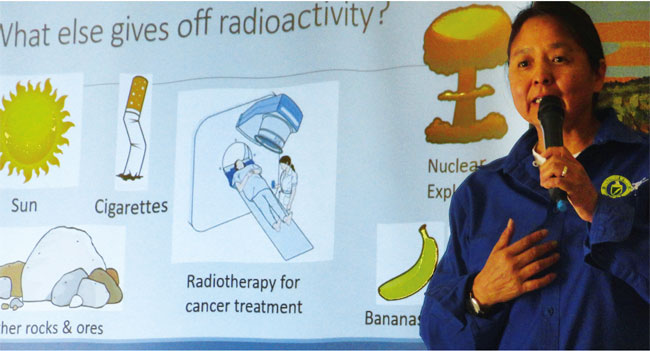

Angelita Denny, working in the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Legacy Management

was the lead scientist presenting Uranium 101, a facts-based education program presented

at Marian Lake Chapter. The workshop will be presented in Cove Chapter on July 10. Photo by Sonja Horoshko.

In January 2013, a group of federal agencies in consultation with the Navajo Nation completed a five-year effort to address uranium contamination in the Navajo Nation.

The effort focused on the most imminent risks to people living on the land. While that initial effort represented a significant start in addressing the legacy of uranium mining, much work remained and the same federal agencies – the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Department of Energy, Indian Health Service, and Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry – collaborated to issue a second five-year plan beginning in 2014. It built initiatives on the first plan and made adjustments based on information gained during that time, while addressing the most significant risks to human health and the environment.

Near the end of the 35-page document the plan asks all agencies to work together, finally, on developing an enhanced educational opportunity for the chapter residents affected by mining and milling activities.

In an effort to fulfill that initiative, more than 10 agencies, Navajo and federal, showed up at the Mariano Lake Chapter in June to support the first of two summer outreach projects.

Affably titled Uranium 101, the workshop gave residents an understanding of uranium through science – what it is, where it’s found, how it behaves and when and why it is hazardous. It offered a foundation for understanding that will help local residents in affected chapters make well-informed choices when faced with decisions concerning uranium contamination in the future. The information also addressed behavioral changes that will reduce or eliminate exposure to contaminants, radon, and radiation, including understanding of pathways such as unregulated water sources used for livestock grazing that may affect the food they eat.

The complex workshop was presented in manageable increments by Angelita Denny, a physical scientist working in the U.S. DOE Office of Legacy Management. Each step in the curriculum she designed was followed by an explanation provided by a federally certified Navajo/English interpreter.

Although it has been offered at all the federal agency community meetings in the past, the need for a more central interpretation responsibility has grown over time as agencies learned that much of the information has no exact translation in the Navajo language. In many planning sessions held prior to the workshop Denny pressed for interpretive support of science facts. She explained to the federal and Navajo representatives that even very scholarly details, such as the release of energy and how alpha, beta and gamma rays travel through space would be welcomed information if interpreted properly.

During the workshop at Mariano Lake her explanations and PowerPoint visuals in English were followed by an often lengthy Navajo description.

Bess Tsosie expressed her appreciation. The interpretation at this meeting is culturally relevant and appropriate, she said during the question-and-answer period at the end of the day.

“In the past I found it difficult to understand exactly what ‘tailings’ is; but today when the interpreter explained it in traditional Navajo [using her hands to gesture the tail of something moving slightly down, with intermittent pauses, as if knotted] I finally understand. It was very fine cultural interpretation.”

Bess Tsosie addresses the many agencies that collaborated to present the Uranium 101 workshop. She said the interpretation was the highest quality. Photo by Sonja Horoshko.

Tsosie is president of Be’ekid Hóteelí Grass-root Organization, formed in 2011 to present the U.S. and and the Navajo EPAs with a list of demands, including recognition as the principal citizens group representing residents affected by the Gulf Mine, located at Mariano Lake Chapter. The group also demanded soil testing and investigation of earth cracks and open exploration holes as well as indoor radon testing.

Other commentators agreed with Tsosie, echoing a Navajo Nation statement included as an addenda in the 2014 Five Year Plan that “Diné know all things have within them the capability of both hozhooji (good or goodness) and hashkeji (bad or badness), and that both must be balanced to achieve beneficial results. This balance, known by the Navajo word hózhó, meaning harmony, is disrupted when natural laws are not observed. In Western science, this is known as a state of equilibrium, in which opposing forces balance each other and stability is attained and maintained.

“The Diné journey narratives speak of two Hero Twins that set about dealing with the Monsters. Navajo elders have taught that uranium, or leetsó, literally, ‘the dirt that is yellow’, is one of these Monsters — a powerful element that can disrupt hózhó when it is misused or disrespected. Certain substances in Mother Earth are not to be disturbed from their resting places, and the people now know that uranium is one such substance. Since leetsó has been disturbed by past mining and processing activities, Navajo natural laws charge the Diné with seeking ways to return leetsó to its natural balance with Mother Earth so that it does not further harm the sacred elements or the sacred balance of life.”

Shiprock disposal site

Simultaneously, the DOE Legacy Management team led by site manager Mark Kautsky is also planning two summer meetings. They are the next step in a concerted effort to teach residents about uranium science as it applies specifically to the Shiprock Disposal Site in northwestern New Mexico on the Navajo Nation. The meetings will be held Aug. 8 and Aug. 31 at the chapter house to discuss the deteriorating evaporation pond liner at the former uranium and vanadium ore processing facility, 28 miles west of Farmington, N.M.

Kerr McGee built the mill and operated the facility from 1954 until 1963. Vanadium Corporation of America purchased and operated it until it closed in 1968. The mill, ore storage area, ponds that contain spent liquids, and tailings piles occupied approximately 230 acres leased from the Navajo Nation.

In 1983 the U.S. DOE and the Navajo Nation entered into an agreement for site cleanup. By September 1986 all tailings and associated materials, including those contaminated from offsite properties, were encapsulated in a U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission-approved disposal cell built on top of the existing tailings piles.

A lined evaporation pond was built on the south side of the disposal cell. Water is pumped from horizontal wells on the north side of the cell from the floodplain alluvial aquifer between the San Juan River and the escarpment of the cell. The water from that and other nearby sources related to the disposal site around Shiprock is pumped out of the ground to the evaporation pond. It is, in a way, the interpreter explains, a method that enhances the power of Mother Nature — evaporation, natural solution.

Groundwater Compliance

The pond liner is 17 years old. Its estimated life span is 20 years. As the water evaporates and the water level decreases, small holes develop in the surface of the liner possibly from exposure to sunlight. Continual monitoring and repair of the holes is the responsibility of DOE Legacy Management. It is federally mandated to maintain the evaporation pond indefinitely to ensure that the selected groundwater compliance strategy protects human health and the environment.

As a practical response to the Uranium 101 Workshop, Legacy Management recognized that much of the printed material available to the public about the Shiprock site is difficult to understand. In an effort to increase the general understanding of the information they are also adopting the use of in-depth Navajo interpretation during the meetings to assure it is understood by everyone.

The group has indentified that the Shiprock residents’ understanding of the mill site and its presence in the community varies significantly. Basically, two groups’ needs will be addressed concurrently, making the dissemination of information a blend of history, site location, awareness and science. One group has first-hand occupational knowledge – a relative has become sick or passed away from exposure in the mill or a mine, or family contamination has occurred from construction materials or radon in the home, and /or they live downwind of a contaminated site. The group is generally older, and has lived in the chapter area for generations. They know the history of the disposal site and the mining extraction industry very well.

The other group is basically much younger. They have relocated there for many reasons, such as oil field employment, the Northern Navajo Indian Health Service Medical Center and access to a more convenient branch of Diné College. The result is a growing and prosperous community but also possibly less informed about the history site in the middle of town.

Unlike the workshop meetings, the Shiprock gatherings are intended to give the residents the necessary information that will help them understand the differences, risks and advantages of three options that may mitigate the hazard if deterioration of the evaporation pond liner becomes a reality.

The first, “No Action,” bears a misleading moniker. More correctly, it means no additional action will be taken and the current monitoring and maintenance will continue. Effectively, the option places the responsibility for any decision regarding the disposal cell in the future.

The second option is to replace the evaporation pond liner, meaning the uranium and other heavy metals settled in the bottom would be moved to facilitate replacing the liner.

Decommissioning the site is the third option. As under the second, contaminated waste would be disturbed. But in the decommissioning, the pond would be completely cleaned and all wastes moved to an off-reservation location. In both options the contaminated waste would be transported across Navajo Nation roads in order to deliver it to either a mill that re-processes waste or to another recognized disposal site off reservation.

But the Navajo Radioactive Materials Transportation Act of 2012 forbids the transport of uranium on roads inside the reservation. Many mining and milling proposals have gone before the Navajo Nation Council to affect changes that will open access to mining and transportation again, especially citing travel jurisdictions on state and federal highways that cross the Navajo land.

According to a DOE Legacy Management report of the May 2018 meeting at Cameron Chapter House in the Navajo Nation Western Agency Arizona, then-Navajo President Russell Begaye addressed the transportation of uranium, saying that although these routes run along federal and state highways, “Our sovereignty needs to be honored. If Navajo law says don’t transport uranium through Navajo lands that should be the final word.”

Collaboration

At the Mariano Lake meeting other agencies set up tables of helpful information because many people have difficulty translating and interpreting the tangled bureaucratic information. As an example the Navajo Birth Cohort Study, which tracks infants born to mothers living in areas where uranium was mined, milled or transported, was available to discuss their findings and also announce that their federal funding has been renewed. They are not going away.

There was information about the Superfund Research Program at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, and the Navajo Abandoned Mine Lands Reclamation projects. The Navajo EPA and U.S. EPA were there with information, beside the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, the BIA, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Representatives from the Indian Health Service handed out leaflets asking on the cover if you lived downwind of the Nevada Atomic test sites.

It was even possible to request a radon test kit for your home at the Mariano Lake meeting. That program has helped people replace contaminated homes on the reservation.

Although the audience was appreciative of all the interaction and collaboration, they were more influenced by the interpretation that was offered during the science workshop.

“I now ask you to provide this quality of interpretation at every meeting in the future,” added Tsosie at the end of the meeting. “I expect it,” she told the audience and the agency officials.

“The workshop was a success,” said Jamie Rayman, health educator and community involvement specialist with the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. “Mariano Lake Chapter hosted Navajo and U.S. government agencies to share the science of uranium; practical ways to reduce exposure and protect health; and what actions are being taken to address uranium in the area.”

The next Uranium 101 workshop will be held Wednesday, July 10, at Cove Chapter.