Part II of a two-part series

Read Part I

From left, David Casey, supervisory forester with the Dolores Ranger District, Jackie Rabb, and Robert Meyer, chair of the Mancos Trails group, are on a tour in the Chicken Creek area near Mancos on April 25. This is an untreated area. Meyer is leaning on a stump cut in the 1920s wIth a two-man crosscut saw, which leaves high stumps. Photo by Janneli F. Miller

Sometimes in life we have to engage in unwelcome short-term behavior in order to get long-term results. To lose weight, for instance, we may have to give up desserts or big Mac’s for a time.

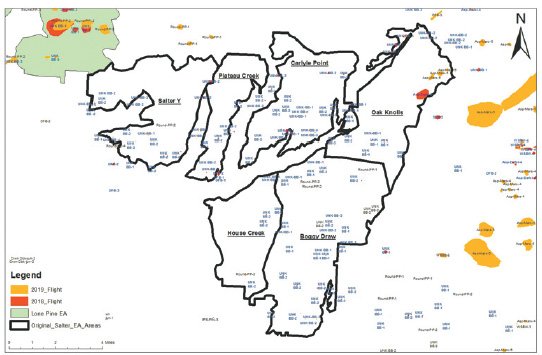

That sort of decision is being considered in regards to the Salter Y Vegetation Management Project in the Dolores District of the San Juan National Forest.

The question is whether proposed short-term treatments, which include commercial logging and some prescribed burning, will provide long-term benefits that will outweigh the impacts of the treatments on recreation and the environment.

“The current need for mitigation on the Salter Y area is really due to the public,” noted Jen Stark, Dolores Town trustee, after attending a tour of an area near Mancos called Chicken Creek. The tour of a previously treated forest site was sponsored by the Dolores Watershed Resilient Forest Collaborative (DWRF) on April 25 to help the public understand the possible impacts of the Salter Y Vegetation Management project.

The project, which is expected to last about 10 years, will take place on 22,346 acres of national forest northwest of Dolores, including the popular Boggy Draw area.

Stark explained that “public pressure on political spheres and government policy generated a long-term fire-suppression strategy.” Historic extractive activities such as timber harvesting and cattle grazing combined with current drought conditions have had deleterious impacts on local forest health.

According to Danny Margolis, DWRF coordinator, “We want to facilitate focused practical and meaningful dialogue about the project. The framing of the project is very much in line with the goals and mission of DWRF.”

The Salter Y project is aimed at improving forest health, but it will change the forest experience for users while it is taking place.

The draft environmental assessment prepared by David Casey, supervisory forester for the Dolores Ranger District, explains that the purpose and need for the project is threefold:

- to improve resilience and resistance to epidemic insect and disease outbreaks;

- to increase the structural diversity of the ponderosa pine forest represented across the landscape

- to provide economic support to local communities by providing timber products to local industries in a sustainable manner.

The draft EA proposes three alternatives: no action; the modified proposed action; and a large-tree-retention alternative that limits harvesting to trees 20 inches or less in diameter at breast height (dbh).

Forest officials acknowledge that the project will have significant impacts on recreation, wildlife, vegetation, watersheds, soils, scenery and transportation. The reasoning is that these impacts will be far less damaging to the forest than the impacts of major wildfires, insect infestation and overall declining forest health if nothing were done.

The area targeted for treatment is in the wildland-urban interface (WUI), the transition between unoccupied land and human development. If left untreated the area in question could potentially be subject to destructive crown fires, according to the draft EA.

The areas designated for treatment in this project are neither resilient nor diverse. There are very few large trees, many dense stands of same-age, same-size trees, and a significant amount of brushy oak undergrowth.

This forest structure inhibits seedling production and regeneration, since trees in tight clusters compete for water and sunlight and may become stressed. Stressed trees are susceptible to insect infestations or parasitic growth such as mistletoe, and are less likely to resist fire.

According to forest officials, removing weak trees and brushy overgrowth through tree-cutting, tree planting and prescribed fire improves the ability of the remaining trees to become healthier, produce seedlings and resist fire. More frequent, low-intensity fires are easier to manage and incur less damage.

In addition to the draft EA, a 73-page biological evaluation describes direct and indirect impacts of all three alternatives to sensitive animal species such as the boreal toad, northern leopard frog, flannelmouth sucker, flammulated owl, Lewis’ woodpecker, and northern goshawk.

It addresses pollinators including Monarch butterflies, the Western bumblebee, and several species of bats.

Species of special interest are Abert’s squirrel, mule deer and elk, the hairy woodpecker and some other bird species.

Many of the environmental impacts in both the draft EA as well as the biological evaluation are listed as “Finding of No Significant Impact,” meaning the treatment activities will not really impact the forest.

But some environmentalists disagree.

Jimbo Buickerood, lands and forest protection program manager for the nonprofit San Juan Citizens Alliance, submitted comments saying, “We find the determination of a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) to be invalid being the EA provides insufficient information on which to make that finding.”

Matt Sturdevant, district wildlife manager for Colorado Parks and Wildlife, acknowledges that there are a wide range of species in the proposed project area.

“The project area provides habitat for a multitude of wildlife species including elk, mule deer, black bear, mountain lion, coyote, fox, bobcat, and Merriam’s turkey, dusky grouse, Cooper’s hawk, red-tailed hawk, sharp-shinned hawk, northern goshawk and many other species,” he wrote. “The area contains valuable fawning and calving grounds for deer and elk, as well as critical winter range for these same species.”

CPW said it supports the project because it will improve forest health. “We recognize that short term impacts to wildlife may occur from the construction and use of roads, as well as the mechanical and human disturbance during vegetation thinning. However, we believe that the improved wildlife habitat offsets these impacts in the long run.”

‘Need to be patient’

The Dolores Ranger District is considering 123 public comments it received during the comment period, which ended in March. District Ranger Derek Padilla explained that if comments fall within the prescription of the draft EA there will be no need to write a new EA and the project will proceed.

Citizens in support of the project expressed an understanding that short-term disruptions to recreation, including camping, mountain-biking, hiking and hunting in the area, are undesirable but necessary.

“The intention behind this project is a good one. In order to promote forest health and resiliency, many of us will need to be patient with closures, noise, traffic, changes in aesthetics, etc.,” wrote Robin Richard, local resident of 17 years.

But some people think otherwise.

“Although I understand the purpose of this project, I oppose it due to the fact this is a high use recreational area. The noise and pollution of the large trucks, as well as the falling timber would greatly affect the safety as well as the recreational experience,” wrote Gretchen Schmeisser.

The draft EA admits that economic impacts are unknown, but the project is expected to boost local timber operations, one of its stated goals. It is uncertain whether logging’s benefits would outweigh the benefits of the burgeoning recreation industry.

The most frequent concern expressed in public comments was the disruption to recreational activities and the recreation economy. Other concerns were the lack of specific economic information, and the treatment activities and scope of the project.

Some commenters asked for retention of large trees and adaptive forest management strategies. Some expressed safety concerns, especially regarding the primary access road to the project, County Road 31.

“My number one concern is the paved road that leaves Dolores on the way to the Boggy Draw area and the Salter area. This road is already excessively traveled and not well maintained. This creates a hazard for the users of the road no matter what purpose,” wrote Mike Hill.

Seven environmental organizations (including SJCA, Center for Biological Diversity, and Defenders of Wildlife) urged the SJNF to adopt Alternative 3, which leaves larger trees standing (no harvesting of trees over 20 inches dbh).

Wildfire potential

The availability of companies to do some commercial logging is key to the project.

The thinking is that since there is now timber industry in place, tree cutting can take place in a swifter and more economical manner than when the Forest Service cuts and then sells the harvested trees.

Casey told the group on the DWRF tour that he can “sell right off the tree,” eliminating the need for decking and huge timber piles, which means less disruption to forest areas and a quicker treatment time.

The Montezuma County commissioners supported Alternative 2 in comments.

“We realize that there will impacts to all of the resources in the project area and that some of them will be negative for a short time,” they wrote. “However the long term benefits to all resources will out-weigh the short term inconveniences.”

While the project may impact recreation, they wrote, “The potential for catastrophic wildfire far outweighs the possible economic loss from recreation due to treatment. . . . We agree that we are trying to achieve a healthy, resilient forest that is resistant to disease, insect and wildfire outbreaks. However that does not mean that we envision some sort hands-off pre-Columbian forest condition.”

Dolores’s mayor and trustees also support Alternative 2, but voiced concerns. “There is not adequate language in the Draft EA addressing the negative economic impact due to the temporary loss of recreational opportunities,” they wrote.

They especially focused on impacts to hunting, stating that since big-game numbers are declining in the Salter Y area, it was “imperative” the project not further impact big game.

The local economy

But it is not only hunters who provide economic benefits to Dolores.

Mark Youngquist, owner of the popular Dolores River Brewery in operation for 19 years, also noted potential economic impacts.

“There appears to be little mention of the possible economic impacts of trail closures both temporary and long term on the local businesses other than logging, as well as the impacts on the attractiveness of the vistas and intimacy of the camping experiences available in the Boggy Draw area,” he wrote.

Peter Eschallier, owner of Cortez’s Kokopelli Bike and Boards, which is opening a new store in Dolores, did not mince words in expressing his opposition: “I am concerned that this project would impact the Boggy Draw trail system negatively, reducing the number of mountain bikers that visit and use this area. We are committed to investing in our sustainable outdoor industry. . . Any interruption and negative impact to these trails would be disastrous to our business.”

Kokopelli co-owner Scott Darling agreed, writing, “This proposed logging could not come at a worse time. The trail expansion that was just finished may be altered, negating countless volunteer hours of work.”

Dolores’ interim town manager, Ken Charles told the Free Press, “There’s no doubt that the recreation industry will be impacted,” but said the town was not taking a position.

The town encouraged the SJNF to work with the Southwest Colorado Cycling Association on trail closures, detour routing and signage, and public education measures.

SWCCA is a local nonprofit committed to enhancing the mountain-bike experience by building and maintaining local trails, including those in Boggy Draw. They also host and sponsor local races including the upcoming 12 Hours of Mesa Verde, to be held May 8.

Dani Gregory of SWCCA included three pages of recommendations in her comments. “This project will result in temporary trail closures which will hurt local businesses, anger users and deter visitors,” she wrote.

SWCCA recently constructed 24.4 miles of trails in the Boggy Draw system.

Gregory said “there is not adequate language in the EA addressing the negative economic impacts due to the temporary loss of recreational opportunities.”

Approximately one-quarter of those commenting recommended following the suggestions of SWCCA or mitigating impacts on trails.

Other specific concerns mentioned by Dolores town officials included the impacts to residents on 11th Street, which turns into CR 31. The town wants to have a designated truck route, to limit commercial traffic on 11th Street from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m., and to ensure that contractors are aware that the in-town speed limit of 15 mph on 11th Street will be enforced.

This was mentioned by several people.

“The movement of heavy equipment to and from the proposed project areas requires that oversize machines and vehicles travel on local paved and unpaved county roads,” wrote Shaine Gans, who lives near Boggy Draw. “This poses an unnecessary danger to residents. . .”

In addition, Dolores officials wanted more information on potential impacts to water quality, and suggested that the Forest Service address effects to fisheries, erosion control, or possible spills.

But the Dolores Water Conservancy District said the project would help protect water quality in the long term.

Mike Preston, former general manager of the DWCD, commented that the project “will avoid damage and disruption to water supplies by lowering the risk of catastrophic wildfire and the damage done by toxic runoff into the Dolores River from fire scars. These vegetation treatments will contribute to the availability and quality of Dolores River water flowing into McPhee Reservoir.”

Preston continued, “Areas that have received mechanical and prescribed fire treatments offer improved recreation and hunting opportunities coupled with significant reduction in wildfire risks. The benefits that proposed treatments will have on water quality and availability are of profound interest to everyone that relies upon McPhee reservoir as their water source.” Forest products What about local logging companies and foresters?

The two timber companies mentioned by the Dolores District’s Padilla and Casey during the DWRF tour were Montrose Forest Products and the Ironwood group. The Ironwood facility, located on County Road T outside Dolores, was established in 2019, when owners from Oregon purchased and refurbished the old Montezuma County plywood plant. The company produces wood pellets and plywood veneer.

Montrose Forest Products, LLC, which is owned by Neiman Enterprises out of Wyoming, uses beetle-killed ponderosa pine to manufacture studs, timbers and various shop grades cuts, pine boards, pattern, decking, and industrial, or shop, lumber.

Tim Kyllo, resource forester for Montrose Forest Products, wrote that “our 95 direct employees at the mill and approximately 120 people that make up our independent logging and trucking contractors are extremely supportive of any effort the San Juan National Forest makes to provide commercial timber for bid.” Timber products extracted from the Salter Y project area would be transported and marketed out of the area.

Kyllo’s comments focus on lessening restrictions on logging in the proposed Salter Y project area. “We strongly urge the SJNF to not limit the construction of temporary road construction to access planned timber sale units,” stating that the landscape conditions require “the absolute need for purchasers to be able to build temporary road locations on pre-approved USFS locations as necessary to economically log and haul the timber to mill sites. This must be incorporated into the final decision without restrictions.”

Molly Pitts, Colorado programs manager for the Intermountain Forest Association out of Salida, commented, “Given that several of IFA’s members heavily rely on timber output from the San Juan National Forest and have made substantial investments to help facilitate treatments, we are excited about the proposed Salter Vegetation Management project on the Dolores District.” She agrees with the need to increase age class and structural diversity in the forest and supports Alternative 2.

“We feel strongly that Alternative 3, with a diameter cap of 20 inches, will not achieve the desired goals and objectives and will put stands at risk from insects and disease and catastrophic wildfire. Furthermore, it will limit flexibility in creating the necessary habitat for wildlife.”

But some comments by retired foresters or citizens with backgrounds in forestry were highly critical of the proposed project.

Harold Ragland, of Ragland and Sons Logging and Stonertop Lumber, has 53 years of experience working in the forest. He believes that “logging and recreation can operate in a complementary fashion.” His primary concern is with controlled burns, which he feels are a “complete disaster.” Fire damage turns a piece of wood that could possibly could be used as valuable molding to dunnage which is nearly worthless, he said, and controlled burns decrease the value of the public’s timber by up to 100 times. He also said controlled burns do “cruel and inhumane damage” to wildlife.

William Baker of the University of Wyoming stated, “Reasons given for preferring Alternative 2 over Alternative 3 are not valid. . . . It is well documented that in ponderosa pine forests it is these large, old trees that provide the essential resistance and resilience to fire that is now particularly needed as fire is increasing with global warming. Large trees have the thickest bark, the highest crown base height, and have the greatest ability to survive substantial crown scorching and still resprout and survive. It is thus essential for the Final EA, if the goal is to include increased resistance and resilience to fire, to heed and remedy the serious deficiency in large trees as an essential part of the desired conditions for the project area.” Another critic, Dick Artley, a forester, submitted 21 pages of comments. “Never before have I heard of such ham-handed mismanagement of the precious land owned by 332 million Americans,” he wrote.

Artley voiced concern about the proposed use of glyphosate on noxious weeds. He is concerned about the use of fire and logging to prevent forest fires. He said fire-prevention measures should instead focus on reducing the flammability of houses, planning evacuation routes, burying power lines, and zoning to reduce growth into WUI areas.

Public comments objecting to the project, or urging the Forest Service to mitigate impacts on recreation by preserving the trail system at Boggy Draw, ran about 3 to 1.

Buickerood told the Free Press the draft EA was one of the weakest he had seen, containing little economic information. “I’m afraid that the economic piece is too tilted towards forest industry,” he said. “Frankly it seems to be giving industry some contracts, and they’ll make more money on the big trees.” He is also concerned about exactly where the economic benefits from logging will go. “It very well might be that most of that financial gain will go out of the area, if they are mostly purchased by Montrose.”

Buickerood said, “I think you can restore the forest and provide some economic benefit in the same time. There is short-term disruption, but can we figure out a way to minimize that? It would include cutting back on the number of days harvest is going on and the number of areas that are open at one time, and not roll over all the work that has been done.” Sam Bagge, who grew up biking these trails and has a degree in environmental and sustainability studies, wrote that “the methods being proposed are detrimental to the ecosystem and biking community. There are less invasive management tactics that can be employed. While they will most likely be more costly and timely they are necessary to preserve the unique trail system and the ecosystem it is in.”

Gail Binkly contributed to this article.

Here’s what I noticed on my trip home from the grocery store the other day:

Here’s what I noticed on my trip home from the grocery store the other day:

It began as a nifty idea for Orion Magazine in late March of 2020 as the nation entered the first wave of stay-at-home orders in response to the growing pandemic. “Every week under lockdown, we eavesdrop on curious pairs of authors, scientists, and artists, listening in on their emails, texts, and phone calls as they redefine their relationships from afar,” described the introduction for the series, dubbed “Together Apart.”

It began as a nifty idea for Orion Magazine in late March of 2020 as the nation entered the first wave of stay-at-home orders in response to the growing pandemic. “Every week under lockdown, we eavesdrop on curious pairs of authors, scientists, and artists, listening in on their emails, texts, and phone calls as they redefine their relationships from afar,” described the introduction for the series, dubbed “Together Apart.”

It’s been written that the outlaw known as Billy the Kid was born Henry McCarty in New York City in 1859. Or maybe his real name was William H. Bonney, or William Wright, or Joseph Antrim. He moved with his family to Kansas in 1870, then to Santa Fe, and finally to Silver City, where his mother died in 1874, setting Billy, age 15, on a path of petty theft and cattle rustling. Or perhaps he was just a rowdy cowhand falsely accused of stealing horses. One thing for certain is that young Billy, following the murder of New Mexico Territory rancher John Turnstall in 1878, cast his lot with a group of Turnstall avengers known as the Lincoln County Regulators who took up arms in opposition to the “Santa Fe Ring” of corrupt power brokers fronted by local businessman James Dolan. The resulting conflict would soon escalate into the notorious Lincoln County War of 1878-81.

It’s been written that the outlaw known as Billy the Kid was born Henry McCarty in New York City in 1859. Or maybe his real name was William H. Bonney, or William Wright, or Joseph Antrim. He moved with his family to Kansas in 1870, then to Santa Fe, and finally to Silver City, where his mother died in 1874, setting Billy, age 15, on a path of petty theft and cattle rustling. Or perhaps he was just a rowdy cowhand falsely accused of stealing horses. One thing for certain is that young Billy, following the murder of New Mexico Territory rancher John Turnstall in 1878, cast his lot with a group of Turnstall avengers known as the Lincoln County Regulators who took up arms in opposition to the “Santa Fe Ring” of corrupt power brokers fronted by local businessman James Dolan. The resulting conflict would soon escalate into the notorious Lincoln County War of 1878-81.

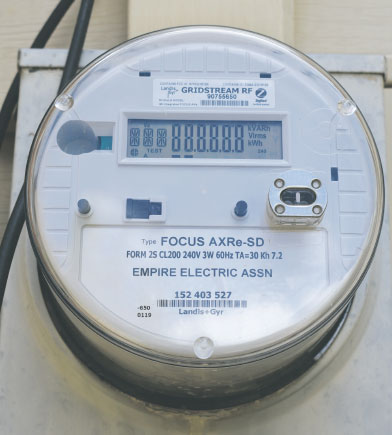

In an interview, Andy Carter answers basic questions about the coming change

In an interview, Andy Carter answers basic questions about the coming change