Drive over Wolf Creek Pass, and you’ll notice a grim reality: most of the mountain’s centuries-old spruce trees are dead and gone. To a casual onlooker, the trees appear to have died within the span of a single year, though in reality their demise has been brewing for nearly a decade. The culprit: spruce beetles, the latest in a succession of barkbeetle attacks that got their local start with the extremely dry years of 2002 through 2004.

Years-long scourge

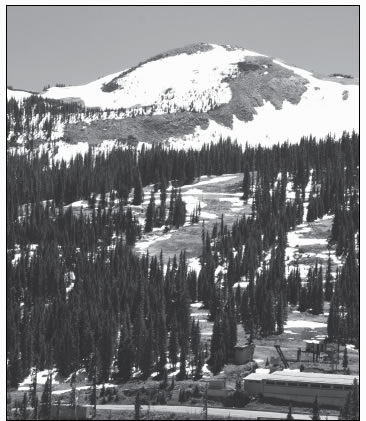

The spruce trees that give Wolf Creek Pass so much of its beauty are being hard hit by bark beetles, although these stands near Wolf Creek Ski Area have not yet seen much damage. Up to 90 percent of Engelmann spruce in Colorado’s highest-elevation forests are believed to have fallen to the spruce beetle. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

Steve Hartvigsen, supervisory forester with the Pagosa District of the San Juan National Forest, says it’s a common misperception that there’s a single bark beetle chomping its way through our forests. He says the wave of damage began as drought peaked in the region. The first outbreak involved the Ips beetle, which attacked piñon pines.

“It killed a lot of piñon pine in Cortez and northern New Mexico,” he said. “That was the first real epidemic of bark beetles, and it was before the lodgepole attack in the northern part of the state.”

Soon after, white fir came under attack by the fir engraver beetle in the eastern San Juan Mountains and northern New Mexico.

“At the same time we were starting to see on the San Juan the western pine beetle attacking ponderosa pines, especially north of Durango. Mountain pine beetle, that’s the one that’s really kicking the lodgepolepine butt,” he said, adding that two or three bark beetles – including the poplar borer, the bronze poplar borer and “some other mystery borer” – were factors in Sudden Aspen Decline, or SAD.

There’s yet another beetle attacking Douglas fir trees. Though the damage hasn’t been dramatic, it’s proved an unfortunate hit to Douglas fir stands that were thinned rather aggressively, in retrospect, decades ago.

But by far the worst plague has been the spruce beetle. According to a 2010 report put out by the state, “The Health of Colorado’s Forests,” up to 90 percent of Engelmann spruce in the state’s highest-elevation forests have fallen to that particular bug.

Feeding frenzy

Hartvigsen said whereas drought was the major force that set the stage for many of the earlier bark-beetle outbreaks, a huge avalanche cycle in 2005 and subsequent highwind tree blowdowns created perfect host habitat for the spruce beetle.

On the highly visible Wolf Creek Pass, the combined hits have been killing spruce trees for up to eight years, but it wasn’t until this year that people have been noticing, he said. That’s because even as their needles yellow and fall off, a green lichen that grows on the trees can disguise the damage.

“It’ll take years sometimes before the crown starts to show that attack,” Hartvigsen said. “It was this year that people started saying, ‘What happened in the past year?’”

Many of the other spruce trees dying from the scourge are in the high backcountry, he said; even the regular Forest Service helicopter surveys didn’t start noticing the destruction until years after trees began dying.

But there’s no mistaking the places where spruce beetles have come and gone. Henry Hornberger, general manager of southern Utah’s Brian Head Resort, said when he arrived there 16 years ago, spruce beetles had already been at work and the trees, though still standing, were dead and dying.

“Sure enough, within the next two years a lot of the trees dropped their needles,” he said. And in the years after that, the Forest Service held several timber sales. The wood was actually salvageable, and useful in the housing boom then in full swing. Both the resort and the town of Brian Head were active in removing damaged trees, Hornberger said.

“We lost a ton of trees, but the silver lining is it opened up more skiing,” he said. “All the areas that were harvested were replanted with seedlings. We’re not going to see mature trees in my lifetime.”

When Brian Head lost its spruces, many of them hundreds of years old, they also lost their most effective windbreaks.

“We’re a lot more susceptible to wind closure on our lifts,” Hornberger said.

Cleaning up and clearing out

Wolf Creek Ski Area is now seeing what Brian Head did nearly two decades ago, said Davey Pitcher, Wolf Creek’s CEO and mountain manager.

Pitcher said staff at Wolf Creek began cooperating with the Forest Service in the late 1990s to remove trees bowled over by wind, so as to remove spruce-beetle habitat. Still, “we’re probably looking at 60-70 percent mortality on the pass,” he said. “It’s going to be significant to some of the skiing patterns.”

Until last summer, the resort was spending $100,000 a year to remove dead and downed spruce trees, so spruce beetles wouldn’t have a place to hole up. Last year, there was too much to handle, so this year’s management agenda involves extensive collaboration with the Forest Service to get rid of the damage.

Pitcher said Wolf Creek has a long-standing philosophy of maintaining a natural environment; on many runs they stopped cutting trees or even grooming the runs a decade ago. The difference following the spruce-beetle outbreak is that there are few remaining large, old trees to provide shade, windbreaks and visual aids for depth perception on cloudy days.

Now, spruce saplings are growing up in the open spaces. The challenge going forward is education, he said – so skiers and snowboarders don’t accidentally lop off their tops. That will make the difference between regenerated spruce stands in half a century – or a permanent legacy of stunted and deformed bushes along the slopes. Skiers will have to be careful for quite a while: San Juan’s Hartvigsen points out that it takes an Engelmann spruce tree 45 years to reach a height of 4 1/2 feet – that is, to reach from the seedling stage to the top of the snowpack.

Natural progression?

Wolf Creek’s Pitcher says he’s had an emotional response to the mass die-offs of spruce trees on the pass.

“It’s been pretty sad for me,” he says. “A lot of these trees, you kind of think of them as being immortal. Seeing them get hammered by these creatures, it’s hard. My daughter, who’s in college, has grown up watching it and is a bit more philosophical about it. She sees it as part of the natural pattern of things.”

Whether the beetle kills of the past decade or more are natural, says Tom Eager, an entomologist with the Forest Service’s Forest Health Management program in Gunnison, is the “beer debate” at entomologists’ conferences.

“That’s one of the hot topics that people go round and round and round on,” he said.

The San Juan’s Hartvigsen says fire-scar surveys have revealed about 140 years of fire exclusion in the region’s forests. He suspects that if fires had been allowed to burn, “we would have punched holes in the canopy that would have disrupted what is now a homogenous, beetle-bait forest,” he said. “We suspect the epidemic levels of spruce beetle on the San Juan is higher than it’s ever been in history because of fire exclusion. I think the intensity and expanse of this sprucebeetle epidemic is greater than it would have been. We can’t prove that.”

Therein lies Eager’s own view: no one, as far as he knows, has shown that today’s outbreaks are unprecedented or unnatural. He recalls a special session at one such meeting, the 2009 Western Forest Insect Work Conference.

The session was called, “Are Current Insect Outbreaks Unprecedented? What Can History Tell us?” Researchers looked at outbreaks of whitebark pine beetles in central Idaho, mountain pine beetles in the Black Hills, four major beetle species in British Columbia, and spruce-beetle outbreaks in Colorado and Utah through the lens of history.

“They weren’t able to say these outbreaks were unprecedented,” says Eager of the findings, which are also available online.

Eager says when he started his career as an entomologist, his early research focused on his observation that most of the forests in Southwest Colorado were in a late successional stage – that is, they were old.

“There were probably events happening 250, 300 or 400 years ago that started this cohort off,” he said, adding that Southwest Colorado’s cohort – or group – was ripe for a fall.

Eager believes it’s that reality, rather than any impacts of climate change or human activities, that has contributed most to the widespread beetle kills.

“I spent the early part of my career saying, ‘There’s a big beetle thing coming’,” he added. “It seemed obvious to me that something was brewing … and eventually we were going to get to the point that we were going to have a recycling of the forest.”