements and braided rope. One grandfather knitted ceremonial socks and bags. Kady began learning to weave from them.

This is not unusual. Navajo men have always knitted and woven. “If we go back to the Creation Story, it tells how Spider Man helped (Spider Woman) set up the loom and instructed her in the weaving process,” Kady said. “He asked her to teach the rest of society how to weave.”

Women became known as weavers because in Western literature, the weaving story is told from Spider Woman’s perspective. Also when the U.S. Cavalry arrived at Navajo homesteads, they found women at the looms because the men were out hunting.

Kady’s grandmother shared with him her knowledge of vegetable dyes, as well as how to create plain and twill patterns. As he reached his teens, his mother helped him refine these techniques.

“So I kinda consider myself a fourth generation, but I may be mistaken. I haven’t researched further back,” he laughs, explaining that weaving in his family may extend to the days before the Spanish brought sheep to the Southwest, and the Navajo wove with wild cotton, tree and shrub bark, and yucca fibers.

The Spanish brought churro sheep. “It’s the sheep of choice for ’round here,” says Kady. “It actually thrives on the land.”

The churros eat plants at any elevation, and have evolved to require specific nutrition at specific times as herders drive them from winter camps in the valleys to summer camps in the mountains.

“When you get to encounter one, it still has a kind of wild instinct. It’s a true survivor,” Kady says.

After switching to churro wool, weavers created blankets and rugs as they always had, in bold striped patterns, employing four basic designs found in the Creation Story. Colors reflected the roughly 16 shades of black, gray, brown, red, or apricot found in their animals.

Always mindful of the traditional cardinal directions, the weavers referred to the colors of their fibers as white shell and white cloud to the east; turquoise shell and blue cloud to the south; abalone shell and red cloud to the west; and black jet stone and black cloud to the north. To supplement these hues and create bright pastels, they employed tea from plants gathered as they herded sheep between camps.

After Kit Carson force-marched the Navajos on the Long Walk to Fort Sumner, N.M., other breeds of sheep became available to weavers. So did new designs, as traders needed rugs to sell to Eastern tourists and collectors, and encouraged new motifs.

While everyone used the twill and plain weaves, regional styles emerged in communities such as Two Grey Hills, Teec Nos Pos, Ganado, and Klagetoh.

Now weavers, including Kady, research the history of these patterns, recombining them in new ways. “Our styles are unique to our interpretation. Some of them are tied into the stories.”

Kady’s designs relate to his environment and family. His grandfather kept more than 100 horses for plowing, hauling, or dragging logs to build homes. “He knew where every single one was at, and he rounded them up.”

Kady’s mother transported him and his siblings on horseback. Today, Kady uses horses in many of his weavings. “It’s just a creature that is one of the sacred animals like the sheep.”

He likes to create storytelling rugs around the sun horse, depicting the steeds the sun rides as its day progresses. He might see a band of wild horses and the weaving becomes “Horse Song.” The horse song describes horses, their food, and the four mountains sacred to the Navajo.

Sometimes the landscape inspires him as he herds his sheep. He’ll design a weaving with a background of mountains, valleys, and often the heavens. He employs lightning zig-zags or backwards swastikas to imply motion. Family stories become the basis for designs.

Kady creates his weavings in the traditional Navajo way, spending summers herding churros from the valley to the mountains so they can eat the balance of plants required to give them “healthy luscious wool.”

In the fall he shears, cards, and spins the wool into yarn, often mixing in alpaca or llama hair for strength, and to make the yarn silky to the touch. After choosing natural colors and creating hues from plant dyes, he strings his upright loom and weaves.

Traditional weaving is a long process. Many weavers no longer do it, turning instead to the more convenient commercial dyes or commercially dyed yarn.

“I am definitely privileged and honored to continue that process,” says Kady. “It was taught to me that weaving is a gift you were given, and to pass it on.”

He passes his knowledge on during workshops, lectures and exhibits around the world.

In Teec Nos Pos, he gives free weaving classes on Tuesday evenings.

“Wherever the road leads, that’s where I’m at. That’s where my sheep and my weaving take me.”