It’s spring, and the sun-dappled waters of the Lower Dolores River are warming. In a stretch downstream from the Dove Creek pumping station, thousands of fish eggs are waiting to hatch. They’re flannelmouth-sucker eggs – laid and fertilized by a few old fishes that have survived more than 25 years.

But lurking in the river are smallmouth bass, and they’re hungry. Nosing along the gravel riverbed, they spot the eggs and begin eating.

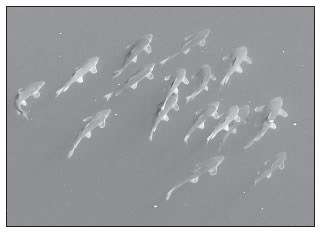

Native flannelmouth suckers get ready to spawn on the Lower Dolores in 2006. Photo by David Graf

When they’re done, just a few eggs remain. A week later, when those larval fish hatch and begin to float into the stream, the bass aren’t far away. In a flash, the remaining larvae have been devoured.

This is the sort of primal drama that occurs all the time in nature, and is rarely of much concern to human beings.

But a lot of folks are taking a keen interest these days in the doings of fish on the Lower Dolores. They are particularly interested in three warmwater native species – the flannelmouth sucker, bluehead sucker and roundtail chub. And some of the people most concerned about these fish aren’t biologists or environmentalists, but local water managers and irrigators.

That concern has led to the formation of an unusual alliance including rafters, anglers, environmentalists and water-users with the shared goal of helping the native species survive.

‘A looming issue’

For Amber Kelley, Southern Dolores river organizer with the non-profit San Juan Citizens Alliance, the presence of native fish is key to a healthy river environment.

“The native fish are a really important component of the whole ecosystem down there,” she said. “They have their own intrinsic value as a species, but also they are, hopefully, part of a healthy ecosystem.”

For others, however, aiding the fish could have some very practical benefits to humans.

That’s because of the possibility that one or more of those native fish might someday make it onto the federal endangered-species list. If that should happen, the Lower Dolores could potentially be included in critical habitat for the species, and some of the water now used for growing crops and slaking the thirst of municipalities could be diverted to save the fish.

“The main reason [to help the fish] is to make sure we don’t have a listing and create a situation where part of that [Dolores] project water will have to be used to re-establish the population of those native fish,” Montezuma County Commissioner Gerald Koppenhafer told the Free Press. “That would basically take away from the livelihood of people using the water.

“As a commissioner, I can’t do my due diligence and look out for this county without trying to take care of this situation.”

His concern is echoed by others in water- management and local government. “There is a looming issue there,” agreed Don Magnuson, general manager of Montezuma Valley Irrigation Company, a private water company. “[A listing] can make life difficult for water managers.”

“We all have different reasons we want to help the fish,” said Dolores County Commissioner Ernie Williams. “It would be very detrimental to Dolores County if they list those fish and start taking the water to protect them. That’s one of my concerns.”

“Dealing with the native species is a water-supply protection issue,” said Mike Preston, general manager of the Dolores Water Conservancy District, which manages McPhee Reservoir and provides water to the area. “We’re committed to the ecological goal as well, but the water supply is our broad, primary interest.”

Williams, Magnuson, Kelley, Koppenhafer, and Preston are members of the Lower Dolores Working Group, formed in December 2008, as well as a sub-committee of that group that is working on a possible legislative proposal to create a special management area along the river.

Dwindling numbers

In the early 1980s, the Dolores was one of the longest undammed rivers in the Lower 48 states. McPhee Dam, completed in 1986, was a tremendous boon to agriculture and residential growth in the area, but, like all dams, it had environmental consequences. It divided the lower portions of the river from upstream tributaries where some native fish lived. It also changed the amount, timing and temperature of water flows, and introduced some non-native, predatory fish into the river.

As a result of those and other factors, the numbers of flannelmouth suckers, bluehead suckers and roundtail chubs in the Lower Dolores are at epic lows.

Recently, the legislative sub-committee of the Lower Dolores Working Group heard from three native-fish specialists with whom it had contracted to conduct a review of existing science about the fish.

The experts painted a gloomy picture of the three species’ status, saying they were all in danger of disappearing from the Lower Dolores entirely.

That wasn’t news to biologists with the Colorado Division of Wildlife.

“They have been declining for some time,” Jim White, a DOW aquatic biologist based in Durango, told the Free Press. “Ever since water development in the 1880s, their habitat has been under stress.”

The three species are in trouble not just on the Dolores but throughout the Colorado River Basin, where they have disappeared from about half their historic habitat. A range-wide conservation agreement involving the Four Corners states plus Wyoming and Nevada is in place.

But the fish are having a particularly rough time on the Lower Dolores, especially the 100 miles from the dam to the confluence with the San Miguel River. That stretch has one of the poorest native-fish populations of large Western rivers, according to the DOW, and the species’ range has shrunk considerably. Native suckers are nearly gone from 53 miles of the Dolores above Disappointment Creek where they once were common.

Furthermore, the native fish remaining seem to be disproportionately old, possibly dating from the relatively flush water period after the dam was built but before all the allocated water was being taken.

“They are [in bad shape],” White said. “It depends on where you are in that river system. Below the San Miguel, the native-fish status is better. There is evidence of reproduction and higher numbers of fish but not really what the system used to support, prewater development.”

So there is general agreement that the native fish are in decline and need help. But the causes for the decline are numerous and complex, and thus the solutions are elusive. And no matter what solution is suggested, there is a down side.

Temperature changes

One of the major factors believed to be harming the fish is a change in the way water comes down the Dolores in spring.

Before the dam, the river stayed fairly cold well into spring, as snowmelt came down from the mountains. There would be a high peak of runoff around in late May and then the river would slowly get warmer and drier.

The dam changed all that. Now, in a typical, moderate-flow year, the water below the dam warms up early. That’s because McPhee’s managers are holding it back in order to fill the reservoir and also, ideally, to prepare for a spill (the technical term is a managed release) for boaters around Memorial Day. Until the spill, flows below the dam are scant and thus the water warms faster than normal.

“With McPhee, you had several impacts to the spring runoff pattern,” White said. “Although there are more predictable base flows than there used to be given the size of the channel, the habitat is quite altered.”

Temperature cues native fish to spawn, so when the water warms up early, they spawn early. Then the sudden gush of cold water from the reservoir sends them into “thermal shock,” causing young larvae to die.

The solution is simple, in one sense: Recreate a more-natural set of temperature changes. The problem is how.

One way would be to spill more water earlier in spring, to prevent the unnatural early warming. There are two problems with that.

First, the reservoir’s managers must make sure there is enough water in the lake to fulfill all the allocations later in the summer.

Second, spilling earlier means an earlier, colder rafting season. Managing for rafting is a legal obligation under the documents that created the reservoir.

Yet another way to prevent the “thermal shock” of the sudden cold spill would be to release water from higher in the lake. The dam was built with selective level outlet works, called SLOWs, so that water could be released from different reservoir elevations.

Throughout McPhee’s history, however, water has been released only from near or at the bottom of the dam, where it is very cold and devoid of life.

It would seem like a no-brainer to release warmer, higher-elevation water instead – but, again, there is a catch: It would let nonnative fish into the river.

McPhee has been stocked with game fish, including the highly predatory smallmouth bass. Some bass already are present in the Lower Dolores, thanks to a genuine spill (meaning, over the causeway) that occurred in 1993. Because of some not-completelyunderstood limiting factors, however, they seem mostly confined to the reach between the Dove Creek pump station and Disappointment Creek downstream.

Biologists say it could prove disastrous if the bass spread. In systems such as the Yampa River they have exploded, overwhelming native species. And there seems to be no foolproof way to keep non-native fish and their eggs from slipping through the higher SLOWs.

Another fish that worries managers is the white sucker, which will interbreed with native suckers, essentially wiping them out. The white sucker is largely absent from the Lower Dolores, and managers want to keep it that way.

For those reasons, releasing water from the upper levels of the lake is not a possibility at present.

Trouble with trout?

Then there is the problem, if it is a problem, of the catchand- release trout fishery – browns, cutthroats and rainbows – below the dam downstream to about Bradfield Bridge. The fishery, like the commitment to rafting, is a legal obligation created with the establishment of the dam.

Some people believe the trout are detrimental to native fish because browns, which are very hardy and self-sustaining, will eat native species. In addition, the trout may compete with the suckers and chub for food and habitat.

But Division of Wildlife biologists say the picture is not so black-and-white. Both trout and native species have tended to do well or poorly in relation to the amount of water in the river, they say. This indicates they occupy somewhat-different niches.

In addition, biologists note, trout prefer the cold water that exists just below the dam – something that isn’t likely to change any time soon. They won’t move further downstream because the water is too warm.

Preston said he is convinced of that after hearing from the native-fish researchers. “For the foreseeable future the first eight miles [below the dam], at least, will be cold, so there are no reasons in my mind to stop stocking rainbows, because the water there is too cold for natives,” Preston said.

Six-lane freeway

Then there is the factor that may be the stickiest: the amount of water in the river year-round, known as base flows. Biologists are united in their belief that more water would help the fish. True, the native species are hardy and evolved in a system that historically used to dry up in the hottest summer months, while today there is water in the river year-round.

But biologists say the amount just isn’t enough. For one thing, the spring spill is never as large as it used to be before the dam, which limits the high flows needed to scour out deep pools where the fish could wait out dry periods.

“You get a lot of folks that say, ‘The channel’s wet now – it dried up all the time before’,” White said.

The difference is that the historic river channel was broad because of the occasional huge spring floods. Now the year-round trickle isn’t enough to remove sand, much less rocks. “Now it’s like a six-lane freeway with only one lane of traffic going down it,” White said. “Yeah, there’s water in the channel – it looks better than it did when it was dried up – but these habitats are so degraded.”

The problem is, of course, where to find additional water in a fully allocated system.

Earlier this year, the Montezuma Valley Irrigation Company board floated an idea that raised hopes of improving the status of native fish. The proposal was to lease 6,000 acre-feet of the company’s surplus water to the state of Colorado for its instream-flow program. The program acquires water from willing sellers or lessors for the benefit of the ecosystem in streams and lakes.

MVIC’s board proposed leasing the water for just three out of 10 years — which years would depend on stream-flow conditions.

“No matter how you look at the situation it seems like there’s additional water needed, so we felt we had the ability to supply some of that water,” Magnuson said, adding that his opinion is not that of many stockholders. “The lease would give us the ability to really test what the [biological] impacts were, in a temporary situation.”

But when the board put the proposal to MVIC’s stockholders in May of this year, they voted it down, concerned about giving up any water in the arid Montezuma Valley.

Magnuson said the lease idea may return in some form because it generated considerable interest. “You can’t go any place today without people talking about it.”

Another idea to put more water down stream is building another small reservoir. The DWCD holds a water right on the Upper Dolores that could allow it to build a 20,000 acre-foot reservoir on a tributary. It would be filled during spring runoff. “Then when you need that water, it’s sitting in that reservoir,” Preston said.

But building a dam would be expensive, not to mention controversial.

A sense of hope

The problems seem daunting, but momentum is building to take concrete steps to try to aid the fish.

The Lower Dolores Working Group was created because the BLM, which manages much of the landscape through which the Lower Dolores meanders, had listed the river as “preliminarily suitable” for designation as a federal Wild and Scenic River.

That designation – which would require an act of Congress – would bring with it a federal reserved water right along with a variety of federal regulations, and few locals wanted to see that. So the group was formed to come up with alternative ways to protect the river.

The LDWG’s sub-committee is working on a proposal for legislation for a special management area on the Lower Dolores, trying to work through the tangle of issues around the native fish while respecting private water rights.

After hearing from the native-fish specialists, committee members seem energized and hopeful. The researchers discussed a number of ways to help the situation even within the constraints involved.

“I very much appreciated the information that came out of the scientific studies,” said Magnuson. “From my personal perspective, these environmental issues below McPhee Dam are a community problem. If the community wants to do things to improve the situation, I think we have opportunities.”

Koppenhafer agreed. “I think it’s a very complicated problem and it’s going to take some give and take on all sides, but we can make good things work.”

Managers at the Bureau of Reclamation and DWCD, who operate the dam, already have experimented with releasing more water early in spring to provide more-natural temperatures. And the rafting community has expressed a willingness to give up a little boating water to help the native species.

One good thing about the native fish is that, because they live so long, they don’t have to have successful reproduction every year. “It just has to happen often enough to sustain the population,” White said. “They just need a good year every four or five years or so.

“Nobody in the biological community is thinking we can go back to pre-water development populations of fish, but we’d like to see a more stable population with evidence of reproduction and multiple age classes.”

Kelley said the committee has “really come together” in a way that gives her hope.

“I’ve been so impressed by how well we’ve all been able to work together in the working group and legislative sub-committee. Seeing the agricultural community and conservation community and recreation community and local governments come together to work on a solution – I think that’s a positive, positive thing.”