This view of McPhee Reservoir, taken looking west from House Creek on Oct. 19, shows the severity of the drought this year. Photo by Bill Hatcher.

“At first there was no water in the dry season and water for all domestic purposes was hauled from the river. They melted snow in winter.” — Ira S. Freeman, A History of Montezuma County.

When asked if he was concerned about being able to provide water to the residents of Cortez, Public Works Director Phil Johnson replied that he was “very concerned.” “Every year we do worry about the domestic water supply,” Johnson said.

Ken Curtis, general manager for the Dolores Water Conservancy District, agreed, telling the Four Corners Free Press he is worried about drought “all the time.”

Dry times

The fact that the Four Corners region is experiencing a sustained dry period is not a secret. Montezuma County has an average annual precipitation of 16 inches (Cortez averages 12.57, Durango 21, Mesa Verde 18.5, and Telluride 23.3), meaning that the region is “semi-arid,” defined by the USGS as receiving between 10 and 20 inches of precipitation per year. Less than 10 inches is an “arid” region.

Curtis said a lot of people are talking about the drought. “It’s rather intuitive if you live here and observe the dry forests, fire restrictions, dry grasses. Most of us in this area see the agriculture, see the mountains, and we all kind of know what’s going on,” he said.

The Dolores River flow was last recorded at 38 cubic feet per second on Oct. 28, before the recording station iced over the next day. This is about half of the 109-year average of 80 cfs for this date.

McPhee Reservoir’s current lake elevation was 6863.3 on Oct.27, with an active content of 18,801 acre-feet, which is the amount of water available for use.

Curtis said that “at 6855 we cut off the irrigation,” but explained that the reservoir has to maintain a ‘minimum pool’ to supply downriver fishery rights which are senior to the project water rights established in the 1980s.

Meanwhile, the Jackson Gulch reservoir is at 28 percent. Gary Kennedy, superintendent of the Mancos Water Conservancy District, told the Free Press that other local reservoirs “are all just as empty as we are.”

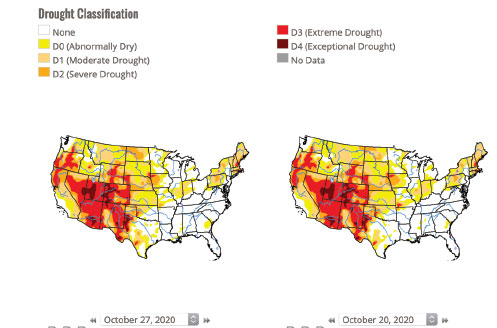

All the Four Corners states are experiencing some form of drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor website. As of Oct. 27, Montezuma County and the Four Corners are experiencing a sustained D4 condition – exceptional drought.

The Four Corners is in extreme or even exceptional drought in these maps

showing the classification as of the end of October.

The storm on Oct. 27 didn’t help much. Levels at all SNOTEL sites are low, including El Diente (16 percent), Lizard Head (15 percent), Lone Cone (30 percent), Sharkstooth, (NA),Mancos (4 percent) and Scotch Creek (9 percent) on Oct. 30. Percentages are the percentage of average.) SNOTEL sites are operated by the USDA National Resources Conservation Service.

A millennium drought

“We’re in a millennium drought – compared to droughts that happened hundreds of years ago,” Curtis said. “This year has been the worst 20 years in the 100-year records.” He told the Free Press that this year “is a lot like 2018. We had more water this year than 2013 and 2003,” but said we really won’t know the prospects for next year until March or April, depending upon the snowpack.

“It’s pretty bad, but we’ve seen other bad years in the last 20. I don’t know that this will be worse, but right now it doesn’t look great.”

What exactly is a drought, a “mega” drought, or a “millennium” drought?

Kyle Bocinsky, director of the Research Institute at the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center in Cortez, specializes in studying drought, climate change, and human adaptations to changing environmental conditions, and also serves as part of the Montana Drought and Climate project.

“Given what archaeologists know from tree rings and other records about the history of drought in the Four Corners, our region is in the midst of a historic mega drought,” Bocinsky said. “Starting in the year 2000, this mega drought is on the scale of those that contributed to the decline of the Chaco regional system in the mid-1100s and the great migrations of ancestral Pueblo people out of the Four Corners in the late 1200s.

“The summer of 2018 alone ranked as among the driest summers in the past thousand years — and current conditions in 2020/2021 appear to have beaten that record in portions of the region.”

Notably, the population of our region in the earlier periods Bocinsky refers to was about equal to the numbers of people living in the area today, Crow Canyon Executive Vice President Mark Varien told the Four Corners Free Press.

Droughts, second only to hurricanes in their potential for severe economic impacts, are grouped into four categories: meteorological, hydrological, agricultural and socio economic.

“A decrease in precipitation compared to the historical average for that area would qualify as a meteorological drought,” wrote Natalie Wolchover in a 2018 online Live Science article.

A drought that impacts the ability to produce crops – no matter how much or when the dry period occurs – is an agricultural drought, and a hydrological drought, often associated with meteorological drought, refers to persistent low volumes of water in rivers, streams and reservoirs.

Finally, a socioeconomic drought is when the demand for water exceeds the supply. Unfortunately, the Four Corners region is now experiencing the first three of these and consequently could be headed for socioeconomic drought.

The future for towns

What about the local municipalities?

Mancos, Cortez and Dolores each have their own established, senior water rights, but also use some water from the water companies. The Dolores Water Conservancy District supplies some water to Cortez, Dove Creek, and Towaoc. Cortez has a 2300-AF storage right from the DWCD, as well as a fairly senior surface right of 4.2 cfs from the Dolores River, according to Public Works Director Johnson.

Kennedy explained that Mancos has surface water rights on the Mancos river, as well as project water from Jackson Gulch reservoir, administered by Mancos Water Conservancy District.

The Town of Dolores owns and operates its own wells, as well as a treatment facility, and also has some senior rights on the Dolores river.

Since domestic water use is a priority, residents of each of these towns probably don’t have to worry about being shorted water, even during drought conditions. However, Johnson said that since we’re all tied to a single source of water – the snowpack – “there’s always a chance we could be in trouble.

“Our primary goal is that we have enough water for residents to consume,” he explained, and in case of a shortage we have to eliminate other uses. To that end, he is working with the city to establish a Drought Contingency Plan so that the ongoing drought will not have an impact on quality of life.

Both the City of Cortez and Town of Mancos have enacted water-conservation measures.

There are also “water docks” run by municipalities and water companies. These are water stations, located in Mancos, Cortez, Dolores, and Pleasant View, where customers can purchase water to fill cisterns. Costs vary, and users do not have to be residents of the county or municipality to buy the water.

When asked if he was concerned about people from out of the area coming in to use the water docks, Johnson said not at all. “People who haul water are the most conserving of water and are some of our best and most aware water users,” he explained. Many residents end up depending on the water docks because their property does not have any allocated water rights and there is no unappropriated water for them to apply for.

“Drought is a concern nobody has figured out a great way to fix,” said Curtis of DWCD. “We continue on under the current legal and contractual regime and do the best we can.”

He said in the case of a shortage, agricultural users are the ones who will be shorted. “It’s all coming from the snowpack that happens over the next six to seven months on the upper Dolores, and that’s the whole supply. Yes, there is an increased chance of shortage to the junior project users, with the agricultural and fish pools at most risk.”

Head in the clouds

What about cloud-seeding? Is it efficacious? Cloud-seeding is the process of applying

silver iodine during a storm so it rises into the clouds to create more snow by thickening the clouds to create condensation.

It’s been used in the area annually for the past 40 years from Telluride to Wolf Creek and the San Juan to the San Miguel rivers, as a collaborative effort of the state of Colorado, both the Telluride and Wolf Creek ski resorts, and local water companies including DWCD, MVIC, and the Southwestern Water Conservation District, which contract with Western Weather Consultants in Durango.

The seeding program starts on Nov. 1, but some years it’s not as viable as others, depending upon whether or not a storm is “seedable” according to the type of storm, temperature, and moisture levels.

“It certainly can be efficacious, but this is not to say it’s a formulaic activity,” Curtis told the Free Press.

“If you have the storm and are able to get the product nuclei into the clouds, it will increase the snow up to the 10 percent range, but it’s not just like you turn a switch and it magically increases the precipitation.”

Mayor Queenie Barz of Mancos emphasized this. “There’s no way to create additional water. The county can’t, the state can’t, the U.S. government can’t. We can’t make water – nobody can make water!”

No, humans can’t make water, but we can and do drastically alter the quality of the water as well as the environment it runs through.

Currently in an “exceptional drought” considered to be part of a “mega drought,” what are local citizens to do?

Hundreds of years ago, residents of this region adapted to ongoing drought cycles by reducing their population and migrating out of the area. These days, moving to another location may not be an option for most residents.

How can we adapt? While local citizens can conserve their domestic water use, and learn to use it wisely, our real concern is one of socioeconomic drought, since the biggest use of our water is agriculture. And in case of any water shortages, the irrigators will lose their water first.

Most likely we cannot continue to irrigate our semi-arid drylands in the manner we have become accustomed to over the past century.

If socioeconomic drought means there is not enough water to meet the demands, given our dwindling and over-allocated water supply in the face of current hydrological, meteorological and agricultural drought, adaptation means we have to learn how to change our demand.

Innovative agricultural strategies directed towards sustainable cultivation of both crops and livestock used to support local residents should be prioritized if we all want to continue living here.

How we decide to go forward remains to be determined, but based upon our local history and contemporary technologies, it’s certain that we humans do have the intelligence and gumption to overcome daunting obstacles.

Let’s hope that local residents are motivated to work together to provide life sustaining water for all.