Love them or hate them, roundabouts are fast becoming a fixture on the Western Slope. The traffic-control devices long ago popped up in Grand Junction and Durango — and have begun appearing in points between.

Now, with Telluride poised to construct a first-of-its-kind traffic circle on Colorado 145, and the city of Cortez considering one for Mildred Road and Montezuma Avenue, roundabout-shy drivers may just have to get used to something new.

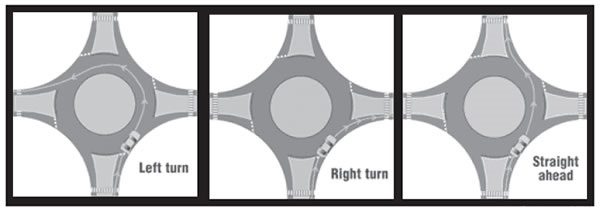

These illustrations show how vehicles maneuver through a roundabout. The modern traffic-control devices, which are completely different from older traffic circles, have no signals and are designed to keep traffic flowing, thus reducing idling time and pollution. They are popular in many countries but are slow to catch on in the U.S. Photo courtesy of IIHS

“I love them,” said Cortez resident Ric Plese. “I think they’re efficient. You don’t waste a lot of gas; people are always moving and not idling.” Further, he said: “It’s cheaper than a stoplight.”

Plese’s views are similar to Telluride’s rationale for constructing a roundabout at “Society Turn,” the three-way intersection on Colorado 145 where a spur goes east into the mountain town. At present the northbound drivers coming down off Lawson Hill come to a stop at a stop sign where they may turn right (east) into Telluride or left toward Montrose. Traffic moving straight into and out of the town does not stop, and the intersection is among the most hazardous in the state, according to Telluride Mayor Stu Fraser.

The town has signed a contract with the Colorado Department of Transportation, and had expected to mail a check by the end of November, he said. Construction is to start after the last of the freeze-melt weather, likely in April. During construction, traffic will be routed through Colorado’s first temporary roundabout on a state-maintained highway.

The permanent roundabout is to feature a built-in de-icing system — the first on a roundabout in the state highway system, said CDOT spokeswoman Nancy Shanks. (Some bridges have de-icing systems, she said.)

“Obviously, Telluride is unique — it’s at a very high altitude for a roundabout. It will definitely need assistance in de-icing measures.

That will be a great feature,” Shanks said.

Cortez, for now, is only in the talking stages about installing a roundabout at Mildred and Montezuma. A traffic circle is just one of several ideas being considered, city officials say, and they are seeking comments on the proposed intersection-improvement project.

“They’re coming into popularity,” Cortez Public Works Director Jack Nickerson said of roundabouts, citing Telluride’s project. “It’s a fully functional intersection and you get more traffic through” with a roundabout.”

According to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, studies in the United States have found that roundabouts reduce motorvehicle crashes by 37- 40 percent and injury accidents by 75-80 percent. In addition, the IIHS says roundabouts improve traffic flow and therefore reduce fuel consumption as well as air pollution.

Not everyone’s a fan, though. “They seem to cause confusion for people,” said Montezuma County resident Lisa McCoy.

McCoy formerly lived in Boulder and California, where roundabouts proliferated. The traffic volume and multiple lanes in one California traffic circle created “a nightmare,” she said.

“In this area, that is going to cause road rage,” McCoy said. And when it comes to getting across the four-way intersection at Mildred and Montezuma: “I just can’t see that would make it easier. I haven’t had any real positive feelings about [roundabouts].”

According to the IIHS, roundabouts were first designed in the 1960s in the United Kingdom and have spread worldwide; the first one in the United States were built in the 1990s, and there are presently about 2,000 nationwide.

U.S. roundabouts require vehicles to move counterclockwise around a center island. The tight curves force vehicles to slow down (to 15-20 mph for urban roundabouts, 30-35 mph for rural roundabouts), thus increasing safety.

“At traditional intersections with stop signs or traffic signals, some of the most common types of crashes are right-angle, left-turn, and head-on collisions,” states the IIHS on its web site, www.iihs.org. “These types of collisions can be severe because vehicles may be traveling through the intersection at high speeds.”

Such types of crashes are eliminated with roundabouts because vehicles are moving in the same direction, according to the IIHS.

The crashes that do occur usually involve vehicles merging into the roundabout, and tend to be less serious because of the slow speeds. Rear-end collisions are also reduced in number and severity because drivers aren’t zooming ahead to make green lights or throwing on the brakes when a light changes.

Good design makes all the difference, said Ned Harper of Dolores. He said he’s familiar with roundabouts, having driven on a fair number in Europe, where the devices are common.

“I do not like the intersection at Montezuma and Mildred, and I do know that I’ve driven a lot [of roundabouts] in Europe,” Harper said. “They seem an easy way to deal with the problem.”

He said he is less enthused about the traffic device outside the Mercy Medical Center complex east of Durango, on the northern side of U.S. 160, because it doesn’t seem well designed. “It shows America’s lack of familiarity with them,” Harper said. “I don’t think it’s a very good one.”

But practice makes perfect. “Like anything new, it takes getting used to. But it’s not a big deal, if it’s well done,” Harper said.

Roundabouts definitely can be confusing to drivers encountering one for the first time. There are no traffic signals, and it can be unclear where one goes to turn left or head straight.

“It takes some people a while to get the knack of them,” acknowledged Plese. (General hint: look left when entering a roundabout and remember that vehicles already in the roundabout have the right of way.)

But traffic engineers are enthusiastic about the devices, saying they have many benefits and very few drawbacks.

“Roundabouts are safer than traditional intersections for a simple reason: By dint of geometry and traffic rules, they reduce the number of places where one vehicle can strike another by a factor of four,” states a 2009 article in the online magazine Slate. “They also eliminate the left turn against oncoming traffic — itself one of the main reasons for intersection danger. . . . The fact that roundabouts may ‘feel’ more dangerous to the average driver is a good thing: It increases vigilance.”

Roundabouts are also generally judged to be safer for pedestrians because people on foot do not cross multiple lanes of traffic moving in different directions, according to the IIHS. Instead, they cross only one direction of traffic at a time and generally cross fewer lanes at a time.

However, the benefits for cyclists are less clear. Some studies have found that bicycle crash rates are not reduced by roundabouts and may even be increased, according to alaskaroundabouts.com. Many new roundabouts therefore include bypasses for cyclists that allow them to maneuver the intersection without joining the vehicles in the roundabout.

There are also concerns about the impacts of roundabouts on the visually impaired, who may be understandably reluctant to cross a street without some sort of traffic signal. It is possible to install signalized pedestrian crossings on each road connecting to a roundabout, but this greatly increases the cost of the roundabout and also prevents the free, continual movement of traffic that is one of the device’s benefits.

It’s important to note that modern roundabouts are very different from older traffic circles, which had confusing rules and different designs along with often-poor safety records. The primary difference between the two is that in modern roundabouts, entering traffic always yields to traffic in the circle. In old traffic circles, entering traffic was controlled by stop signs.

“To me, they’re pretty straightforward,” Nickerson said. “We have a roundabout at Brandon’s Gate [subdivision]. If they’re not designed big enough, it can be difficult for trucks to get around. But that will be handled in the design process.”

Brandon’s Gate has little traffic, as the subdivision is not fully developed. For busy Montezuma and Mildred, Cortez needs to perform a study of traffic flows, including different turn movements — the number of right and left turns, etc. — to determine “warrants.” So many right turns warrant a right-turn lane; so many left turns would warrant a left-turn lane, explained Nickerson. Additionally, the traffic study would be used to determine when traffic flow is highest during the day.

Nickerson says the study might also look at whether to change the grade of the hill on Mildred Road. “We would like to improve the sight distance, particularly improving Main Street coming up the hill,” he said.

But why a roundabout — why not keep the current four-way intersection, or install a traffic light?

“We know a signalized intersection presents some immediate pitfalls in that we could back traffic all the way back to Main Street,” said Nickerson. He added, however, that the traffic study must be completed before city officials will know for certain.

With a roundabout “we won’t have a signal to maintain. You can get more traffic into the intersection,” Nickerson said.

Another option is to close both left-hand turn lanes at the four-way. People turning left would line up with those driving straight across the intersection. The right-hand turn lanes would remain. Nickerson reiterated that the research necessary for this option has yet to be done.

“That would by far be the cheapest solution,” he said.

But: “It doesn’t really solve the traffic flow problem,” he added. “The problem with the intersection is you have a total of six options, with Montezuma hitting Mildred at all sides. A four-way works best when only one lane is going into an intersection. Right now, we would like to keep Mildred as free-flowing as possible.”

How much nearby park space a roundabout might gobble up is something Nickerson says he can’t comment on.

“We would have to look at how big of a radius we would need for a roundabout,” he said. “If we do place a roundabout, we would have to place the crosswalks beyond the roundabout, so there would be some [work to do there].” He said as far as he knows, the impact would be minimal.

The requisite traffic study is projected to cost $10,000, and is slated to go out for bid early next year. After that, the city plans to slate public meetings concerning preferred alternatives and their costs. No construction would occur before 2013.

Construction costs themselves depend on what option is selected, and if a roundabout is chosen, cost depends on its design.

“Telluride is looking at $2 million to $3 million. But they’ve got all the bells and whistles,” Nickerson said.

Telluride’s move toward traffic circles began several years ago, when the Colorado Department of Transportation suggested a roundabout to deal with the 10,000 vehicles Society Turn saw daily, Fraser said. Town leaders then researched that option.

“It ended up that we agreed,” he said. “It is longer-lasting, safer, more environmentally friendly because you don’t have cars sitting at a signal, and you don’t have people racing off. There were a bunch of reasons why it made more sense.”

The town has already built a small roundabout on Mahoney Drive in town, to deal with traffic backlogs near the school.

But talks on the Society Turn roundabout went silent until a few years back, when a poorer CDOT came back to town leaders with an offer to build a signal at the problem intersection instead.

“Our reaction to that was, no, we don’t want a signal. We want a roundabout. We know in the long term it is a safer decision,” Fraser said.

Telluride will pony up about $900,000 to add to the $1.3 million price tag. Fraser said Mountain Village and San Miguel County were originally on board to split the cost three ways, but budget constraints have since precluded that. Now, San Miguel County could pay $200,000 toward Telluride’s share, and Mountain Village might kick in $25,000 or more, Fraser said.

A plan to deal with the intersection is long overdue, he said.

“During busy times, you’ve got people guessing as to when is the best time to cross over. We look at this [from] the point of view of safety as a major factor. Otherwise, why would we be doing any of this?” Fraser said.

“It’s not an emotional issue. Some people say it’s just aesthetics. But overriding for me, a roundabout is far and away the best trafficcontrol mechanism that exists for us.”

Whether a traffic circle is the best option for Mildred and Montezuma remains to be seen. “The traffic counts may say we do nothing for 10 years,” Nickerson said. “We’ll do the study and we’ll move on from there. But I will say that intersection probably generates the most complaints in town of any of the intersections that we have.

“We’re just trying to plan for the future a little bit.”

To comment on the proposed project, visit the public-works office at 110 W. Progress Circle; call 565-7320, or email Nickerson’s assistant, Donna Thompson, at dthompson@ cityofcortez.com. Put “Roundabout” in the subject line.