Dealing a blow to the Cameron Chapter’s plans for economic development, the Navajo Nation central government and Navajo Tribal Utility Authority (NTUA) recently announced plans to break ground late this year on an 85-megawatt wind farm 80 miles west of Flagstaff, Ariz., on the Big Boquillas Ranch.

Touted in the Dec. 24, 2009, press release as the United States’ first large-scale wind project to have majority ownership by a Native American tribe, “Big Bo” was also described as the first large-scale wind project in the Navajo Nation.

Members of the Cameron(Ariz.) Chapter of the Navajo Nation listen Dec. 15 as officials with IPP and Sempra deliver bad news about the prospects for a much-hoped-for wind farm that would bring badly needed revenues to Cameron. Photo by Sonja Horoshko

“This is historic,” said Walter Haase, NTUA general manager in the press release. “For the first time, the Navajo Nation is a majority owner of an energy project that will introduce a new economy to the Navajo Nation for the benefit of the Navajo people.”

But chapter officials at Cameron, Ariz., a small, impoverished community in the Navajo Nation near Tuba City, do not see the project that way.

Cameron Chapter has been working to develop a 500-megawatt, $1 billion wind farm on nearby Gray Mountain. [Free Press, December 2008, February 2009 and April 2009]. The Big Bo farm could take up capacity on transmission lines that Cameron was hoping to use.

The Cameron effort “has been in process over three years,” explained Chapter President Ed Singer. “It’s the largest and the first on Navajo land. We’re ready — we’ve been ready for two years. It’s only [Navajo] central government, the RETF (Renewable Energy Task Force) and NTUA that have not responded to our request for a business-site lease.

“Instead, they hijacked our time frame with delays that risk keeping us off the transmission lines while they fasttracked the Big Bo project, which means Big Bo did not have to go through the process as they asked us to do.”

The transmission lines crossing the Cameron community are critical to the project’s feasibility. Three years ago the chapter chose International Piping Products to develop a wind farm on Gray Mountain as a local community initiative, giving the Texas-based company authority to conduct a feasibility study. IPP then stepped up into the queue on the transmission lines that could carry the power for sale in Nevada and California.

Since then the company has spent nearly $3 million to measure the wind and cover the hard costs associated with anemometer construction, data collection, environmental and archaeological studies, and requirements by federal, state and local as well as Navajo agencies. Data now confirms that the site is possibly the most consistent Class 4 (on a 1-10 scale, with 10 the best) wind source in Arizona.

Indicators of that quality make it possible to partner with large, experienced energy companies capable of building a wind farm of that size. Sempra Energy, a California company with a renewable-energy track record, joined IPP and the Cameron Chapter in the effort to build the wind farm.

The chapter voted to award Sempra the business-site lease required to break ground. A request for approval of this step was delivered to the tribe’s central government in Window Rock, and thus began a race to reap control of the wind.

“Their [the Navajo government’s] job is to review the requirements and approve the request; sign off so we can get on with our project. It is not their job to change ownership of the project, replace it with something else or another company, or do business with our work,” said Singer.

Arvin Trujillo, director of the Navajo Division of Natural Resources, conducts a Renewable Energy Task Force intake meeting with Cameron Chapter representatives on Jan. 15 in Flagstaff, Ariz. Photo by Sonja Horoshko

Instead, the Division of Natural Resources, headed by Director Arvin Trujillo, responded in March 2009 by calling for a 12-week moratorium on all renewable-energy projects, citing a need for the Navajo Nation to develop a renewable-energy policy and appoint an energy task force by the beginning of summer.

According to Singer, “the project was hijacked long before, back in December 2008, when the Economic Development Committee and the Resources Committee met to decide who had the authority over energy development. At that time they decided we should work with the Division of Natural Resources even though they did not have an energy policy.”

Twelve weeks passed with no energy- policy decisions and no task force in place.

Cameron Chapter, Sempra and IPP began hearing rumors that the Division of Natural Resources was expanding the role of NTUA to include renewable- energy development. NTUA, a Navajo enterprise inexperienced in building renewable-energy projects of this scale, was now poised to assume command as the lead agency for Navajo energy projects.

President Joe Shirley, Jr., agreed to a meeting on Aug. 3 with the Cameron Chapter. It opened with a helicopter tour over the Gray Mountain site. Later, Arvin Trujillo and Louis Denetsosie, tribal attorney general, joined the group in a roundtable discussion in the presence of the community with Jim Sahagian, Sempra project manager, and the Window Rock entourage.

“I will do everything I can to help out,” Shirley told Sahagian. “I appreciate all the work you’ve done this far here at Gray Mountain. We are here working together… legislative and judicial. But we need expertise, we need NTUA. I want you to get together and talk [with NTUA] right after this meeting.”

This was the first official announcement of NTUA’s presence in the project.

Sahagian replied, “We are different from other companies. We want to work in close partnership with the local chapter, we have worked with Cameron and we can do the project. It sounds like you are committed to move the project ahead. Can we look to your office for support?”

Shirley reassured Sahagian, “Whenever you come to an impasse you can come to my office.”

But by late summer, when negotiations between NTUA and Sempra/IPP stalled, Shirley was unavailable. He was embroiled in his own campaign to hold a special election in December reforming the government. Two initiatives were scheduled for a vote of the people. The first would reduce the number of council delegates representing the local chapters from 88 to 24. The second would grant the president line-item veto power on portions of the council spending measures.

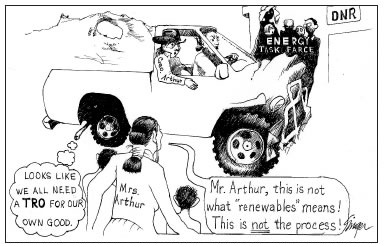

The controversy over a wind farm on the Navajo reservation in Cameron, Ariz., has grown heated. Ed Singer, president of the Cameron Chapter of the Navajo Nation, drew this cartoon recently as a commentary on the dispute.

Shirley’s focus was elsewhere while Gray Mountain wind-farm negotiations floundered and time began to run out on the transmission lines’ availability.

NTUA wanted 51 percent equity in the project. Sempra offered 20 percent ownership to the Navajo Nation with the possibility of more buy-in as the first 12 months of the project proceeded. But NTUA held fast, saying that it was the directive of the council that all business done with the nation must now be done with 51 percent ownership by the tribe.

Turmoil erupted in October when the Navajo Nation council voted to place Shirley on leave pending investigation into alleged illegal preferential treatment of two corporations operating on the reservation.

As the reservation’s residents focused on the election and Shirley’s appeals for reinstatement, no one had time to listen to the people in Cameron, or respond to the term sheet proposed by Sempra.

Time flies

Months passed without progress on the wind farm.

On Dec. 15, the Cameron chapter house glittered with tinsel and a lighted Christmas tree near the dais. Sides of beef roasted in the chapter kitchen ovens. A few elders arrived two hours early to socialize while officials set up tables and chairs for a banquet after the meeting. The Christmas meeting was about to begin without presents under the tree — no reply from NTUA, Window Rock, the energy task force or DNR; no movement on the economic opportunity that the wind farm represented for the Cameron people.

Sempra representative Mark Haarer and IPP Vice President Bruce McAlvain arrived with pumpkin pies and baskets of fruit, then surprised officials by requesting time on the agenda. They informed the people of Cameron that in this state of delay the project could not be further funded.

“IPP has invested $3 million in this project so far,” said McAlvain. “I have put over 100,000 miles on my truck going to meetings in Window Rock, Phoenix, Las Vegas and Flagstaff to make this project work for us all. And even though my family is here in Cameron, I have to think first about the well-being of my business and my family first. I cannot do more.

“After all the delays we have experienced, 13 new renewable-energy projects surrounding the area are moving forward. We are losing our place on the transmission lines. Even though they are smaller projects, collectively they are impacting the feasibility of doing the wind farm on Gray Mountain,” McAlvain said.

The formidable elder grandmothers took the microphone. They talked about central government letting them down, how they are being ignored, how the plans they had for their grandchildren are gone if this project isn’t built; how the forgotten people in their community are drinking yellow water seeping from the uranium sites in their backyards.

Nine days later, the news broke that Big Bo Wind was a go.

No people at Big Bo

What wasn’t stated in the press release was that no people live on Big Bo; it is fee-simple grazing land traded in a deal with then-Navajo Nation President Peter MacDonald in 1989. “Bo-Gate” unraveled his presidency as revelations of fraudulent procurement in the Big Boquillas Ranch purchase came to light.

Big Bo is a chapter in Navajo political history. It is not a chapter in the Navajo reservation.

“No community will directly benefit from development of its marginal natural resources,” said Singer.

A critical point in the negotiations surrounding Gray Mountain is how much income will flow directly to the chapter. Cameron developed the local community initiative and is now exercising rights to 1 percent of the revenue from the single-phase project, projected at close to $1.2 million a year, with the potential to grow as power prices increase.

Sempra is offering 4 percent of the gross off the top, said McAlvain, “meaning the community and nation get paid before any other bill is paid or even if the project loses money. Cameron Chapter will get 1 percent, the nation 3 percent, of that amount.”

During the last quarter of 2009, Sempra learned that the Division of Natural Resources, NTUA and the Shirley administration want the entire 4 percent of gross revenues to go to the central government and then trickle down to communities throughout the reservation, rather than to Cameron.

Respecting that Cameron Chapter was dealing directly with them as a business partner, Sempra/ IPP offered 1.5 percent for the chapter. When NTUA countered with one-half percent, Sempra/IPP went back with a request for a full 1 percent straight to the chapter as called for in the November term sheet and 3 percent for the central government, with a 20 percent equity in the project.

The proposal drew no response from the Window Rock entities. Meanwhile, the nation was in an uproar over the upcoming election and the issues around Shirley’s administrative leave.

On the eve of the Dec. 17 special election, Shirley was reinstated by Window Rock District Judge Geraldine Benally, who ruled that the council had not properly reviewed the bill that placed Shirley on leave. The next day the voters passed the president’s initiatives — the line-item veto and council reduction.

A glimmer of hope opened the New Year when Arvin Trujillo finally called a meeting in Flagstaff on Jan. 15 to discuss the Gray Mountain wind farm with the Renewable Energy Task Force led by George Arthur, also chairman of the Natural Resources Committee, and four other members: Trujillo; DNR Director Louis Denetsosie; Steve Gunderson of Tallsalt Asset Management Investments, Scottsdale, Ariz.; and Bill McCabe, a petroleum engineer who worked for IPP during the initial feasibility stages of the wind project but was let go a year earlier.

Trujillo then directed that the meeting format be split: Cameron Chapter representatives would meet with the task force, then the task force would meet with Sempra /IPP. They would not all sit in the negotiations together.

Divide and disappear

Trujillo asked the Cameron leaders, “How do you see your role in this wind project?”

Chapter President Singer outlined the project, including the partnership with Sempra and IPP. “My community has passed resolutions in support of building our wind farm on our land. We want more than just lease rates. We want our fair share of the income to use for our own economic development.

“We agree that terms submitted by Sempra are fair to us. This is an economic opportunity that is fading because of the interference of central government, their unwillingness to respond to our requests. Time is of the essence. We are ready. We want Sempra to receive the business-site lease and get on with the project.”

Council Delegate Jack Colorado added, “We have worked with Sempra since 2007 and, yes, it is the type of company the people would like to work with. Central government doesn’t even begin to think about what the people are saying. . . The people are frustrated. They want to go forward. They want to be included.”

Gunderson explained that NTUA and the Renewable Energy Task Force have worked out “a Wall Street model for the Big Bo project” that can be used for all the nation’s renewable-energy projects.

The meeting closed inconclusively with Colorado asking the chairman to reconsider letting representatives from the Cameron community in the meeting with Sempra/IPP. His request was granted. The community stayed, but the press was excused from the room.

After 15 minutes the door opened and all left with a new term sheet in hand, prepared by the task force long before the meeting.

The new terms restated 51 percent ownership by the tribe, but a critical item was missing: a percentage for the Cameron community.

Cameron had been eliminated by its own government. If the project should proceed, the community that developed it will receive only what revenues the tribal government chooses to send them.

Singer, a court interpreter, told the Free Press of comments made in the meeting by Sempra cultural consultant Peterson Zah, former president of the Navajo Nation.

Zah told the task force, and specifically George Arthur, “I came on this project two years ago. This is the 43rd meeting for me. … It is like we are having trouble consummating a marriage – we can’t get the union done.

“This project is different from Big Bo, where there are no human inhabitants. Gray Mountain is different. People live out there. People are affected by this.

“The community has gone through a lot. They live without power, with power lines overhead. This is their land. They are just out of the Bennett Freeze [a moratorium on development imposed because of a land dispute with the Hopi Nation]. You, especially, the Resources Committee, should understand this. People are drinking uranium water…

“I ask myself, ‘Will I see this? Am I too old?’ Instead, you should be helping the community. Good luck,” and he nodded toward Arthur, “with Big Bo. Mr. Haase [NTUA’s manager] is rejoicing too soon.”

According to Singer, Sempra’s final term sheet still calls for 20 percent tribal equity in the project and for 1 percent of revenues for the Cameron chapter. A meeting has been scheduled Feb. 12 with representatives of central government, the Resources Committee and the Renewable Energy Task Force.