Charges and countercharges flew through the air in the packed Montezuma County Commission meeting room the afternoon of July 14.

The county commissioners were accused of being power-hungry, of flouting state zoning regulations, and of hampering local economic development.

County Clerk Carol Tullis adjusts a microphone during a public hearing July 14 on proposed amendments to the Montezuma County Land-Use Code. About 90 citizens, some of whom were packed into the hall, came to the hearing. The amendments were adopted, with some modifications. Photo by Tom Vaughan/FeVa Fotos

On the other hand, those people criticizing the commissioners were labeled “socialists” and “gated community” elitists seeking to completely make over Montezuma County. They were likewise charged with hampering local economic development.

County-commissioner candidates, business owners, movers and shakers, an engineer or two, and ordinary citizens — around 90 people in all — were crammed into the stuffy room, overflowing into the hall and perching on the heater against one wall. Cell phones rang, people fidgeted and sweated, and speakers were shouted at to talk up.

Yes, it was another meeting on land use — a type of event that has become high theater in Montezuma County, stirring up more excitement than the opening of the latest “Batman” movie.

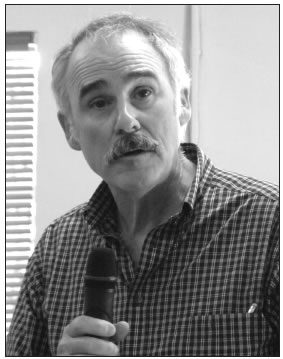

Kevin Cook of Dolores offers criticism of proposed amendments to the Montezuma County Land-Use Code at a public hearing July 14. Photo by Tom Vaughan/FeVa Fotos.

Some 30 citizens flocked to an evening meeting of the county planning commission on July 24 for a potentially explosive public hearing centering on an existing subdivision where the landowner wants to situate a 30,000-gallon propane tank.

When that hearing ended abruptly because of a ruling from the planningcommission chairman, however, the room rapidly emptied — though one man stayed long enough to ask the chair to explain what had just transpired, since he had been sitting next to the room’s noisy swamp cooler and could not hear a thing.

A dissenting voice

The July 14 hearing, however, which involved proposed amendments to the county land-use code, took the prize for drama as well as sheer length, lasting nearly seven hours.

When Roger Woody of Mancos, a critic of the proposed amendments, commented that he wished he were an attorney because “you wouldn’t get out of court for years,” Commissioner Steve Chappell sighed, “We won’t get out of this meeting for years.”

Six separate amendments had been proposed, most of which were not particularly controversial, and in the end, all were approved, with some modifications.

A decade ago, when the code was initially adopted, crowds that showed up for meetings on land use were largely opposed to zoning and regulations. Today, the audiences are usually in favor of more stringent planning rules.

When public comment began on the first proposed amendment on July 14, the prevailing mood among the crowd seemed to be suspicion and skepticism. Thus, when the county’s planning director, Susan Carver, said a letter had been received commenting on the proposed amendments and it would be put into the record, there were shouted demands to know what was in it.

Carver said she had three copies and offered to pass them among the crowd, but people, seeming to suspect a cover-up, began calling for the letter to be read aloud.

Chairman Gerald Koppenhafer warned that the letter was lengthy, but the audience was insistent, so he began reading the missive, which was from Miscelle Allison of Yellow Jacket, an advocate of private-property rights who represents a sizable contingent in the county.

“I reject this constant changing of the Montezuma County Land Use Code to accommodate a few that will not be pleased with the changes no matter how drastic and controlling the changes become,” Koppenhafer read from her letter.

“I have been told that our community is changing. Is this change occurring to adapt to the ‘new’ staunch socialists and self-proclaimed progressives moving into the area? . . . Now what I am to understand is government is attempting to replace freedom and chastise all citizens in the name of ‘sustainable development’ . . . [which] is geared around the active implementation of Agenda 21 as launched in Rio de Janeiro Brazil in 1992. . .”

At that point, someone shouted, “Never mind! We don’t need to hear the rest!”

Koppenhafer, however, did finish the letter, which ended with a call to “respect private property, no forced mandatory codes and continue to keep it a voluntary system.”

Illegal?

Allison’s sentiments were clearly in the minority at the hearing. The bulk of the speakers wanted more land-use planning and more control over uses on neighboring properties.

The most comments concerned the sixth and most controversial proposed change to the land-use code, the addition of a section on “Conditional Uses — Special Use Permit” that spelled out possible special uses that could be allowed in certain zones.

Sixteen special uses were listed, including commercial or industrial agribusiness, water or sewage systems, oil and gas drilling and production wells, pipelines and power lines, gravel mines, mobile asphalt plants, concrete batch plants, public or private lanfills, and waste-disposal sites. Special events such as concerts and motorcycle rallies were also listed, as well as retreats/guest ranches/conference centers.

The uses were broadly defined as including any or all of the following characteristics: “temporary or interim in use, created by nature, permitted by law or regulation, have a potentially greater impact than Uses by Right or are of unusual circumstance. . .”

The zones on which the special uses could take place were agricultural, ag business, or ag/residential, ranging in size from A/R 10-34 (acres) to A-80. Land classified as unzoned was also included.

The idea behind the amendment, county officials said, was to allow certain temporary activities to occur through the obtaining of a permit, without making the landowner rezone his land commercial or industrial.

However, critics saw the proposal as a way to put more power into the hands of the county commissioners, enabling them to allow all sorts of possibly undesirable uses on ag land.

Chuck McAfee of Lewis, who successfully pursued a lawsuit against the county over a proposed gravel pit near his property, presented a letter from his attorney, Jeffery Robbins of Durango, that called the proposed amendments “contrary to good planning, contrary to recent appellate cases and illegal on their face.”

The letter stated, “The proposed changes would allow for any and all land uses, be they commercial, industrial, gravel mining, asphalt plants, etc., in any and all zones within the County irrespective of the underlying zoning protections. . .”

It said the amendments would constitute “spot zoning,” which is illegal under state law.

“I really feel that if you adopt this, you have taken predictability and thrown it completely out the window,” McAfee told the board.

But Bob Riggert, chairman of the planning commission, which helped develop the amendments along with the planning department, defended the proposal. He said the planning board had examined regulations in 13 other counties in Colorado and found that all allow for some conditional or special uses on agricultural land.

Among those counties is Archuleta, which allows oil and gas operations, resource extraction, power lines, sewage and water systems and sanitary landfills on ag land through conditional- use permits; and San Miguel, which allows oil and gas operations, mineral exploration, utility lines, solid-waste disposal and communication facilities through administrative review or special- use permits.

“It is commonplace that there are interim alternate uses that are available,” Riggert said. “Is it in the best interest of the county to zone property commercial for interim or temporary uses? Once the zoning is in place it is difficult to return the property to agriculture.”

McAfee countered that such statements showed that the underlying assumption was that the special uses would be allowed, one way or another.

“The comments. . . indicate that the use will be okayed, either by highimpact permit or zoning,” McAfee said. “Never is there an underlying thought that maybe it just isn’t going to be there.”

Pros and cons

A concern about lack of control over neighboring uses was prevalent among the speakers, many of whom said the amendment would put too much power into the hands of the commissioners.

“We need predictability,” said Mary O’Brien of Mancos, adding that someone buying into an agricultural area wants to know it will remain agricultural.

Rich Lee, who lives near Dolores off Highway 491, said he had “buyer’s remorse” after buying his tract in a subdivision and finding out that a propane-gas depot had been proposed in the same subdivision (the proposal that was to have been discussed at the July 24 planning-commission meeting).

“I know you have trouble trying to balance the good-old-boy days of the ’50s with us socialist Nazis coming in,” he told the commissioners.

Some charged that a lack of planning and strict zoning is hampering economic development.

“I think one of the reasons we have problems in this area attracting . . . investment is because we don’t have that sense of certainty,” said Bill Teetzel of CR 34.5. “We need to be able to plan ahead and not just live in a state of anarchy.”

Mike Matheson of Sky Ute Land and Gravel said he had proposals he wouldn’t bring to the table now because “the process is balled up.”

“I agree there needs to be good definitions and a good understanding of what the process is,” he said.

Others criticized specific language in the amendment, saying that a “temporary” use needed to be defined.

“The sun that shines in the sky is temporary,” Woody said. “It’s going to wink out of existence some day.”

“Rather than offer more flexibility in the code, I think we need to be more definitive,” said Jerry Giacomo of Dolores.

But Koppenhafer argued that a gravel pit is temporary, compared to residential development.

“My personal opinion is I’d rather see that gravel pit there than a whole bunch of houses, because that gravel pit will go away,” he said. “They’ll reclaim that and it will go away.”

A few of the public comments were in favor of the amendment as proposed.

“Montezuma County is not a gated retirement community,” said Dexter Gill of Lewis. “It is a place where people still need to work to make a living. . . We must be able to take advantage of every business opportunity we have.” He said the county receives far more property-tax revenues from natural- resource extraction than from residential properties.

Joyce Humiston of Mancos also favored the amendment, saying people who don’t want landfills should “quit making trash” and that people who oppose gravel pits drive on roads made with gravel.

“I know you don’t want it in your backyard, but it’s going to go in someone’s backyard,” Humiston said.

Some deletions

The inclusion of “public or private landfills” on the list of special uses worried several of those who spoke. McAfee questioned how they could be considered temporary. “If you decide to quit using a landfill and to move it somewhere else, what are you going to do? Dig it all up?” he asked.

“There is nothing interim about a landfill,” agreed Dian Law of Mancos. “We are going to be long gone — I mean as a species — before those landfills are done.”

People were also concerned about “waste disposal sites” as a special use.

Civil and environmental engineer Nathan Barton of Cortez, who supported the amendment, explained that landfills could be small ones for burying construction-demolition debris or old road base and culverts left after road improvements. Waste-disposal sites, he said, could be for disposing of agricultural waste residue or sewage sludge.

However, when the commissioners eventually adopted the amendment, they removed landfills and waste-disposal sites from the list, sending those issues back to the planning commission for clarification.

They also deleted conference centers from the list, saying those were too large to be considered a special use. And they added the phrase “to date certain” to mobile asphalt plants and concrete batch plants, meaning that those uses would have an end date.

Correcting the code

Despite the opposition, the commissioners did adopt all the proposed

amendments as modified, voting 3-0. Before the vote, Chappell asked the planning commission’s Riggert whether he believed the land-use code should be scrapped entirely, or merely amended.

Riggert said, although the code has “some immediate weaknesses,” the planning commission had discussed the amendments at length and felt good about them. “I don’t feel it would be spot zoning,” he added.

Commissioner Larrie Rule, who is up for re-election this year and faces a primary opponent in fellow Republican Danny Wilkin, said he has to consider the views of the whole county. “There’s a lot of people who are not here today, and we have to listen to those people too,” he said.

He added that he found it ironic that the commissioners have been criticized for not always following the recommendations of the planning commission, but that now they were being criticized for wanting to follow the planning board’s suggestions.

Rule also said he strongly disagreed with accusations that the commissioners constitute a “good old boy” board. He pointed out that they had hired a new sheriff and new county administrator from outside the county, and that their new road supervisor has worked many other places as well.

“To me these are not good-old-boy decisions,” he said.

Koppenhafer said there had been a lot of misunderstanding over the commissioners’ intent in considering the amendments.

“I don’t think any one of us wants to do anything to hurt this county,” he said. “But I also think we need the ability to do some things to help this county.”

He said he had a real problem with people who try to limit growth and say, “I don’t want anything next to me.”

“If we’d had the same attitude a lot of you sitting here have, we would have kept you out,” he told the crowd.

Koppenhafer said the amendment on conditional uses and special-use permits was necessary because of two rulings by the Colorado Court of Appeals, one involving the gravel pit near McAfee and the other concerring a warehouse expansion near Mancos.

In both cases, the court ruled against the county, criticizing the commissioners for granting highimpact permits to those uses and saying their actions violated the land-use code as written.

Koppenhafer said the new language was needed so activities such as gravelmining, oil- and gas-drilling and pipeline construction could occur legally on agricultural land without the whole parcel having to be rezoned as commercial or agricultural. It does not grant the commissioners broad powers, it specifies and narrows the scope of high-impact permits, he said.

Commission attorney Bob Slough agreed. Under the old language, the high-impact permit process was “wide open,” he said, with conditional uses being defined as anything with a valid high-impact permit.

“The board is not ever going to have the discretion it has exercised for the past 10 years,” Slough said.

The appeals-court ruled that, under the code as it was then, only agriculture and agribusiness could be allowed on ag lands.

“In the current situation, you can’t get a gravel pit next to you, but you can sure get a slaughterhouse next to you,” Slough said. (A slaughterhouse is considered an “agribusiness.”) “Does that make any sense?”

The amendment was a good-faith effort intended to “correct the code so it complies with the appellate-court ruling,” Slough said.

“I’ve said it over and over and over, if you’re going to have zoning, zoning is supposed to mean something,” he added.

The commissioners formally adopted the modified land-use amendments on July 21 — 10 years and one day after the original county land-use code was approved.