At best, look for a warmer, drier Four Corners region in the next century. At worst, expect severe droughts and water wars.

That was the message given by Dave Gutzler, professor of meteorology and climatology at the University of New Mexico, to a crowd of close to 150 on Jan. 16 in Cortez.

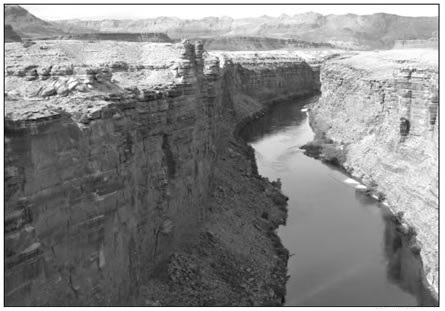

The Colorado River (shown here by Lee’s Ferry and Navajo Bridge) may lose up to 30 percent of its flows in the next century, researchers project. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

The presentation was part of the annual Crow Canyon Archaeological Center Lecture Series, sponsored by Crow Canyon and a number of local businesses.

Gutzler, who has been with UNM since 1995, has a doctorate in meteorology from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He is a direct advisor to the New Mexico State Engineer’s Office and co-chair of a working group on drought prediction.

Gutzler’s talk was low-key rather than alarmist, and he acknowledged that there is “lots of uncertainty” in projections created through computer modeling.

But he believes climate change is occurring, most of it is human-caused, and smart people will plan better ways to manage shrinking water resources.

For instance, streamflows on mainstem rivers in the Four Corners are projected to dwindle significantly in the next hundred years — about 30 percent from 1995 to the end of the 21st century, Gutzler said.

“If this happens, the Colorado River Compact [which governs Colorado River allocations in seven states] would smply be unenforceable,” he said. “We’ll have a water war in the West because we won’t have enough water in the basin to satisfy all the states’ legally apportioned water rights. This is a problem and we need to start planning for this.”

Gutzler presented evidence supporting global warming, but rather than talk about rising oceans and shrinking ice caps, he focused on how the changes are likely to affect the Southwest, which is “what geographers call a climatically vulnerable place.”

Some of the key evidence of a global warming trend:

• The 10 warmest years on record (since weather records were kept) have all occurred since 1997.

• 1998 and 2005 were the warmest years on record.

• The planet’s average surface temperature has heated up a little more than 1 degree Fahrenheit over the past century, “which doesn’t sound like a lot, but in fact, it matters,” Gutzler said.

“We’re really very confident that the climate is really changing, it’s warming up, and the only way to explain it is by greenhouse gases.” Solar fluctuations and volcanic emissions can’t account for the steady upward trend.

As a result, utility companies are already changing their rates to reflect warmer winters and hotter summers. “These warming trends, as modest as they are, are already affecting your life,” Gutzler said. “There is nothing phony, fictitous, or hypothetical about it.

“Global warming is nearly global, every year.”

Of course, temperatures do go up and down, and there will be cooler years within the warming trend. 2008 was one of them, he said.

Tree-ring and other historic data show that, for the past 1,500 years or so, the earth’s temperature has gone up and down and up and down, but has varied by just a couple 10ths of a degree. So a rise of 1 degree is a lot, he said. “It doesn’t prove why it’s happening, but it tells us it’s changing at a rapid rate compared to the last couple millennia.”

Computer modeling indicates humans are the cause of this recent, more rapid temperature increase.

Computer models aren’t perfect, but they are pretty good, according to Gutzler. If you start with the climate that existed at the beginning of the 20th Century and run the models forward, they pretty accurately predict what actually did occur in the 20th Century.

“You get the right answer for the period of time when we know the answer.”

However, if you run the models without factoring in human-caused aerosol pollution and greenhouse-gas emissions, the models predict little variation in temperature, “completely missing the warming at the end of the 20th Century.” When you do add in the human factors, the models predict what did indeed occur.

What those same models show for the 21st Century “depends on what greenhouse gases will be,” Gutzler said.

The most abundant greenhouse gases on Earth are water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and ozone, in that order.

Computers predict different weather outcomes depending on how much of the greenhouse gases — in particular, carbon dioxide — are put into the equation. “We don’t really know what the CO2 levels will be, because it depends on the choices people make.”

Assuming a “middle” approach, with a less-ambitious policy of curtailing CO2 emissions, it’s projected that northern New Mexico (an area very similar to Southwest Colorado) will see an average increase of 5 degrees Fahrenheit in winter and 7 degrees in summer. And although some years will be colder than others, the trend will be steadily upward.

“By 2050, the coldest summer we see is still hotter than we have ever experienced,” Gutzler warned. “By 2100 the coldest summer is hotter than humans have ever experienced in their history.”

Overall precipitation will not change so much, but there will be a propensity for greater fluctuations. Already, in the past 15 years, northern New Mexico has experienced its driest and wettest winter and summer in recorded history, Gutzler said.

In addition, “the wet places on earth will get wetter and the dry places will get dryer” in the future, he said.

“If you happen to live in one of these places where it’s dry already, then you’ve got a problem.”

Of course, droughts are not new, Gutzler acknowledged, “and you can’t blame people for the fact we have had many over the past millennium.”

Meteorologists are beginning to think that ocean temperatures and currents play a much bigger role in droughts than was previously understood.

When the Atlantic is warm, the United States seems to get less precipitation. And it’s only recently been learned that when the Atlantic is warm and the Pacific is cold at the same time, “there seems to be not much precipitation in the Southwest,” Gutzler said.

That was the situation in the 1950s, when the Southwest experienced one of its worst droughts in the past century.

If climate change continues and the warm-Atlantic-cold-Pacific situation occurs again, the drought will be worse, he said. If the 1950s drought is replayed in 2050, when overall temperatures are higher, “it has big consequences for water resources.”

Again, the problem is not that less precipitation will be falling overall, but that warmer temperatures will affect when and how that precipitation comes down.

Warmer winter temperatures “clobber the snowpack,” he said. Less precipitation falls as snow; what snowpack there is melts earlier, to the dismay of ski-area managers. At some point, cloud-seeding won’t even help, because “the snow won’t stick around.”

“Snow may be non-existent south of the Sangre de Criso range in New Mexico by the end of the 21st Century.”

In the warm future, spring runoff occurs earlier and rivers dry up sooner, Gutzler said.

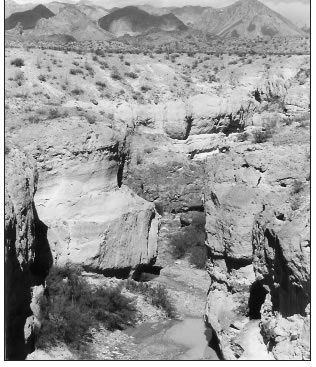

Will Southwest Colorado look like Big Bend, Texas (shown here) in coming decades? It’s possible, a drought expert warns. Photo by Gail Binkly

Projections for the Rio Grande River show a huge drop in flows in May and June in future years, “because the snow has already melted and flowed downriver.”

The ground will dry out faster because of warmer temperatures, so less vegetation grows, particularly in southern regions. Higher temperatures promote more evaporation, “and water wafts away to undeserving places like Kansas and the East Coast,” Gutzler said, smiling.

Not preparing for these changes would be “unbelievably arrogant and stupid,” he said.

“I don’t particularly want Southwest Colorado to look like Big Bend [Texas], but the climate is trying to push us in that direction.”

Gutzler said the primary source of carbon dioxide is burning fossil fuels, and the biggest and fastest-growing source of those is coal.

“Sooner or later we will need to reduce emissions from fossil fuels,” he said. “We may be burning less oil anyway, because there will be less oil to burn, but there’s plenty of coal, so we’d better be developing sequestration techniques for those emissions.” Gutzler’s talk was followed by a lively question-and-answer session. Asked whether people would “boil” in the Four Corners, he said no.

“There are places south of us that are 5 to 7 degrees warmer and people there don’t boil. . . but our civilization is fairly well tuned to a stable climate. If the climate of Michigan starts to look like New Mexico in a century, that’s a problem.”

Another questioner asked whether it wasn’t preferable to have a warming trend than a cooling trend. Gutzler agreed.

Orbital fluctations are believed to be the cause of periodic ice ages, he said, and there is one hypothesis that if people had not pumped so much greenhouse gas into the atmosphere so far, we would already be in the very early stages of another ice age. However, real cooling wouldn’t happen for a millennium or so, whereas warming is occurring much faster.

“Five degrees warmer is better than a kilometer of ice,” Gutzler agreed, “but it’s going to take a long time to form that kilometer of ice.”

Mike Preston, manager of the Dolores Water Conservancy District, asked about water-management recommendations. Gutzler said anything that minimizes downstream storage and maximizes it at higher elevations would be good. “Make it legal and feasible to store water upriver,” he said.

‘It’s really nice to come out to a cultural event like this and leave my troubles behind,” Preston commented, to general laughter.