There are many authors whose virtuosity inspires me to be a better writer. There are but a few, however, whose talent is so prodigious, so dispiritingly outsized, as to make me want to throw up my hands and quit writing altogether.

Arundhati Roy is one of those few. Roy exploded onto the world literary scene with her debut novel The God of Small Things, a voluptuous coming-ofage saga that explores the legacies of colonialism, sexism, and governmental oppression in modern-day India. Small Things won the Booker Prize in 1997, has been translated into more than forty languages, and provided the platform from which Roy has since established herself as one of India’s most outspoken and controversial social critics – activities that had, alas, kept her from undertaking a second novel.

Until now.

Until now.

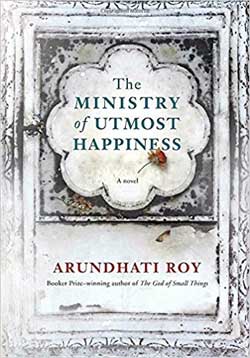

Twenty years after the publication of Small Things, Roy has reemerged from her self-imposed literary exile with her second novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. Like its predecessor, Utmost Happiness is awash in quirky characters, sly humor, cruel twists of fate, and an overarching sense of moral outrage. It is a Swiss watch of a novel whose intricate movements click and whirl, vibrate and chime, immersing the reader in the sights and sounds, the textures and smells of an India far removed from the saffron-suffused glam of Bollywood.

The novel centers on the lives of two very different women. Anjum Begum is a Hirja, a transsexual, living “with her patched together body and her partially realized dreams” in the walled city of Old Delhi. Then “on one of those windy afternoons when the prayer caps of the Faithful blew off their heads and the balloon-sellers’ balloons all slanted to one side,” Anjum finds an abandoned girl, weeping and terrified, on the steps of a local mosque. She adopts the girl, whom she names Zainab, and raises her in the sheltering nest of the Khwabgah, or communal home she shares with her fellow Hirjas.

Following the terrorist attack of 9/11, however, Anjum like all Muslims living in Hindu-dominated India finds her circumstances radically changed. While on a train trip to Gujarat she is caught up in a police sweep following a spasm of mob violence, and it’s not until months later that she is finally rescued, her head shaved, from the men’s section of a Muslim refugee camp. Traumatized by her ordeal, Anjum returns to Delhi but leaves the Khwabgah and takes up a squatter’s residence in an abandoned graveyard behind a hospital where she lives for the next 30 years.

While a student at Delhi University, S. Tilottama, aloof and beautiful, finds herself the object of three men’s affections. Musa, her soulmate, becomes a Kashmiri separatist leader after graduation. Naga, carefree and charismatic, becomes a noted Indian journalist. Biplab, a conservative Brahman, becomes Deputy Section Head of the National Intelligence Bureau. The four classmates’ lives reconnect many years later in the wartorn Kashmir Valley when Tilo, visiting the fugitive Musa, is arrested and taken to a dreaded interrogation center only to be rescued by Naga thanks to the intersession of Biplab.

Tilo’s and Anjum’s parallel stories eventually intersect, thanks to a quirk of fate best left to the reader’s discovery. By now Anjum has transformed her graveyard refuge into the Jannat Guest House, a ramshackle haven for misfits, Hijras, and Untouchables, and it is there that Anjum and Tilo finally make their peace with the world.

If the architecture of that fragmented narrative seems flimsy, that’s because it is. If you doubt its ability to hold both the reader’s fascination and the weight of Roy’s astonishing vision, then rest assured that you’re wrong. The Ministry of Utmost Happiness (Alfred A. Knopf) is a lush, nuanced, fantastic, and ultimately transformative reading experience that if not on par with its predecessor is nonetheless one of the best books you’ll read this year.

Chuck Greaves is a member of the National Book Critics Circle and the author of five novels, most recently Tom & Lucky (Bloomsbury). You can visit him at www.chuckgreaves.com.