One June day in 1912, gunfire rattled Ophir, Colo. When the roar subsided, “twenty-five-year-old Charles Turner lay in the dirt by the railroad tracks, blood pouring from his mouth, and a hole in his chest.”

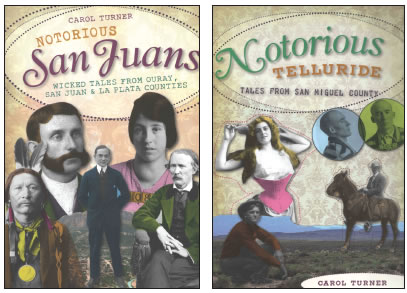

Ninety-eight years later, his grand-niece, Carol Turner, published his story, which she called “Death by Gold Fever,” in her book “Notorious Telluride: Tales from San Miguel County,” published by the History Press.

“I am interested in all those wonderful, exciting, juicy stories from the past,“ the Denver-area writer laughs.

“I am interested in all those wonderful, exciting, juicy stories from the past,“ the Denver-area writer laughs.

With a bachelor’s degree in English from Sonoma University, and a master’s degree in creative writing and literature from Bennington College, she considers herself a writer, not a historian, who got “sucked into writing about the past” by Charlie’s story.

He came from Montreal to Denver with his family in 1885 at age 5. His father died, leaving Charlie’s mother, Agnes, alone with several children.

“Death by Gold Fever” describes her struggle to raise them with income from property in Montreal, wages earned by her older boys, and help from her brothers, who mined on Yellow Mountain in Telluride.

Eventually, the Yellow Mountain property passed to Agnes and one brother, who worked it with a partner, Frank Ensign. By the time Charlie grew up, Ensign controlled the entire holding.

As far as Carol Turner knows, Ensign had a good reputation, and came by the land honestly. But Charlie believed the family “had been ripped off ” and though unarmed, attacked Ensign, who shot him with a 32-caliber rifle.

Turner decided to learn why Charlie started the altercation. Newspapers in Telluride told her nothing. One called him a bully; another reported him to be a nice person. Turner believes Charlie’s reaction came from watching his mother mismanage the family money. For Turner, Charlie’s story shows that “life was rough and cheap” on the frontier.

As she researched Charlie, she came across tales from Ouray, Durango, Silverton, and Pagosa Springs, in the Colorado Historic Newspaper Database, as well as her own memory. Her mining-engineer father had searched for the old Catbird Mine in Telluride, and worked the Eureka Mine in Boulder Canyon.

“I grew up [in Boulder] right around the corner from riches,” she laughs.

The History Press limited her to 35,000 words per book, so when “Notorious Telluride” reached the limit, she wrote “Notorious San Juans: Wicked Tales from Ouray, San Juan and La Plata Counties.”

Her favorite story in this collection, “Death of the Secret Service Man,” occurred in 1907 when the Secret Service’s main job entailed catching counterfeiters.

However, agents had also begun investigating fraudulent homestead claims. Because the government limited where mining companies could purchase property, and charged for mineral rights, speculators bought land from farmers, evading fees and restrictions.

So on Sunday, Nov. 3, 1907, while Secret Service agent Joseph Walker stood guard above ground, two government contractors and two Secret Service agents descended by rope into an air shaft on a farm, and found themselves in the Hesperus Coal Mine near Durango, Colo. After exploration, they returned to the shaft to find their rope cut and brush blocking their escape. Shouts for help to Walker brought no response.

One of the contractors scrambled up the rock and reattached the rope. When everyone climbed out of the hole, they found Walker sprawled on his back, riddled with bullet holes.

Secret Service men from Washington, D.C., and Denver poured into Durango. Police arrested two men who claimed they had shot Walker in self-defense. They went to trial.

“I won’t tell you what happened,” laughs Turner. “But I can tell you it had far-reaching implications.”

Those included the founding of the FBI and (because Joseph Walker’s widow had no death benefits) the establishment of a pension for Secret Service wives.

“It was a pretty wild history, and justice was hit-ormiss,” Turner muses. Defendants often had stronger cases than the prosecution. Short prison sentences resulted in citizen mobs lynching crooks. People operated on both sides of the law, trying to survive.

Turner did most of the research for “Notorious Telluride” and “Notorious San Juans” on the internet. Piecing her stories together from her sources, she found as much misinformation as accurate accounts. She acknowledged the disparities by pointing out places where the tales got murky, or where newspaper articles disagreed. “I found stories where the newspaper reporters obviously just made something up. There’s a story like that in my Telluride book.”

The tale describes a stagecoach robbery. Right after the incident, the papers reported that a bandit shaking with fright had stopped a slow-moving stage. Fearful that the man’s guns would go off accidentally and kill someone, the half-dozen male passengers gave him some odds and ends and sent him shuddering away.

A year later, in a second version of the story, the bandit, a gun in each hand, stopped a stage coming full speed down a hill by grabbing the bridle of one of the lead horses. Women passengers screamed in terror.

“I would like to have seen that,” Turner laughs. “The newspaper reporters were as wild as the [desperadoes].”

Besides “NotoriousTelluride” and “Notorious San Juans,” Turner has written “Notorious Jefferson County: Frontier Mayhem and Murder,” and “The Forgotten Heroes and Villains of Sand Creek,” published by the History Press.

“I consider myself like my father, who was gold-mining. I’m tidbit-mining. It’s wonderful. So much fun.”