Colorado’s wolverine population has grown recently. It’s up to a total of one.

In 2009, a male wolverine trapped and collared in the Grand Tetons of Wyoming journeyed 500 miles to Colorado and took up residence in the high peaks around Rocky Mountain National Park, where he remains.

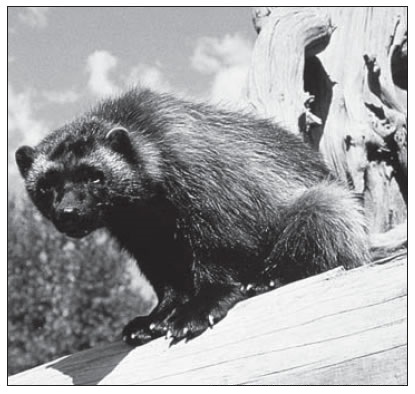

A wolverine sits near an interstate in Washington state. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recently decided the animal, which is the rarest carnivore in North America, is “warranted but precluded” for listing and protection under the Endangered Species Act. Photo by Jeffrey Lewis/U.S. Department of Transportation

It was the first confirmed sighting of a wolverine in the state since 1919.

That could change, however. In July 2010, the Colorado Wildlife Commission approved a request by the state Division of Wildlife to begin discussions with stakeholders about a possible wolverine reintroduction. Though still in very preliminary stages, the idea gained impetus in December, when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced that it was adding the animal to its list of candidates for endangered-species status.

The population of wolverines in the contiguous United States was found to be “warranted but precluded” for protection under the Endangered Species Act. That means that while the agency deemed the population to be in need of protection, rule-making on behalf of the wolverine is precluded by the need to take measures for other, higher-priority species. Candidate species do not receive protection under the ESA.

That status will be reviewed annually.

In the meantime, Colorado is moving ahead with discussions about what a reintroduction might entail and what its effects might be.

Opening the dialogue

“We have had stakeholder meetings to present the idea,” said Eric Odell, DOW species-conservation coordinator, by phone from Fort Collins.

“We don’t have permission from the Colorado Wildlife Commission to go forward with the reintroduction, just to open the dialogue.”

Meetings have been held with agricultural interests, winter-recreation groups, nongovernmental organizations such as conservation non-profits, and other agencies. In addition, the DOW is working to develop a candidate conservation agreement between the federal land-management agencies, such as the Forest Service, and the Fish and Wildlife Service.

“We anticipate determining how federal land-management practices and the use of the federal lands would or would not be impacted by doing a restoration,” Odell said.

“One of the sideboards we’ve been using for the whole idea of this restoration is, we’re interested in doing it, but not at any extensive political, social or economic costs.”

The DOW had talked about a wolverine reintroduction at least a decade ago, when the Canada lynx was being brought back to Colorado. However, that effort raised such controversy, and took so many resources, that the DOW put the wolverine on the back burner.

This year, the agency announced that the lynx reintroduction was a success, with the felines reproducing faster than they are dying. More than 140 lynx have reportedly been born in the state since the animals were first released into the San Juan Mountains of Southwest Colorado in 1999.

Odell was not involved in the lynx reintroduction, but he said the agency “learned a lot from it – both technically and in regards to how to do it from a political standpoint as well.”

While the wolverine restoration might be similar to that of the lynx, it would differ in some ways, he said. “I don’t think we went to the same extent of getting stakeholder input as we are now,” Odell said. “We’re learning from our previous effort.”

He said so far, the feedback at the stakeholder meetings has been mixed.

“The ag groups are somewhat concerned with the potential impacts on grazing – not with direct take or predation [of livestock], because that’s not an issue. The non-governmental organizations are very enthusiastic. The backcountry recreation and ski industry – their concern is loss of access, area closures. What we are hoping to accomplish is minimizing or avoiding any kind of impact like that.”

No backcountry closures were involved in the lynx reintroduction that he knows of, he said.

‘Chasing the Phantom’

Wolverines have a reputation as vicious, even frenzied fighters – “the Tasmanian devil of America,” Odell said. “But they’re nothing like that.”

However, these large weasels (generally 25 to 40 pounds) are indeed opportunistic, powerful creatures that survive in a very challenging environment: cold, barren slopes of high peaks, tundra and boreal forests where snow is deep late into the spring. Food is scarce in such places, but the wolverine has adapted by learning to eat almost anything – from berries and insects to squirrels and marmots to the occasional deer trapped in deep snow. It will also eat carrion, even crunching up bones with its strong jaws.

Researchers say wolverines can smell a carcass buried in 20 feet of snow and will fearlessly challenge much-larger animals, even bears, over kills. They are wide-ranging and largely solitary, though new findings show that kits stay with their mother for up to a year and the father helps teach the kits how to find food.

There has been a surge of interest in the species recently. Last year, PBS aired “Wolverine: Chasing the Phantom,” film-maker Steve Kroschel’s account of his 25 years caring for injured and orphaned animals on a preserve in Alaska, where he became one of the few men in the world to raise wolverines in captivity. The documentary shows him romping and playing with two grown wolverines that he brought up.

And in the book “The Wolverine Way,” published in 2010, author Douglas Chadwick, a volunteer with the Glacier Wolverine Project, celebrates the animal’s wild spirit and tenacity.

The rarest carnivore in North America, Gulo gulo (Latin for “glutton”) was never abundant in the Lower 48 states, researchers say. Although Michigan is nicknamed “the Wolverine State,” the species was reportedly extirpated there 200 years ago, though some animals eventually moved back down from Canada. The only known wild wolverine in Michigan in modern times died of natural causes in March of last year.

Because the animal is so solitary and secretive, dwelling in extremely remote areas, it’s very difficult to establish its population. According to “Wolverine: Chasing the Phantom,” the worldwide population is estimated at 15,000 to 30,000, all in cold, northern latitudes, especially Canada. According to different sources, there are 200 to 250 wolverines in the Rocky Mountains in Idaho, Wyoming and western Montana, plus a few more in the Northern Cascades of Washington state.

The population living in the contiguous U.S. is considered a distinct population segment by the Fish and Wildlife Service, and that is the population that is a candidate for endangered-species listing.

Needing deep snow

In the past, wolverines were extirpated from the Lower 48 primarily by humans, who trapped them for fur and also poisoned them because they raided trap lines. Today, the greatest threat to the species is climate change, which could reduce the snow upon which the animal depends.

It’s especially adapted for surviving in snow, with feet that act almost as snowshoes, and females make their dens 15 feet deep or so in snowpack in February.

“Research coming from the Rocky Mountain Research Station in Montana shows that one of the most indicative features of wolverine habitat is areas that retain deep spring snowpack,” said Odell. “Those areas are used for dens. That’s part of the reason behind the Fish and Wildlife Service decision that it was warranted but precluded – the research indicates climate change was a big issue.”

Computer modeling of future climate change indicates Colorado’s high mountains might remain good wolverine habitat in coming decades.

“Some of the models are showing that places at higher latitudes but lower elevations may lose snowpack, and Colorado may have some of the best wolverine habitat,” he said.

“That’s part of the idea of the restoration effort, addressing climate change, which the Endangered Species Act doesn’t have a good way to do. This may be a way for the Division of Wildlife to address one of the primary threats to the species.”

Wolverines were likely native to the state, he said, though it’s difficult to come up with hard evidence. “In the early 1900s, people didn’t keep track of the distribution of species the way we do now. We certainly expect that they were here, though they were never high-density animals.”

Wolverines “were extirpated from the Sierra Nevada and southern Rocky Mountains” in historic times, according to a fact sheet from the Fish and Wildlife Service. Colorado’s carrying capacity for the species is probably about 100, according to information from the DOW.

No threat

Odell said, despite the wolverine’s feisty reputation, it poses no threat to humans. “There is no need for people to be concerned about being attacked by a wolverine. They are very solitary, not like wolves in a pack.”

Ag producers should have little to worry about as well, he said, because wolverines’ diet consists largely of small mammals and carrion. “They may rarely kill or depredate on young ungulates. It’s happened on a handful of occasions.”

One big issue will be whether the presence of wolverines requires restrictions on winter recreation in remote areas. Snowmobiles and cross-country skiers can disturb denning females, causing them to move their young.

At this point, the DOW will move ahead with continued dialogue, Odell said, repeating that a restoration effort has not been approved.

“We will continue to meet with stakeholders to see if we can come to some agreements,” he said, “so we can go forward with a restoration while not causing tremendous political or economic impacts to the users of the state.”