My husband and I were walking along a sidewalk in Grand Junction, Colo., a few weeks ago when a man standing nearby shouted, “Freedom!” at the top of his lungs as we passed.

Startled, we turned back to look at him. “If you keep going in that direction, you’re against freedom,” he warned.

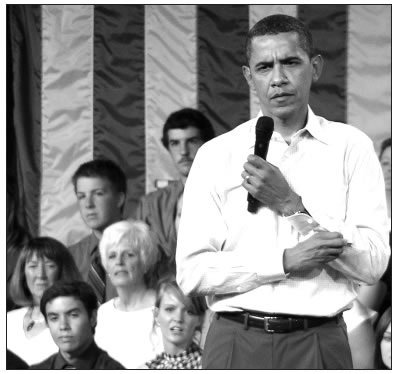

President Obama faces questioners at a town-hall meeting before a crowd of 1,600 in Grand Junction on Aug. 15. Photo by David Grant Long

“Uh, OK, thanks,” I said uncertainly, and we kept walking.

We were headed to Central High School for the Aug. 15 town-hall appearance of President Obama. It was several hours before the event, but even so, we had been forced to park at a shopping center nearly a mile away. When I ducked in to use the restroom at the mall there was a line of women, one of whom told me excitedly, “We’re going to the rally!”

As David and I neared the high school, we encountered protesters with signs such as “Our soldiers didn’t die for socialism.” On the other hand, there was a thick cluster of people at the traffic light in front of the school being led in a chant by a woman with a loudspeaker. “President,” she’d shout, and the crowd would reply, “Obama!” “Reform!” “Now!”

Getting our press passes just involved giving our names to someone who checked a list and handed us each a laminated, hand-written card and a safety pin to fasten it to our shirts. We found seats among the other press people — most of whom seemed very young — at the side of the gym.

I had a quivery knot in my stomach. The President’s decision to come to the highly conservative Western Slope of Colorado to tout health-care reform seemed a little reckless. Sure, there were metal detectors and Secret Service agents, but what if one crazed person rushed the stage and a melee ensued? As David and I waited, I pictured increasingly bizarre but disastrous ways in which someone without a metal object could wreck havoc. Someone could take a match and start a fire. . . or hurl objects at the stage, like the famous shoe-throwing at George W. Bush. . . People might start fighting as if in some barroom brawl. . .

David, on the other hand, was serene. “This isn’t like the town halls with senators,” he reassured me, pointing at a few of the numerous Secret Service agents.

Eventually the gym filled with about 1,600 people chattering restlessly and craning their necks for the first glimpse of the President. There was an invocation, the Pledge of Allegiance, the national anthem. The Secret Service agents paced ceaselessly up and down throughout, but some held their hands over their hearts as the pledge was spoken.

There was another lull, during which late-arriving press people scrambled to find places to set up their laptops (most of which, as far as I could see, were used for nothing but surfing the Net throughout the event).

Suddenly, an enormous cheer erupted from the people on the floor. Some of the dignitaries had obviously walked in, but from our side of the gym we couldn’t see them. Was Obama with them? I wasn’t sure. There had been no “Hail to the Chief,” no announcement.

A man named Nathan Wilkes stepped to the podium and described his experience with the health-care system. An electrical engineer from back East, he said, neither he nor his wife has ever been uninsured, “yet despite these facts we face numerous struggles because of the cost of our health care.” His second child, a boy, was diagnosed with hemophilia when he was born, Wilkes recounted. The family had good insurance through Wilkes’ employer, but as the claims mounted, the insurance company hiked premiums for all the company’s employees. Eventually the Wilkes family reached their cap for coverage and the insurer would pay no more.

Wilkes was paying about $25,000 a year out of pocket and bills were mounting. A social worker suggested the couple divorce so Wilkes’ wife and son could go on Medicaid and enter the state’s pool for high-risk clients, but it also had a cap, and the couple didn’t want to divorce anyway.

“I know our country needs health insurance reform,” Wilkes said, to tremendous applause. Then he introduced Obama.

A protester greets people coming to the Obama gathering in Grand Junction. Photo by David Grant Long

When Obama came to the podium, an unearthly roar rose up. Its intensity lifted the hairs on the back of my neck. People were standing, yelling, pounding their hands together. I tried to think skeptically: How had this audience been picked? Supposedly they were chosen at random from people who applied on-line. If so, not many naysayers had applied, because this crowd could not have been more excited or more welcoming.

Does every president get such a reception? I wondered. Obama is only the third president I’ve seen in the flesh. The first, John F. Kennedy, came to Colorado Springs back in 1963. I was so young I just remember him waving from his convertible (in those innocent days) as he drove past. Later I saw Ronald Reagan meeting with athletes at the U.S. Olympic Center when I was a sports writer in Colorado Springs, but I didn’t see him in front of a big crowd.

Surely all presidents at the height of their popularity do get the proverbial rock-star reception, yet it still seemed that there was a different element here, an extra excitement, perhaps because Obama represents the first person to break the White Male Presidents Only barrier, perhaps because he seems to offer sunny optimism and hope instead of fears and threats.

At any rate, after introducing the Colorado dignitaries present (Gov. Bill Ritter, Senators Mark Udall and Michael Bennet, Rep John Salazar, and Grand Junction Mayor Bruce Hill), Obama launched into his health-care speech.

When you hear tales of people victimized by bad or nonexistent coverage, Obama said, “Remember one thing: There but for the grace of God go I. This is something we have sometimes forgotten in the course of this health-care debate.”

Obama soon doffed his suitcoat and stood before the crowd in a white shirt and brown pleated slacks, a trim, almost slight figure. He was interrupted numerous times by applause, sometimes when he clearly did not expect it.

“We’re going to fix [this] when we pass health-insurance reform this year.” Big applause, one boo.

“Health-insurance reform is a key pillar of this new foundation.” Applause.

“No one in America should go broke because they get sick.” Applause.

Obama criticized the media, TV in particular, for focusing on tempers flaring rather than town halls that go well. He spoke of his town hall in Bozeman, Mont., the previous day, saying it was a mixed crowd that asked tough questions, “but Montanans didn’t shout at one another. They were there to listen.”

The Grand Junction crowd certainly listened as Obama outlined his proposals, which include what he called “a common-sense set of protections” for people with health insurance. For instance, there would be no arbitrary cap on the amount of coverage someone can receive. Currently, he noted, when you hit the limit on your private plan, “it’s suddenly like you have no insurance at all.”

Companies will also be stopped from canceling coverage because someone gets sick or denying coverage because of someone’s medical history, Obama said. In the past few years more than 12 million Americans have been discriminated against because of pre-existing conditions, he said.

In addition, insurance will have to cover preventive care that saves lives, such as mammograms and colonoscopies, he said.

People who like their current private plan can keep it, he said, but there should be a public option available as well. People don’t want government bureaucrats meddling in their health care and neither does he, he said, “but I don’t want insurance-company bureaucrats meddling in your health care, either,” a line that drew a raucous cheer and a standing ovation.

There were a few dissenters in the gym. One man emitted a huge boo after Obama said that when he walked into the White House, “I had a gift wrapped and waiting for me at the door — a $1.3 trillion deficit.” But what was the man booing — the deficit? Obama mentioning the deficit? It was unclear.

Several audience members posed skeptical questions. University of Colorado student Zach Lahn asked how private insurance companies could compete with a government- run plan. Obama said the public option would have to operate as an independent nonprofit not subsidized by taxes

A Colorado Springs business owner named Julie, a Republican who voted for Obama, she is a good employer and a community volunteer. “Why is what we do now not enough?” she asked.

Obama said under his plan, small business owners who already offer health benefits will gain because they will receive government subsidies. If they aren’t offering health benefits, however, they will have to make a contribution.

The questions did nothing to dampen the enthusiasm of the crowd, which applauded fervently as Obama made his exit, and kept clapping to the beat of John Phillips Souza.

As we headed back toward the street, we passed another clot of protesters at the intersection, some pro- Obama, but many anti. “Obama crushing the American Dream one freedom at a time,” read one huge banner. “My freedom’s not for sale. Is yours?” asked another.

The words of the old Buffalo Springfield song sprang irresistibly to my mind: “There’s battle lines being drawn/nobody’s right if everybody’s wrong. . ./Singing songs and carrying signs/Mostly say, hooray for our side.”

As we headed toward our car, we began passing a long stream of people walking toward us. Most were holding signs at their side. We deduced they were protesters who’d lined the street in hopes of being seen by Obama as he passed (Obama’s motorcade did not take that route, however).

They seemed to take heart as they encountered the crowd emptying from the gym, and held their signs up again. Many warned against socialism. One young man dressed in Colonial-era garb carried a copy of the classic “Don’t tread on me” flag. We passed four men in their 20s, all lean, their heads shaven, eerily identical. But the dissenters mostly varied widely in age and appearance. There were at least a couple hundred who passed us.

As we approached one group, a man among them muttered darkly to his companions, “Just look at them. You can tell what kind of people they are.”

They were looking at us. I turned to see if there was anyone behind us, but there wasn’t for a long way.

I glanced over at David in his blue jeans and long-sleeved shirt. I was in jeans and a striped blouse. Neither of us had any sort of slogan or sign on our clothing, no pink hair, no nose rings. What kind of people were we? I wondered. But I was too chicken to ask.

Supporters of Obama’s health-care proposals show off their signs. Photo by Gail Binkly

Farther on we passed a group of teenage boys capering about and holding up signs. They read, “Standing together for health insurance reform” on one side, “Thank you” on the other (for cars that honked).

Obama’s town hall had left me without a clear sense of the area’s overriding sentiments regarding health-care reform, so when I learned that Colorado Sen. Mark Udall had scheduled a town hall in Durango on Aug. 27, I decided to attend. I didn’t bother with press credentials but figured I’d hang out with the crowd.

The event was set for 1 p.m., but people began lining up outside the La Plata County Courthouse well before noon. Again, there were many clashing signs. Although the topic of the meeting was ostensibly energy, most of the signs involved health care.

“Free men are not equal and equal men are not free,” explained one sign. “Only slaves are equal — equally miserable.”

“Government takeover: Kennedy’s dream, America’s nightmare,” read another. (Sen. Ted Kennedy had just died.)

Others took the opposite view. One sign said, “I don’t hear senior citizens and our veterans wanting to get rid of their socialized government programs!”

And a woman in a purple robe held a placard stating: “Jesus healed people with pre-existing conditions. Health care reform now.”

It was apparent that the crowd was as deeply divided as the one in Grand Junction, but the Durango crowd was mellow, and the pro-reform people clearly outnumbered the opposition. People were polite in line, shuffling patiently into the courthouse. It soon became obvious that not everyone would make it inside, and there was grumbling about why the event had been slated for such a small venue.

Organizers put loudspeakers outside so that Udall’s remarks could be heard, but after he’d talked about energy for 10 minutes, the speakers began cutting out.

“Electronic failure — that way we’ll all disperse,” mumbled one man. And indeed, many of the 200 or so seated on the lawn began to leave.

When someone asked about pollution from Chinese power plants, the loudspeakers cut out again and the crowd groaned. The speakers began failing more and more, until they were silent most of the time, with a few tantalizing words getting through now and then.

A middle-aged woman carrying a small flag became annoyed and stomped off, yelling, “If they can’t get this to work how can they take care of our health care? God bless America! Hold it at the fairgrounds next time!”

The sound came on and cut out again, to be replaced by weird electronic moaning and squealing noises.

“Sounds like they’re kissing in there,” someone said snidely.

One of Udall’s aides announced that the senator would come to the courthouse door to address the outsiders remaining. When he appeared, he said the crowd inside had been civil despite “clearly different points of view.”

A few people began chanting, “Health care now!”

“We’re going to get health care!”

Udall replied, to which a man yelled, “Who’s going to pay for it?”

“You are!” someone yelled back, and there was general laughter.

Udall left and the crowd drifted away.

It was a far cry from the heated, even hateful town halls that have been shown on television recently, with people booing senators and congressmen so loudly that sometimes nothing else can be heard. Clearly there is a sizable contingent opposed to health-care reform, but are they in the majority? And are they truly concerned about health care per se, or is the entire debate about something larger?

I thought of the man saying, “You can see what kind of people they are.” He, at least, seemed to view the healthcare debate as a culture clash, which is probably valid. The peculiarity is that those who voice the most patriotism, the most love of country, seem to simultaneously be the most deeply afraid of government — and those who are the most anti-authoritarian expect the government to take the largest role in caring for people’s needs.

“I worry that we’ll end up in a civil war,” one friend e-mailed me recently. But this political divide has been around since the Vietnam War, and somehow the country has survived.

When David and I were driving home to Cortez after the Grand Junction town hall, thinking about the complexities of the health-care debate and the contrast between Obama’s welcome inside and the protesters outside, we heard on the radio a news summary of the day’s events.

“President Obama came to Grand Junction today for a town hall designed to defend his embattled health-care plan, which has drawn heated protests at gatherings across the nation,” it said.

That was it. No pros and cons, not even a basic explanation of what the “embattled” plan might entail. Apparently, despite the crowds and demonstrators, the story didn’t justify that much coverage.